Successful treatment of acute respiratory failure in a patient with pulmonary Mycobacterium abscessus infection accompanied by organizing pneumonia

Introduction

Organizing pneumonia (OP) is an inflammatory lung disease characterized by proliferation of granulation tissue in the respiratory bronchioles, alveolar duct, and alveoli with or without obliteration of distal bronchioles. In addition to the idiopathic form (cryptogenic OP), it can develop secondarily for many reasons, such as infections (including mainly bacteria and viruses), connective tissue disease, hematological disorders, malignancies, use of certain drugs, and radiation therapy (1). A number of viral and bacterial organisms, including herpes virus, coronavirus (especially severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus; SARS-CoV) infection, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis have been identified as infectious causes of OP (2-5). However, Mycobacterium abscessus (M. abscessus) has rarely been reported as a causative factor of OP with acute respiratory failure (ARF) (6). Here, we report a woman diagnosed with ARF due to pulmonary M. abscessus infection with simultaneous presentation of OP.

Case presentation

A 67-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital with shortness of breath and fever that had begun 1 week earlier. She had a previous history of diabetes mellitus and degenerative arthritis.

On admission, her vital signs included blood pressure of 85/59 mmHg, body temperature of 38.3 °C, heart rate of 127 beats/min, and respiratory rate of 30 breaths/min. Chest auscultation revealed crackles in the right middle and lower lung fields. Arterial blood gas analysis (ABGA) showed pH 7.42, pCO2 31.7 mmHg, PaO2 69.4 mmHg, HCO3 20.5 mmol/L, and SpO2 92% on oxygen supplied via nasal prong at a flow rate of 4 L/min. A complete blood count results were as follows: leukocytes, 11,170/mm3 (segmented neutrophils, 84.9%; lymphocytes, 11.2%); hemoglobin 9.5 g/dL; hematocrit, 27.6%; and platelets, 246,000/mm3. Blood chemistry was as follows: blood urea nitrogen (BUN), 10.1 mg/dL; creatinine, 0.42 mg/dL; aspartate transaminase, 86 U/L; alanine transaminase, 23 U/L; total bilirubin, 0.34 mg/dL; lactate dehydrogenase, 448 U/L; creatine phosphokinase, 28 U/L; C-reactive protein, 6.67 mg/dL; and procalcitonin, 0.97 ng/mL. The prothrombin time (PT), international normalized ratio (INR), and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) were 11.8 s, 0.98, and 28.4 s, respectively.

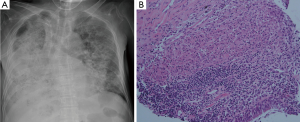

A chest radiography revealed mass-like consolidation in the right mid to lower lung zone and ill-defined patchy consolidation in the left lower lung zone (Figure 1A). Chest computed tomography (CT) revealed ill-defined multifocal consolidations with bronchial wall thickening and air-bronchogram in both lungs, particularly on the right middle lobe, right lower lobe and left lower lobe (Figure 1B,C).

Empirical intravenous antibiotic therapy was initiated with piperacillin/tazobactam and levofloxacin. An initial sputum culture was negative, as was sputum acid-fast bacilli (AFB) smear. On the third hospital day, her general condition and hypoxia deteriorated on a facial mask with an oxygen flow rate of 8 L/min and sustained fever was observed. She was transferred to the intensive care unit and a high flow nasal cannula was applied. Antibiotics were switched to meropenem and vancomycin. Flexible bronchoscopy for microbial evaluation showed no apparent endobronchial lesions. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) performed in the right middle lobe revealed a white blood cell count of 2,457/mm3 (segmented neutrophils, 68%; lymphocytes, 27%; other cells, 5%), red blood cell count of 378/mm3, CD4/CD8 ratio of 0.8, no bacteria, viruses, or fungi, and negative AFB smear. All virus PCR and microbial tests, including blood and urine cultures, were negative.

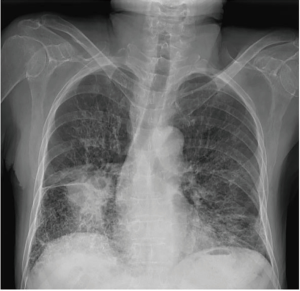

On the 7th hospital day, her chest radiography was more aggravated (Figure 2A), and percutaneous needle biopsy (PCNB) was performed for right middle lobe lesion. The PCNB specimen showed OP with non-necrotizing epithelioid cell granuloma (Figure 2B). Prednisolone (1 mg/kg/day) was administered, and dramatic improvements of hypoxia and shadows were seen. On the 12th hospital day, culture-positive (liquid culture media) for nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) was noted in her BAL fluid and sputum AFB. Finally, M. abscessus was reported on the 25th hospital day. A drug susceptibility test revealed that the isolate was susceptible to clarithromycin [minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), ≤0.5 µg/mL], and showed intermediate susceptibility to amikacin and cefoxitin (MIC ≤32 µg/mL, both). The empirical antibiotic therapy was stopped, and she was started on intravenous amikacin, cefoxitin, and oral azithromycin. After 8 weeks of the anti-mycobacterial therapy with prednisolone, improvement was detected on clinical findings, laboratory tests, and radiologic images (Figure 3). She was discharged on hospital day 60 with a recommendation to continue oral azithromycin, and to taper the prednisolone dose over 6 months.

Discussion

The NTM are ubiquitous environmental organisms that typically cause disease in patients with altered host defenses (7). Pulmonary NTM disease is the most common type of involvement and occurs primarily in patients with preexisting structural lung damage such as emphysema or bronchiectasis. The clinical features of NTM lung disease in immunocompetent patients include fibrocavitary disease, nodular/bronchiectatic disease, solitary pulmonary nodules, and hot tub lung (7).

On the other hand, rare cases with different disease entities have been reported: NTM disease accompanied by histologically proven OP in which patients developed acute or subacute symptoms with infiltrates on chest images, and improved rapidly following treatment with a combination of a corticosteroid and anti-mycobacterial therapy (6,8-10). Hamada et al. (8) reported a 67-year-old woman with fever and dyspnea; her sputum culture confirmed Mycobacterium intracellulare, and transbronchial lung biopsy (TBLB) revealed OP that showed dramatic clinical improvement clinically with corticosteroid and anti-mycobacterial treatment (clarithromycin, rifampicin, and levofloxacin). Jones et al. (9) reported a 58-year-old woman with Mycobacterium avium (M. avium) complex infection, and Starobin et al. (10) described an 85-year-old woman with Mycobacterium kansasii infection with biopsy-proven OP; both cases were successfully treated with anti-mycobacterial treatment (rifampicin, ethambutol and isoniazid, ethambutol, rifampin, respectively) and corticosteroids. In these reports, the authors considered that OP was probably induced secondary to NTM disease or that OP was one of the clinicopathological features of NTM lung diseases. Nakahara et al. (6) reported five patients with NTM lung disease and the coexistence of OP; four patients had M. avium infection and one patient had M. abscessus infection. These reports described NTM lung disease accompanied by OP that improved with corticosteroids and anti-mycobacterial treatment.

In the present case, the CD4/CD8 ratio of BAL fluid lymphocytes was 0.8 and the lung biopsy specimen was consistent with OP. Pulmonary lesions, as well as respiratory symptoms, improved rapidly in response to corticosteroid. Hence, the clinical manifestation was prominent OP that induced ARF. Another consideration was a hot tub lung that in an uncommon presentation of NTM lung disease. Hot tub lung as a hypersensitivity-like disease is similar to hypersensitivity pneumonitis with respect to its clinical and radiological presentation. The typical chest CT findings of hot tub lung are centrilobular nodules and/or ground-glass opacities (7,11,12), which are largely different from the infiltrating consolidation with air bronchogram seen in the present case. The CD4/CD8 ratio in the BAL fluid of hot tub lung patients is generally high (11), whereas that of cryptogenic OP patients tends to be lower than 1 (13,14). These findings are also inconsistent with hot tub lung.

The 2007 ATS/IDSA guidelines recommend 2–4 months of intravenous amikacin plus cefoxitin or imipenem combined with oral macrolides, such as clarithromycin or azithromycin, but there was little concrete evidence supporting these guidelines, which noted that an effective antibiotic regimen that could cure M. abscessus was not known (7). Several recent studies regarding treatment outcome in M. abscessus complex lung disease have been reported, with positive results ranging from 25% to 88% (15-17). The results of these studies may not be generalizable to all patients, because these were retrospective studies utilizing various regimens with different treatment durations, and many patients included in these studies received treatment in combination with surgery. Furthermore, it has been reported that Mycobacterium massilience (M. massilience) is a separate species from M. abscessus complex and treatment including clarithromycin is more effective in patients with M. massilience than M. abscessus infection (15).

In conclusion, we reported a very rare case of ARF due to pulmonary M. abscessus infection accompanied by OP that was successfully treated with an anti-mycobacterial treatment and systemic corticosteroids. To the best of our knowledge, M. abscessus lung disease accompanying OP has not been described in the English language literature, with the exception of only one case diagnosed with bronchial washing and TBLB (6). Pulmonary M. abscessus infection can present different clinicopathological features according to the various immune responses of the host. Respiratory physicians should be aware that pulmonary M. abscessus infection can develop simultaneous OP with ARF and should make conscientious effort to identify organisms causing unusual lung infections.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this manuscript and any accompanying images.

References

- Cordier JF. Cryptogenic organising pneumonia. Eur Respir J 2006;28:422-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Al-Ghanem S, Al-Jahdali H, Bamefleh H, et al. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia: pathogenesis, clinical features, imaging and therapy review. Ann Thorac Med 2008;3:67-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tse GM, To KF, Chan PK, et al. Pulmonary pathological features in coronavirus associated severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). J Clin Pathol 2004;57:260-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hwang DM, Chamberlain DW, Poutanen SM, et al. Pulmonary pathology of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Toronto. Mod Pathol 2005;18:1-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yoon HS, Lee EJ, Lee JY, et al. Organizing pneumonia associated with M ycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Respirol Case Rep 2015;3:128-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nakahara Y, Oonishi Y, Takiguchi J, et al. Nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease accompanied by organizing pneumonia. Intern Med 2015;54:945-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;175:367-416. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hamada K, Nagai S, Hara Y, et al. Pulmonary infection of Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex with simultaneous organizing pneumonia. Intern Med 2006;45:15-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jones RM, Dawson A, Evans EN, et al. Co-existence of organising pneumonia in a patient with Mycobacterium avium intracellulare pulmonary infection. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis 2009;71:76-80. [PubMed]

- Starobin D, Guller V, Gurevich A, et al. Organizing pneumonia and non-necrotizing granulomata on transbronchial biopsy: coexistence or bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia secondary to Mycobacterium kansasii disease. Respir Care 2011;56:1959-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marras TK, Wallace RJ Jr, Koth LL, et al. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis reaction to Mycobacterium avium in household water. Chest 2005;127:664-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hanak V, Kalra S, Aksamit TR, et al. Hot tub lung: presenting features and clinical course of 21 patients. Respir Med 2006;100:610-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Izumi T, Kitaichi M, Nishimura K, et al. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia. Clinical features and differential diagnosis. Chest 1992;102:715-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Poletti V, Cazzato S, Minicuci N, et al. The diagnostic value of bronchoalveolar lavage and transbronchial lung biopsy in cryptogenic organizing pneumonia. Eur Respir J 1996;9:2513-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Koh WJ, Jeon K, Lee NY, et al. Clinical significance of differentiation of Mycobacterium massiliense from Mycobacterium abscessus. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;183:405-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lyu J, Jang HJ, Song JW, et al. Outcomes in patients with Mycobacterium abscessus pulmonary disease treated with long-term injectable drugs. Respir Med 2011;105:781-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jarand J, Levin A, Zhang L, et al. Clinical and microbiologic outcomes in patients receiving treatment for Mycobacterium abscessus pulmonary disease. Clin Infect Dis 2011;52:565-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]