Glomus tumors of the trachea: 2 case reports and a review of the literature

Introduction

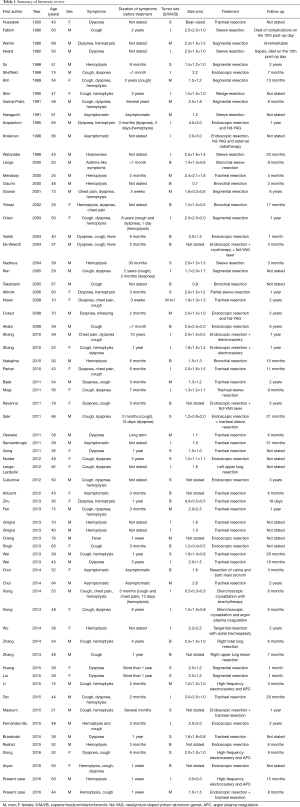

Glomus tumors (GTs) are rare mesenchymal tumors composed of modified smooth muscle cells and normal glomus body cells that constitute less than 2% of all soft tissue tumors. The World Health Organization [2002] defined GTs as benign tumors comprising perivascular cells (1). This type of neoplasm was first reported in 1924 by Masson (2). Here, we describe two cases of GT that occurred in the trachea. In addition, we describe the findings of a comprehensive literature search of the PubMed database using “glomus tumor of trachea” and “bronchial glomus tumor” as key words. Sixty-eight cases of GT of the trachea have been reported publicly. The vast majority of the relevant articles are case reports, and their characteristics are presented in Table 1. We also review pertinent literature and discuss the clinical manifestations, pathological types, immunohistochemical expression patterns, differential diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of GTs.

Full table

Case presentation

Case 1

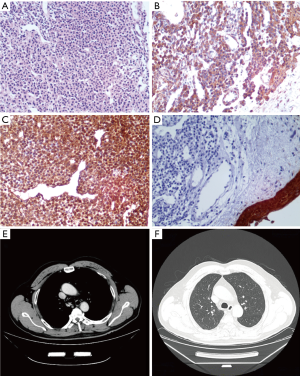

A 63-year-old man with a 49-year history of cigarette smoking (49 packs/year) was admitted for a 1-week history of hemoptysis. The patient also complained of occasional cough and chest pain. He exhibited hypertension, but his physical examination demonstrated no abnormalities. A chest computed tomography (CT) series revealed the presence of a 0.5×0.3 cm2 solid lesion in the lower portion of the trachea, near its posterior wall (Figure 1A,B). Bronchoscopy revealed the presence of a cauliflower-like neoplasm with a rich blood supply arising from the posterior membrane of the lower trachea (Figure 1C). Bronchoscopic biopsy revealed the presence of a small round cell tumor, likely a GT, although it was necessary to rule out a diagnosis of a neuroendocrine tumor. Immunohistochemical staining demonstrated positive reactivity for vimentin (VIM), smooth muscle actin (SMA), Calponin and Bcl-2 and negative reactivity for cytokeratin (CK), NapsinA, Syn, CgA and CD34. Thus, a diagnosis of GT was made (Figure 2A-D). The patient was advised to undergo surgical treatment but refused because of the risks associated with surgery. He bled profusely during the fiberoptic bronchoscopy; therefore, we performed bronchial artery embolization (BAE) before performing bronchoscopic resection. The patient underwent high-frequency electrocauterization and flexible bronchoscopic argon-plasma coagulation (APC) for tumor removal. CT demonstrated no obvious abnormalities when the patient was reexamined 3 months after the procedure (Figure 2E,F), and the patient exhibited no symptoms or signs of recurrence when last examined at 15 months post-treatment. At present, the patient 1 described herein remains in good condition.

Case 2

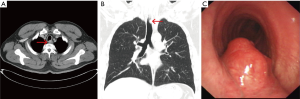

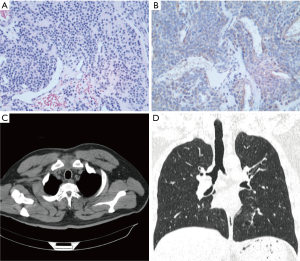

A 44-year-old never smoking man was admitted for a 1-week history of cough and hemoptysis. His physical examination demonstrated no abnormalities. Chest CT revealed the presence of a 1.0×1.5 cm2 nodular lesion on the posterior wall of the upper portion of the trachea (Figure 3A,B). Bronchoscopy demonstrated a neoplasm rich in blood vessels arising from the posterior membrane of the upper trachea (Figure 3C). The patient subsequently underwent high-frequency electrocautery for tumor removal. Microscopically, the tumor consisted mainly of round or ovoid glomus cells surrounding thin-walled blood vessels. VIM, Syn and Bcl-2 immunohistochemical staining was positive, and SMA immunohistochemical staining was suspectedly positive. In contrast, desmin, CK, CD56, CD34 and EMA immunohistochemical staining was negative. The histological characteristics of the tissues were consistent with those of a neuroendocrine tumor, particularly a carcinoid tumor. The patient therefore underwent tracheal neoplasm resection and tracheoplasty. His surgery revealed that the diameter of his neoplasm was approximately 1 cm and that the lesion involved a portion of the middle tracheal wall approximately 20 cm from the incisors. Immunohistochemical staining demonstrated positive reactivity for VIM, SMA, Syn, Collagen IV and Bcl-2. The histological characteristics and immunohistochemical staining pattern of the tumor were consistent with the diagnosis of GT (Figure 4A,B). The tumor had infiltrated the smooth muscle, and this infiltration was accompanied by bone metaplasia and neuroendocrine marker expression. CT (Figure 4C,D) was repeated 3 months later and produced normal results, and the patient exhibited no evidence of recurrence 8 months after the procedure. However, patient 2 exhibited infiltrative tumor growth, as well as smooth muscle involvement, bone metaplasia and neuroendocrine expression. Therefore, patient 2 requires long-term follow-up.

Discussion

Clinical epidemiology

GTs normally present as spheres comprising arterial and venous anastomoses that can be found over nearly the entire body (3). Glomus bodies are responsible for temperature control on the skin surface (4). Arteriovenous anastomoses are more common in the extremities than in other locations. In particular, GTs often develop in the nail beds of the extremities. Such tumors account for approximately 70% of all GTs, and lesions involving the torso and head and neck account for 20% of all GTs. GTs have also been reported to occur at unusual locations, such as the nose, sinuses, thoracic region, kidneys, stomach, mediastinum, heart, intestines, muscles, vagina, tendons, ligaments and lungs. Tracheal glomus tumors (TGTs) are fairly rare (5-12).

Macroscopic presentation

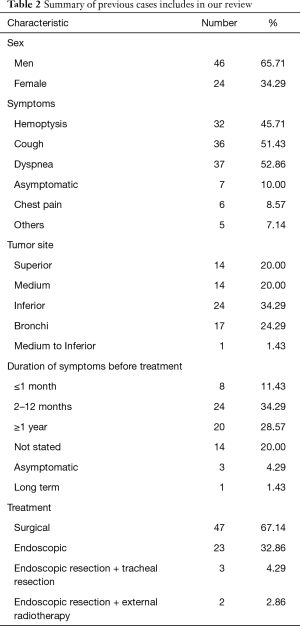

To our knowledge, 70 cases of GT, including those described in the above case reports, have been reported in literature to date. A summary of the clinical characteristics of and treatments provided for these previously reported GTGs is presented in Tables 1,2. This disease commonly occurs in middle-aged people and is more common among men than among women; specifically, the male: female ratio is 1.92:1. The average age of presentation is 48.8 years (range: 10–83 years). Some patients are asymptomatic (10%); therefore, their diagnoses require a medical examination. The most commonly presenting symptoms among symptomatic GT patients are dyspnea (52.86%), cough (51.43%) and hemoptysis (45.71%). Less frequently, patients can present with chest pain (8.57%). Hoarseness and fever are rare, as only approximately 7.14% of patients present with those symptoms. Most patients (64.29%) have the illness for longer than 1 month before presentation, and the longest reported disease duration before presentation is 10 years, suggesting that this type of tumor grows slowly. Physical examination findings often include low blood pressure, heart rate and respiratory rate, inspiratory dyspnea and wheezing, which is most audible above the clavicle or at the sternal midline during inspiration. Glands and blood vessels are more abundant in the lower bronchial mucosa than in the upper and middle bronchial mucosa (13). Kim et al. (14) reported that glomus-like structures can also be found in the tracheal membranous wall. Specifically, TGTs often occur in the posterior membranous wall of the lower trachea. The statistics regarding the locations of TGTs (upper: 20%, middle: 20%, lower: 34.29%, and bronchi: 24.29%) indicate that the lower 1/3 of the trachea is a common location. To date, only one GT, which was described in a case report by Haver et al. (15), has been demonstrated to involve the middle-lower portion of the trachea. In this study, patient 1 presented with a 0.5×0.3 cm2 tumor, the smallest GT reported to date. In contrast, Vailati has described tumors as large as 5×1.5 cm2. GTs are usually small, exhibiting a diameter of 1.0–2.5 cm, and generally display a clear border, a smooth surface, and numerous capillaries. Most of these tumors are benign and are thus unlikely to exhibit distant metastasis or deep infiltration. Zhang et al. (16) described a GT originating from the right main bronchus that obstructed the bronchial cavity and invaded the upper and middle portions of the bronchus, and Huang et al. (17) described a GT in the upper bronchus with invasive growth involving all layers of the bronchial wall and the outer membrane of the esophagus. Fernandez-Bussy et al. (18) described GTs involving the trachea and the left forearm. The possibility of other distant metastases could not be completely ruled out in these cases.

Full table

Microscopic features

Regarding morphology, GTs can present as single tumors or multiple tumors and can also exhibit distant metastases. Multiple GTs are rare and account for approximately 10–25% of GT cases (13). Typical GTs are classified as solid GTs, glomangiomas and glomangiomyomas, depending on their dominant component (19). The classification system proposed by Folpe et al. (20) in 2001 organized atypical GTs into the following categories: malignant GTs (MGTs), GTs of uncertain malignant potential (UMPGTs), symplastic GTs (SGTs) and glomangiomatosis (GGS). Despite being benign lesions, GTs may behave as aggressive and malignant tumors. The literature regarding MGTs and UMPGTs indicates that approximately 10 cases have been reported thus far and that the incidence of these tumors has gradually increased in recent years. The diagnosis of MGT is reserved for tumors larger than 2 cm in a subfascial or visceral location showing atypical mitotic figures or marked nuclear atypia and exhibiting any level of mitotic activity. The diagnosis of UMPGT is reserved for superficial tumors exhibiting high mitotic activity, deep tumors or large tumors.

Histological and immunohistochemical features

Carcinoid tumors and hemangiopericytomas arise from the submucosa of the trachea, and consist of sheets and nests of cells surrounding numerous vascular spaces (21). Therefore, they are easily mistaken for GTs. Our second patient underwent neoplasm resection because he was diagnosed with a carcinoid tumor via bronchoscopic biopsy. This diagnosis was confirmed via postoperative pathological examination. We identified three patients who exhibited similar presentations. As TGTs are easily missed and often misdiagnosed, we diagnose these tumors on the basis of their histopathological characteristics and immunohistochemical staining patterns (Table 3). GT cells are round or oval in shape and line up tightly. They exhibit strong positive staining for SMA, VIM and type IV collagen but do not stain positive for neuroendocrine and epithelial markers, including chromogranin, CK, desmin and S-100 protein. Carcinoid tumors have less vascular mass, and their cells are arranged as nests. These tumors stain positive for neuroendocrine markers, such as NSE, CgA, chromogranin and synaptophysin, but stain negative for SMA and VIM. Hemangiopericytomas usually consist of new blood vessels and stroma and display staghorn-like vascular features. These tumors stain positive for CD34, Bcl-2 and VIM but stain negative for desmin and SMA.

Full table

Treatment

Surgery is considered the first-choice treatment for GT. The currently available data indicate that 67.14% of the 70 reported patients were ultimately treated via surgical resection and that 32.86% of patients underwent endoscopic removal of their tumors. Currently, segmental tracheal resection with an end-to-end anastomosis is the preferred method of treating GTs surgically. However, some patients have been treated via tracheal sleeve resection or tracheal wedge resection. Wu et al. (22) proposed performing a longitudinal resection with spiral tracheoplasty. This method can significantly mitigate tracheal tissue injury and is therefore applicable for patients with larger lesions requiring more extensive tracheal resection. Endobronchial therapy can be administered to patients who are unfit for surgical excision or who refuse surgery. Common endobronchial therapy techniques include laser resection, high-frequency electrocoagulation and APC. Because TGTs have a rich blood supply, bronchoscopic biopsy with forceps should be avoided. In this study, patient 1 experienced severe bleeding during his fiberoptic bronchoscopy. Therefore, bronchoscopic resection was performed after BAE, during which the patient experienced only a small amount of intraoperative bleeding. However, the feasibility and necessity of this method remain unknown. Masoum et al. (23) reported the case of a 21-year-old male patient who underwent bronchoscopic GT resection who experienced postoperative recurrence after 1 year. The patient underwent another resection and exhibited no signs of recurrence after 1 year of follow-up. Therefore, TGT patients should be treated with surgery instead of bronchoscopic therapy.

Prognosis

To date, the reports in the literature indicate that 2 of the 70 patients with GT died of postoperative complications, whereas the remaining patients have been followed for periods ranging from 1–5 years and have exhibited good recovery in most cases. Distant metastasis of MGT is the major cause of death. The rate of metastasis is 31.2–38.0% (20), and tumors often recur between 3 and 4 years after surgery (24). However, Choi et al. (25) reported a case of TGT in which a postoperative bronchoscopy performed 2 months after surgical resection demonstrated a white neoplasm at the anastomosis site. Pathological examination revealed the presence of a granuloma, although a malignant GT could not be completely ruled out. Therefore, a bronchoscopic en bloc resection was performed. There have been rare reports regarding the use of adjuvant chemotherapy after TGT surgery, namely, two reports by Koskinen et al. (26) and Xiong et al. (27), respectively, and the effectiveness of this therapy is currently unclear.

Acknowledgements

Funding: This work was supported by the Jiangsu Province Natural Science Foundation, China (SBK2017042749), Medical Scientific Research Foundation of Jiangsu Province, China (Grant No. 324), and Jiangsu Province’s Young Medical Talents Program, China (QNRC2016600).

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for publication of this manuscript and any accompanying images.

References

- Jo VY, Fletcher CD. WHO classification of soft tissue tumours: an update based on the 2013 (4th) edition. Pathology 2014;46:95-104. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shen J, Shrestha S, Yen YH, et al. Pericyte Antigens in Perivascular Soft Tissue Tumors. Int J Surg Pathol 2015;23:638-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shrestha S, Shen J, Giacomelli P, et al. Ang-2 but not Ang-1 expression in perivascular soft tissue tumors. J Orthop 2016;14:147-153. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kleontas A, Barbetakis N, Asteriou C, et al. Primary glomangiosarcoma of the lung: A case report. J Cardiothorac Surg 2010;5:76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Geramizadeh B, Khorshidi A, Hodjati H. Chronic Long Standing Shoulder Pain, Caused by Glomus Tumor. Rare Tumors 2015;7:5666. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Troller R, Soll C, Breitenstein S. Glomus tumour of the stomach. BMJ Case Rep 2016.2016. [PubMed]

- Lamba G, Rafiyath SM, Kaur H, et al. Malignant glomus tumor of kidney: the first reported case and review of literature. Hum Pathol 2011;42:1200-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Elkrinawi R, Usta E, Baumbach H, et al. Late recurrence of a cardiac glomus tumor. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012;60:305-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez JM, Idoate MA, Pardo-Mindán FJ. The role of mast cells in glomus tumours: report of a case of an intramuscular glomus tumour with a prominent mastocytic component. Histopathology 2003;42:307-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yilmaz A, Bayramgurler B, Aksoy F, et al. Pulmonary glomus tumour: a case initially diagnosed as carcinoid tumour. Respirology 2002;7:369-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Miettinen M, Paal E, Lasota J, et al. Gastrointestinal glomus tumors: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 32 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2002;26:301-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Okereke IC, Sheski FD, Cummings OW. Glomus tumor of the trachea. J Thorac Oncol 2011;6:1290-1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schiefer TK, Parker WL, Anakwenze OA, et al. Extradigital glomus tumors: a 20-year experience. Mayo Clin Proc 2006;81:1337-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim YI, Kim JH, Suh JS, et al. Glomus tumor of the trachea. Report of a case with ultrastructural observation. Cancer 1989;64:881-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Haver KE, Hartnick CJ, Ryan DP, et al. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 10-2008. A 10-year-old girl with dyspnea on exertion. N Engl J Med 2008;358:1382-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang X, Zhu Y, Wang X, et al. Bronchial glomus tumor: report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi 2014;37:758-63. [PubMed]

- Huang C, Liu QF, Chen XM, et al. A malignant glomus tumor in the upper trachea. Ann Thorac Surg 2015;99:1812-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Bussy S, Labarca G, Rodriguez M, et al. Concomitant tracheal and subcutaneous glomus tumor: Case report and review of the literature. Respir Med Case Rep 2015;16:81-5. [PubMed]

- Sakr L, Palaniappan R, Payan MJ, et al. Tracheal glomus tumor: a multidisciplinary approach to management. Respir Care 2011;56:342-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Folpe AL, Fanburg-Smith JC, Miettinen M, et al. Atypical and malignant glomus tumors: analysis of 52 cases, with a proposal for the reclassification of glomus tumors. Am J Surg Pathol 2001;25:1-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gowan RT, Shamji FM, Perkins DG, et al. Glomus tumor of the trachea. Ann Thorac Surg 2001;72:598-600. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu HH, Jao YT, Wu MH. Glomus tumor of the trachea managed by spiral tracheoplasty. Am J Case Rep 2014;15:459-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Masoum SH, Jafarian AH, Attar AR, et al. Glomus tumor of the trachea. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 2015;23:325-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang Y, Li H, Zhang WQ. Malignant glomus tumor of the esophagus with mediastinal lymph node metastases. Ann Thorac Surg 2013;96:1464-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Choi IH, Song DH, Kim J, et al. Two cases of glomus tumor arising in large airway: well organized radiologic, macroscopic and microscopic findings. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul) 2014;76:34-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Koskinen SK, Niemi PT, Ekfors TO, et al. Glomus tumor of the trachea. Eur Radiol 1998;8:364-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xiong W, Cai C, Zhou Y, et al. Tracheal glomus tumor: two cases with bronchoscopic intervention. Chin Med J (Engl) 2014;127:189-90. [PubMed]