Is uniportal thoracoscopic surgery a feasible approach for advanced stages of non-small cell lung cancer?

Introduction

Despite the multiple advantages of video-assisted thoracoscopic (VATS) compared with thoracotomy (1) as decreased postoperative pain, decreased hospitalization, diminished inflammatory response or faster access to chemotherapy, the thoracoscopic approach for advanced stages of lung cancer is still infrequent. The concern about an intraoperative thoracoscopic major bleeding or the technical complication of performing a radical oncologic resection by VATS in advanced cases are the main reasons for the low adoption.

There are few studies reporting perioperative results and survival of patients with advanced disease operated by thoracoscopic approach (2,3). These cases are operated by using conventional VATS. However the same procedure can be performed by using a single incision approach. Since we developed our uniportal technique for VATS lobectomies in 2010 (4) we have increased the application of this technique to more than 90% of cases in our routine surgical practice. The experience we acquired with the uniportal technique during the last years (5), as well as technological improvements in high definition cameras, development of new instruments, vascular clips and more angulated staplers have made this approach safer, incrementing the indications for single-port thoracoscopic resections. We believe it is important to minimize the surgical aggressiveness especially in advanced stage lung cancer patients where the immune system is weakened by the disease or by neoadjuvant treatments. The minimally invasive surgery represents the least aggressive form to operate lung cancer and the single-port or uniportal technique is the final evolution in these minimally invasive surgical techniques.

The objective of this study is to assess the feasibility of uniportal VATS approach in the treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and to compare the perioperative outcomes and overall survival with early-stage tumors.

Methods

A retrospective descriptive prevalence study was performed on patients undergoing single-port approach for major pulmonary resections at Coruña University Hospital and Minimally Invasive Thoracic Surgery Unit (UCTMI) between June 2010 and December 2012. This study was approved by the review board at Coruña University Hospital and UCTMI. All patients were informed and had a written consent before surgery. A total of 163 surgical interventions (major pulmonary resections) were performed using this technique during the study period. Most were conducted by surgeons experienced with the uniportal approach for minor and major resections.

Only NSCLC were included in the study. Advanced clinical stage NSCLC were considered as tumors bigger than 5 cm, T3 or T4 and/or tumors that received neoadjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Most of the patients underwent routine preoperative pulmonary function testing, bronchoscopy, computed tomography, and fused positron emisión tomography-computed tomography.

Patients were divided into two groups: (A) early stage (T1 and T2) and (B) advanced clinical stages. A descriptive and retrospective study was performed, comparing perioperative outcomes and survival obtained in both groups.

Thanks to our previous VATS experience with conventional and double-port VATS (6), the indications and contraindications have changed overtime. The only absolute contraindication considered was surgeon discomfort and huge tumors impossible to remove without rib spreading.

Variables studied in each patient were age, sex, smoking habits, COPD, pulmonary function (FEV1 and FVC), presence of associated comorbidities, how the lesion is presented, tumor type and location, type and duration of surgical intervention, surgery-associated adhesions, stage, histology, tumor size, lymph nodes affected (number of lymph nodes retrieved and number of nodal stations explored), duration of chest tube, length of hospital stay, postoperative complications, 60-day mortality and survival.

Statistical analysis

A descriptive analysis of the variables studied was carried out. The quantitative variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, median and range. Qualitative variables are expressed by means of frequencies and the corresponding percentages. SPSS 17 for Windows for statistical analysis.

To compare the postoperative course according to perioperative characteristics, the Mann Whitney test was used for quantitative variables and Chi square test or Fisher exact test was used for qualitative variables.

A survival analysis was performed with Kaplan-Meier curves and the log-rank test was used to compare survival between patients with early and advanced stages.

Surgical technique

All patients in both groups were operated by using a single-incision VATS approach with no rib spreading and no wound protector (7). No epidural catheter was used. The 4-5 cm incision was placed in the fifth intercostal space. Anatomic major pulmonary resections were performed in all patients. Following anatomical resection, a complete mediastinal lymphadenectomy was performed in the patients with a diagnosis of malignancy. Instruments used were long and curved with proximal and distal articulation to allow the insertion of 3 or 4 instruments simultaneously and the camera used was 10 mm HD scope 30 degree. Intercostal infiltration was performed at the end of the surgery under thoracoscopic view and only one chest tube was placed in all patients.

We always start all lung operations with uniportal VATS to assess the extent of the disease and to rule out any pleuro-pulmonary metastasis. Conversions were defined as operations that began with a thoracoscopic dissection-division of hilar structures and were concluded as ribspreading thoracotomies. The cases that required conversion to open surgery were performed by extending the existing incision and continuing surgery through an anterior minithoracotomy with rib spreading and support of optics (like hybrid VATS).

Results

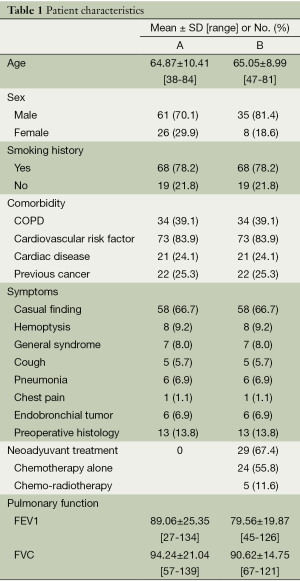

Since the start of the Uniportal VATS program in June 2010 until December 2012, we have performed 163 major lung resections using this technique (That is now, December 2013, a total of 323 major resections). Only NSCLC cases were included in this study so a total of 130 cases were studied: 87 (group A) vs. 43 patients (group B). The demographic characteristics of the patients in both groups are described in Table 1. There were no significant differences in terms of patient age, sex, smoking status, past medical history or associated comorbidity between the two groups. The lesions were most often casual findings (66.7% in group A and 37.2% in B). From the patients in group B, 67.4% of them received chemo or chemo-radiotherapy induction treatment before surgery.

Full table

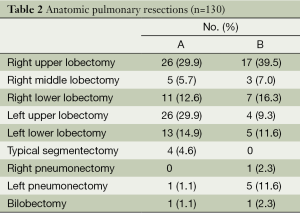

The types of resection performed and their frequency are shown in Table 2. Upper lobectomies (A, 52 vs. B, 21 patients) and anatomic segmentectomies (A, 4 vs. B, 0) were more frequent in group A while pneumonectomy was more frequent in B (A, 1 vs. B, 6 patients).

Full table

In group A, 68.3% of the patients and 40% of those in group B showed no adherences following lung collapse. In contrast, significant adherences complicating surgery were recorded in 15.4% of the cases in group A and 28.9% in group B.

The advanced group included very complex cases like bronchial sleeve resections, lobectomies with vascular reconstruction, chest wall resection, lobectomies after high doses of chemo-radiotherapy, redo-VATS, completion pneumonectomy or sulcus tumor after induction treatment.

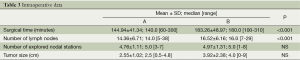

The intraoperative results are described in Table 3. Conversion rate was higher in group B (1.1% vs. 6.5%, P=0.119). Also in group B, surgical time was longer (144.9±41.3 vs. 183.2±48.9, P<0.001) and median number of lymph nodes (14 vs. 16, P=0.004) was statistically higher in advanced cases.

Full table

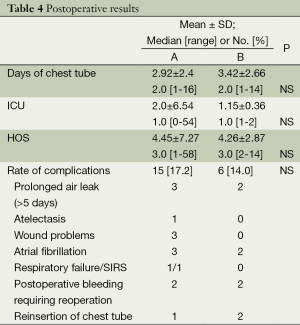

The postoperative results are described in Table 4. There were no significant differences in terms of days of stay in the intensive care unit, days of chest tube, HOS and rate of complications. One patient died on the 58th postoperative day due to a respiratory failure (group A).

Full table

In both groups the majority of the patients (A, 82.8% and B, 86%) suffered no postoperative complications. From the patients in group A, 65.5% of them were discharged in the first 72 hours versus 51.2% of patients in group B. All patients (100%) were discharged without any nursing assistance at home.

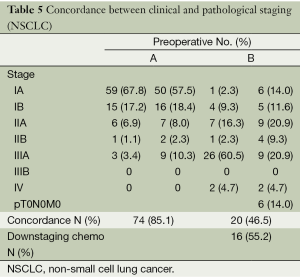

The most common histological type in group A (48, 55.1%) was adenocarcinoma while in group B (24, 55.8%) it was squamous cell carcinoma. The concordance between clinical and pathological stages is described in Table 5. A total of 85.1% of patients (A) and 46.5% (B) presented concordance between preoperative and postoperative staging. From the patients receiving chemotherapy 55.2% (16 patients) were pathologically downstaged (six of them were down-staged to pT0N0M0, total tumoral regression).

Full table

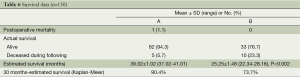

The survival rates are described in Table 6. The 30-month survival was 90.4% for early stages (group A) and 73.7% for advanced cases (group B). The 30-month overall survival of the 130 pacients was 85% (Kaplan-Meier).

Full table

Discussion

Since the first lobectomies using VATS were reported 20 years ago (8), the thoracoscopic approach has experienced an exponential increase for lung cancer treatment, especially for early stages. The majority of publications on VATS lobectomy focus on patients with early stages of NSCLC, showing less postoperative pain, lower stress responses and improved outcomes, when compared with thoracotomy (9). However the role of VATS for treatment of advanced stages of lung cancer is not clear and has been questioned.

Thanks to the advances in the field of thoracoscopic surgery the indications and contraindications for lung cancer treatment have been changed overtime. Initially only early stages were considered for VATS approach and advanced NSCLC tumors were considered a contraindication for thoracoscopic surgery (10). Several concerns regarding the radicality of oncologic resection, technical challenges, and safety has reduced the incorporation of VATS for more advanced stages of lung cancer. In cases of extended resections such as vascular or bronchial sleeve, chest wall resection or tumors after high doses of induction chemo-radiotherapy; the VATS approach is even less frequent. However, thoracoscopic major lung resection for advanced stage lung cancer is now gaining wide acceptance in experienced VATS departments (11). Skilled VATS surgeons can perform 90% or more of their lobectomies thoracoscopically, reserving thoracotomy only for huge tumors or complex broncho-vascular reconstructions.

Despite the increasing implementation of the techinque by experienced surgeons to deal with advanced tumors, the number of publications showing results is still insignificant. Hennon and colleagues, showed similar outcomes of advanced cases performed by VATS when compared with open surgery (2). In this study the perioperative complications were equal in patients undergoing thoracoscopic resection when compared to those having a thoracotomy. No difference was observed for disease-free and overall survival.

In another multi-institutional experience, more than 400 patients with stage III or IV disease were treated with a VATS approach over a period of 8 years. The preliminary analysis indicate no significant difference in overall survival between VATS and open thoracotomy groups, with a conversion rate of approximately 5% in the cohort of patients with advanced stage NSCLC (12).

The incidence of surgical complications after neoadjuvant therapy has been reported in the literature to be high (13). VATS lobectomy has been usually avoided in patients undergoing preoperative chemotherapy or radiotherapy due to concerns regarding the propensity of induction therapy to increase the difficulty of hilar and mediastinal dissection, especially around vessels. In our series of patients the induction treatment increased the complexity of hilar and lymph node dissection but these were performed successfully, most likely due to our previous thoracoscopic experience (5,6). There are publications reporting that pulmonary resection may be performed safely after induction chemo or high doses of radiotherapy (14,15). However, recent publications showed prior chemotherapy as one of the significant predictors of morbidity in a multivariable analysis (16). The rate of complications in our study in patients receiving induction treatment had not increased, being similar to perioperative results in early stage tumors.

Recently, Huang J and colleagues published a study of 43 locally advanced NSCLC patients (including nine sleeves and four pneumonectomies) undergoing VATS following neoadjuvant therapy with good posotperative results (3). Lee and colleagues report that thoracoscopic pulmonary resection for NSCLC showed better compliance with adjuvant chemotherapy, allowing to apply the thoracoscopic procedure not only to patients with early stage NSCLC but also to patients who need adjuvant chemotherapy (17).

Uniportal VATS has become an increasingly popular and effective approach in our unit to manage early and advanced stages of NSCLC, because of the reduced access trauma, advantages in view and more anatomic instrumentation and good perioperative results. The success in performing uniportal complex VATS lobectomies is a result of skills and experience accumulated over time from performing uniportal VATS surgery (5). With gained experience with the uniportal VATS technique the most complex cases can be performed in the same manner as with double or triple port approach. We have performed advanced NSCLC cases via single-port VATS including lobectomies with chest wall resection (18), redo-VATS and completion pneumonectomies, cases after high doses of chemo-radiotherapy, vascular reconstruction (19), bronchial sleeve lobectomies (20) and complex pneumonectomies (21).

Mean operation time for advanced uniportal VATS resections was higher than for early stage tumors (188 vs. 141 m), as expected. However our surgical time is less than other authors by using more number of thoracoscopic incisions (11). We found several advantages of the single incision technique especially for advanced cases. The geometrical explanation of the approach could explain our results (22). The advantage of using the camera in coordination with the instruments is that the vision is directed to the target tissue, bringing the instruments to address the target lesion from a straight perspective, thus we can obtain similar angle of view as in open surgery. Bimanual instrumentation also facilitates the surgery for complex cases. Conventional three port triangulation makes a forward motion of VATS camera to the vanishing point. This triangulation creates a new optical plane with genesis of dihedral or torsional angle that is not favorable with standard two-dimension monitors. Instruments inserted parallel to the videothoracoscope also mimic inside the chest maneuvers performed during open surgery. There is a physical and mathematical demonstration about better geometry obtained for instrumentation and view in the uniportal VATS over conventional approach (22). This fact in combination with the expierence obtained so far as well as recent improvements in surgical instruments, new energy devices and modern high definition cameras enable us to be very confident with the instrumentation and the manipulation of tissue even in very complex and advanced procedures.

The rate of pneumonectomies was logically higher in patients with advanced stages.

Pneumonectomy is only considered in cases where it is not possible to perform a sleeve resection. In our unit it is mandatory to do a careful assessment of the location of the tumor in order to proceed with a uniportal VATS pneumonectomy. Sleeve resections are also performed via single-incision VATS with no need to convert to thoracotomy allowing patients a better postoperative recovery (23). This is especially important in patients receiving induction chemo-radiotherapy as performing a pneumonectomy would increase the rate of postoperative complications. The uniportal thoracoscopic resection of the whole lung is technically easier to perform than a lobectomy because the fissure doesn’t need to be managed. However extra care must to be taken during dissection and division of the main artery and transection of the main bronchus (21). There are several studies reporting that pneumonectomies performed thoracoscopically or via thoracotomy resulted in equivalent survival rates (24). Further studies and follow-up is needed to verify the benefits of VATS pneumonectomy for lung cancer.

From the literature, conversion rates from VATS lobectomy to open surgery have been reported to be from 2% to 23%, with these higher rates coming from patients with more advanced tumors (2). Most frequently the conversion to thoracotomy was considered necessary because of bleeding during dissection or oncological reasons, such as centrally located tumors requiring sleeve resection, or unexpected tumors that infiltrate the mediastinum or chest wall. In our series, the rate of conversion for advanced cases is low (only 6.5%) compared with other series (2,3). Furthermore, no patient was converted to conventional thoracotomy in our study (enlarged incision to antherior thoracotomy and Hybrid VATS).

Also in our study, the incidence of postoperative complications in early stages and advanced stages were similar. The uniportal technique was developed in 2010 by one of the surgeons of the department and sequentially taught to a total of four consultant surgeons and two trainees. Most of the advanced cases were performed by the surgeon who developed the technique, and with more thoracoscopic experience. This surgeon’s experience in managing complex and highly difficult procedures under uniportal VATS and the advantages of the minimally invasive approach (small incision, no rib retractor and only one intercostal space opened) is also important to reduce the prevalence of postoperative complications, especially in the advanced group.

We believe that minimize the surgical aggression is particularly important given the large number of frail patients with advanced stage disease who require multimodality therapy, sometimes being difficult to tolerate in older patients or patients with severe comorbidity. Several articles in the literature suggest that the immune response is better preserved after VATS surgery than thoracotomy (1). Given that immune function is an important factor in controlling tumor growth and recurrence, we have hypothesized that the reduced inflammatory response associated with thoracoscopy, especially with uniportal VATS (which represents the minimal invasive approach) may be associated with improved long-term survival. Further studies to analyze inflamatory response and long term survival on uniportal VATS are ongoing.

This study is limited by its retrospective design and absence of comparative subjects with open approach. Most of the data except on present survival were collected from chart review, with the limitations accompanying a retrospective study. Also, the follow-up duration was relatively short, and the free-disease period was not studied making it difficult to conclude whether survival rates were favorable for patients undergoing uniportal VATS lobectomy.

Another limitation of the study is the absence of an analysis of the results based on the cases performed by surgeons with a greater experience in the technique (those who have performed most operations), compared to those surgeons who started the technique later.

There are few reports regarding perioperative results and survival of advanced cases of NSCLC operated by thoracoscopic approach. According to the VATS Consensus Statement (agreement among 50 international experts to establish a standardized practice of VATS lobectomy after 20 years of clinical experience), eligibility for VATS lobectomy should include tumour size ≤7 cm and N0 or N1 status. Chest wall involvement was considered a contraindication for VATS lobectomy, while centrality of tumour was considered a relative contraindication when invading hilar structure (25). The Consensus Group acknowledged the limitations of VATS lobectomy based on their individual experiences with a recommendation to convert to open thoracotomy in cases of major bleeding, significant tumour chest wall involvement and the need for bronchial and/or vascular sleeve procedures. However, these recommendations are directed at the general thoracic surgical community, and indications for VATS lobectomy and conversion to thoracotomy should depend on each surgeons experience.

In conclusion, Uniportal VATS lobectomy for advanced cases of NSCLC is a safe and reliable procedure that provides perioperative outcomes similar to those obtained in early stage tumours operated through this same technique. Our 30-month survival rate is acceptable and similar to survival rates reported in other studies performed by conventional VATS. Further analyses of long term survival for advanced cases operated by uniportal VATS needs to be performed with a large number of patients to validate the oncologic outcomes of the technique.

Acknowledgements

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Nagahiro I, Andou A, Aoe M, et al. Pulmonary function, postoperative pain, and serum cytokine level after lobectomy: a comparison of VATS and conventional procedure. Ann Thorac Surg 2001;72:362-5. [PubMed]

- Hennon M, Sahai RK, Yendamuri S, et al. Safety of thoracoscopic lobectomy in locally advanced lung cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2011;18:3732-6. [PubMed]

- Huang J, Xu X, Chen H, et al. Feasibility of complete video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery following neoadjuvant therapy for locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Dis 2013;5:S267-73. [PubMed]

- Gonzalez D, Paradela M, Garcia J, et al. Single-port video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2011;12:514-5. [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Rivas D, Paradela M, Fernandez R, et al. Uniportal video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy: two years of experience. Ann Thorac Surg 2013;95:426-32. [PubMed]

- Gonzalez D, de la Torre M, Paradela M, et al. Video-assisted thoracic surgery lobectomy: 3-year initial experience with 200 cases. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2011;40:e21-8. [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Rivas D, Fieira E, Delgado M, et al. Uniportal video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy. J Thorac Dis 2013;5:S234-5. [PubMed]

- Roviaro G, Rebuffat C, Varoli F, et al. Videoendoscopic pulmonary lobectomy for cancer. Surg Laparosc Endosc 1992;2:244-7. [PubMed]

- Hanna WC, de Valence M, Atenafu EG, et al. Is video-assisted lobectomy for non-small-cell lung cancer oncologically equivalent to open lobectomy? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2013;43:1121-5. [PubMed]

- Yang X, Wang S, Qu J. Video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) compares favorably with thoracotomy for the treatment of lung cancer: a five-year outcome comparison. World J Surg 2009;33:1857-61. [PubMed]

- Hennon MW, Demmy TL. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) for locally advanced lung cancer. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2012;1:37-42. [PubMed]

- Cao C, Zhu ZH, Yan TD, et al. Video-assisted thoracic surgery versus open thoracotomy for non-small-cell lung cancer: a propensity score analysis based on a multi-institutional registry. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2013;44:849-54. [PubMed]

- Venuta F, Anile M, Diso D, et al. Operative complications and early mortality after induction therapy for lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2007;31:714-7. [PubMed]

- Petersen RP, Pham D, Toloza EM, et al. Thoracoscopic lobectomy: a safe and effective strategy for patients receiving induction therapy for non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 2006;82:214-8; discussion 219. [PubMed]

- Maurizi G, D’Andrilli A, Anile M, et al. Sleeve lobectomy compared with pneumonectomy after induction therapy for non-small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2013;8:637-43. [PubMed]

- Villamizar NR, Darrabie M, Hanna J, et al. Impact of T status and N status on perioperative outcomes after thoracoscopic lobectomy for lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2013;145:514-20; discussion 520-1. [PubMed]

- Lee JG, Cho BC, Bae MK, et al. Thoracoscopic lobectomy is associated with superior compliance with adjuvant chemotherapy in lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 2011;91:344-8. [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Rivas D, Fernandez R, Fieira E, et al. Single-incision thoracoscopic right upper lobectomy with chest wall resection by posterior approach. Innovations (Phila) 2013;8:70-2. [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Rivas D, Delgado M, Fieira E, et al. Single-port video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy with pulmonary artery reconstruction. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2013;17:889-91. [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Rivas D, Fernandez R, Fieira E, et al. Uniportal video-assisted thoracoscopic bronchial sleeve lobectomy: first report. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2013;145:1676-7. [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Rivas D, de la Torre M, Fernandez R, et al. Video: Single-incision video-assisted thoracoscopic right pneumonectomy. Surg Endosc 2012;26:2078-9. [PubMed]

- Bertolaccini L, Rocco G, Viti A, et al. Geometrical characteristics of uniportal VATS. J Thorac Dis 2013;5:S214-6. [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Rivas D, Delgado M, Fieira E, et al. Left lower sleeve lobectomy by uniportal video-assisted thoracoscopic approach. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2014;18:237-9. [PubMed]

- Nwogu CE, Yendamuri S, Demmy TL. Does thoracoscopic pneumonectomy for lung cancer affect survival? Ann Thorac Surg 2010;89:S2102-6. [PubMed]

- Yan TD, Cao C, D’Amico TA, et al. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery lobectomy at 20 years: a consensus statement. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2014;45:633-9. [PubMed]