Chinese expert consensus on bronchial asthma control

Chinese and international guidelines for prevention and treatment of bronchial asthma (hereinafter referred to as asthma) indicate: the goal of asthma management is to achieve and maintain symptom control; treatment protocols need to be adjusted according to asthma control levels during asthma management; asthma management is a long-term process which incorporates three essential aspects—evaluation, treatment, and monitoring (1,2). These guidelines highlight that asthma control as the goal of treatment can be achieved by medication in the majority of patients, particularly with effective asthma management (1,2). The 2009 updates on the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) proposed a new conception of “overall asthma control”, which expanded the previous understanding of asthma control to emphasize the equal importance of achieving current asthma control and reducing future risk (3). However, a number of surveys in China and other countries have revealed that the rate of asthma control in the real world is far below as proposed by the guidelines (4-9). Poorly controlled asthma was shown to seriously affect the daily life, work and school of patients, and was associated with recurrent asthma exacerbations, unscheduled hospital visits and stay, and impaired lung functions, which eventually lead to increased treatment cost, lost productivity, as well as heavy social and economic burden (4-9). Therefore, with the updated understanding, efforts to improve the current pattern of asthma management and to reinforce the treatment strategies will have a long way to go for better outcomes of overall asthma control. In this regard, the Asthma Workgroup of Chinese Thoracic Society convened a panel meeting of experts in the related fields, which formed the following consensus. In order to guide clinical practicing, the present consensus was developed with reference to related guidelines and consensus documents published elsewhere, in particular, the important papers on asthma control that appeared in the recent years.

Definition of overall asthma control

Overall asthma control is proposed to include two aspects: (I) achieving current control, as characterized by no or few symptoms (≤2 times in a week), no or little need (≤2 times in a week) for reliever medications (such as inhaled short-acting β2-agonists), normal or nearly normal lung functions, and no limitations in daily activities; and (II) reduced future risks, as reflected by absence of unstable or worsening asthma symptoms, no asthma exacerbations, no persistent decline in lung function, and no adverse reactions related to long-term medications (10).

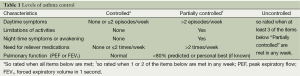

Overall asthma control is assessed by both the level of asthma control and future risks. The levels of asthma control, based on the patient’s symptoms and pulmonary function in the previous 4 weeks, are rated as “controlled”, “partially controlled”, or “uncontrolled” (Table 1). The future risks are evaluated in terms of asthma exacerbations, unstable disease, decline in lung function, and drug-related adverse reactions. Thereby, overall asthma control emphasizes on the relationship between future risks and current control (10).

Full table

Relationship between current asthma control and future risks

Evidence has accumulated in successfully preventing and reducing the future risks of several chronic diseases such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus (11-13). Asthma as a chronic disease should be managed with focus not only on achieving current control, but also on reducing the risks of unstable asthma and acute exacerbations in the future. In the GOAL (Gaining Optimal Asthma controL) study, patients who had achieved ‘total control’ and ‘well control’ of asthma in the study phase I continued to achieve their asthma control status in >90% and ~80%, respectively, of the duration in study phase II (14). A global multi-center clinical trial, which incorporated six major strategies of Single inhaler Maintenance And Reliever Therapy (SMART) and used Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ)-5 to evaluate asthma control, revealed that ~75% of the patients who had achieved control or partial control would maintain their asthma control levels years later, and that only 6% of the controlled asthma would be likely to revert back to uncontrolled status in the future (10).

The relationship between current control level and future risk is complicated because of multiple influencing factors. A lot more well-designed clinical trials are needed to elucidate on how to achieve an all-round reduction of future asthma risk, so as to provide further evidence for clinical practice. So far, factors known to be related to future risk of asthma include:

- Asthma exacerbations. As shown in a five-year follow-up study, decline in lung function was not apparent among asthma patients with no exacerbations who were either on inhaled glucocorticosteroids (hereinafter referred to as steroids) or on placebo; in contrast, among those who had experienced one or more exacerbations and were on placebo, there was a mean reduction by 7% in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), which was significantly greater as compared with asthma patients with no exacerbations. These findings suggested that occurrence of asthma exacerbations may accelerate lung function decline (15).

- Level of FEV1. A baseline FEV1 level can predict the frequency of future asthma exacerbations. Asthma patients with a lower baseline FEV1 level tend to have a higher frequency of asthma exacerbations in the future (16,17).

- Current asthma control. The clinical characteristics (daytime symptoms, limitation of activities, night-time symptoms, and “as-needed” use of reliever medications) adopted in GINA classification of asthma control level are the most valuable predictors of future risk. A good correlation between the scores of ACQ-5 or Asthma Control Test (ACT) and the GINA asthma control levels (controlled, partially controlled and uncontrolled) has been shown (18,19).

- Exposure to tobacco smoke. Currently smoking asthma patients are less likely to achieve a successful control. Tobacco smoke exposure is the most important modifiable factor that can be controlled to reduce future risk of asthma (2).

- Infections. Wheezing in children is typically associated with respiratory viral infections. Respiratory infection with syncytial virus may lead to refractory asthma. Infections with Aspergillus, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and Chlamydia infection may have a role in adult asthma (2). A recent large-scale retrospective study revealed that influenza virus remains the first leading trigger of asthma exacerbations (20).

- High-dose asthma medications. The need for high-dose inhaled steroids and/or LABAs in asthma patients are frequently predictive of poor control or future risk of asthma (2).

Assessment and monitoring

Proper assessment of asthma control and monitoring of the disease severity are clinically critical for prevention and treatment of asthma (2).

- Asthma symptom assessment. Clinically, certain questionnaires such as ACT (Appendix 1) and ACQ (Appendix 2) are commonly used to assess the control of asthma symptoms. Owing to satisfactory operability and clinical practicality, these questionnaires are suitable for use at primary healthcare institutions or in clinical trials.

- Pulmonary function tests. Pulmonary function tests can be helpful to determine the severity, reversibility and variation of airflow limitation, thereby providing evidence for the diagnosis of asthma and assessment of asthma control. Typically, a post-bronchodilator (e.g., 200-400 µg salbutamol) improvement in FEV1 ≥12% and ≥200 mL is diagnostic of asthma. However, most asthma patients will not exhibit such reversibility of airflow limitation at each assessment, particularly those who are on treatment. Peak flow meter are inexpensive, portable devices ideal to use in home settings for day-to-day monitoring of airflow limitation. A diurnal variation of ≥20% in peak expiratory flow (PEF) may help determine the diagnosis of asthma and worsening of the disease. Nevertheless, measurement of PEF by no means can be a perfect substitute for spirometry (e.g., FEV1), as it either overestimates or underestimates the severity of airflow limitation, especially when the condition is worsening.

- Airway inflammatory markers: Airway inflammation correlates closely with acute exacerbation and relapse of asthma. While the existing assessment systems of asthma control rely intensively on clinical indicators, it would be important to consider including airway inflammatory markers in these systems. The airway inflammation in asthmatics can be evaluated in many ways, such as measurement of airway hyperresponsiveness, induced sputum cytology, exhaled nitric oxide and breath condensate. However, owing to the methodological diversity, operational complexity and unsatisfactory reproducibility among these tests, technical improvements are further required before their widespread use in clinical practice. Recent literature has shown significant inconsistency between clinical indicators and airway inflammatory markers in patients with asthma, as reflected by earlier improvement in clinical indicators than in inflammatory markers among nearly one-third of the patients. Nevertheless, many studies so far have confirmed that detection of airway inflammatory markers can benefit asthma patients not only in assessing and monitoring current asthma control, but also in predicting future risk.

Achieving overall asthma control

The goal of asthma treatment and management is to achieve “overall asthma control”. Towards this goal, the approach of assessment, treatment and monitoring of asthma as proposed by GINA and Chinese Guideline for Prevention and Management of Bronchial Asthma should be followed (1,2).

- Proper assessment of asthma control: the levels of asthma control are rated as “controlled,” “partially controlled,” and “uncontrolled” based on the classification criteria for asthma control. Treatment steps should then be determined according to the specific asthma control level in the patients to achieve the goal of overall asthma control.

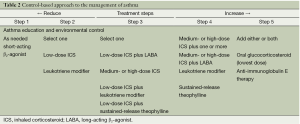

- Selection of treatment regimens: initial treatment regimen for asthma should be selected (Steps 1 through 5) based on assessment of disease severity (intermittent, mild persistent, moderate persistent and severe persistent asthma). During treatment, patients should be assessed repeatedly for level of asthma control with which the current treatment step is escalated or de-escalated accordingly. Except for those with intermittent asthma, all patients should be given long-term inhaled steroids; for severe cases, the inhaled steroids should be given in combination with other drugs (Table 2).

For patients whose symptoms are obviously uncontrolled, treatment should be started at Step 3; for those with uncontrolled asthma and poor lung function (post-bronchodilator FEV1 <80% predicted), at Step 4. Current guidelines recommend a combination of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) plus long-acting β2-agonist (LABA) as the first-line choice of initial treatment for patients with moderate to severe asthma (1,2). Budesonide/formoterol and fluticasone/salmeterol are presently the common ICS/LABA combinations used for initial maintenance therapy of moderate to severe asthma, given in recommended daily doses of 640/18 and 500/100 µg, respectively.

According to GINA, combination inhalers containing formoterol and budesonide can be used for both maintenance and rescue. Such a combination therapy has been demonstrated to contribute to enhanced protection from asthma exacerbations and provide improvements in asthma control at relatively low doses of steroids in adult and adolescent patients with asthma (Evidence A) (2). Furthermore, it was also found that the use of a combination inhaler containing a rapid and long-lasting β2 agonist (formoterol) plus an inhaled steroid (budesonide) as maintenance and rescue is effective in maintaining a high level of asthma control and reduces exacerbations requiring systemic glucocorticosteroids and and hospitalizations (Evidence A) (2). Given these, the guidelines propose a new treatment strategy, the Single inhaler Maintenance and Reliever Therapy (SMART), which involves the ICS/LABA combination for both maintenance and relief. A number of clinical studies have shown that, compared with other treatments, the use of a combination inhaler containing formoterol and budesonide as a SMART strategy may contribute to asthma control and a significant reduction in future risk of asthma among majority of patients, and ultimately help to achieve the overall asthma control (21-25). - Monitoring and maintaining asthma control. Down-stepping of the treatment may be considered only if asthma control has been achieved and maintained for at least 3 months. The severity of asthma should be closely monitored when stepping down the treatment; step up the treatment in response to worsening control (partially controlled or uncontrolled) until asthma control is achieved once again. De-escalation in the therapy is to establish the lowest step and dose of treatment to minimize drug-related adverse effects and medical cost (1,2). In patients who have achieved and maintained asthma control for 3 months on common ICS/LABA combination inhalers containing budesonide/formoterol or salmeterol/fluticasone and starting with an initial maintenance dose of 640/18 µg (budesonide/formoterol 160/4.5 µg, 2 puffs per time, twice daily) or 500/100 µg, respectively, the recommended daily dose for the immediately down-stepped maintenance therapy is 320/9 or 200/100 µg, respectively. Thereafter, for patients who continue to remain their asthma control status for at least 3 more months, consider single use of ICS alone in current dose. If the patient’s asthma remains controlled on ICS monotherapy for at least 3 more months, consider titrating ICS to the minimum dose required to maintain control. In individual patients, ICS may be stopped but their condition should be closely monitored so that the treatment is resumed when necessary.

Full table

Importance of patient management in improving asthma control

Asthma is a chronic disease that constitutes significant impact on patients, their family and the society. Good patient management may help achieve complete control of asthma. Owing to the disparities in culture and healthcare systems, the implementation of asthma management can vary from country to country, but typically involves five aspects as follows (1,2):

- Patient education. Medical education on asthma can help patients recognize early symptoms of asthma and minimize misunderstandings about the disease and treatment, so that they can seek timely medical attention. Patient education also helps establish a close partnership between healthcare workers and patients (and their family members) which will enable “guided self-management” of asthma. Obviously, asthma education is a long-term ongoing project that requires repetition, reinforcement, regular updates and perseverance.

- Monitoring asthma by integrating evaluation of symptoms and measurement of lung function. The shortened 5-questioned ACQ (ACQ-5) is commonly used in clinical research settings. Pulmonary function test can provide objective monitoring of asthma severity and patient response to therapy, thereby avoiding inadequate treatment due to underestimation of asthma symptoms by individual patients or healthcare providers. PEF monitoring is an easy-to-use procedure most commonly used for simple evaluation of the pulmonary function. Patients are advised to take home-monitoring of their PEF twice daily early during the treatment of asthma, and may reduce the frequency of PEF measurement when asthma control is achieved. Long-term PEF monitoring on a regular basis should be recommended particularly for patients who have ever been hospitalized for asthma or with poor perception of airflow limitation, in order to help them recognize early symptoms and avert the risk of fatal asthma attacks.

- Identifying and avoiding exposure to risk factors. A variety of environmental factors, including allergens, pollutants, food and drugs, may be involved in the onset of asthma or triggering an exacerbation. Patients and their family should be educated on how to identify these risk factors, and how these factors intersect with the development of asthma; they should be helped with effective measures to avoid exposure to risk factors.

- Planning for long-term management based on regular follow-up consultations. Prompt adjustment of asthma medication is needed according to the control level; the patient’s inhaler device techniques also need corrections and re-checking by physicians. All these rely on patient-physician interactions during routine follow-up consultations. At these visits, the patient’s questions are discussed, and any problems with asthma and its initial treatment are reviewed.

- Planning the prevention of acute exacerbations. Prevention against acute asthma attacks requires collaborative efforts from patients and healthcare workers. Firstly, patients should be encouraged to have long-term monitoring of asthma and stay on adequate medications. Secondly, patients should be educated on how to identify a worsening of their condition as early as possible. In this regard, the importance of pulmonary function testing should be particularly underlined, since a decline in lung function (typically as reflected by PEF) may precede any uncomfortable symptoms, and therefore prompt the patient to see a doctor earlier. Patients with acute exacerbations should be encouraged to seek medical attention quickly at healthcare institutions they usually visit. Those at high risk of asthma-related death require urgent care and closer attention. Those who have recovered from an asthma exacerbation should be advised to stay on regular and adequate maintenance treatment and avoid risk factors to prevent relapse.

Directions for future research

Although many clinical trials have shown that ICS/LABA-based treatment regimens can result in favorable clinical control and reduced future risks, the rates of asthma control in the real world are much lower than expected. Many factors may account for this, including poor patient compliance, inadequate treatment, heterogeneity in manifestations of asthma, and the yet incompletely understood pathogenesis of asthma. There is thus a dire need for perseverant insight with more basic research and clinical studies towards improving asthma control. For instance, a series of studies on airway remodeling and relevant therapeutic targets are on-going; in-depth studies on neutrophilic asthma, individualized treatment strategies and bronchial thermoplasty are expected to offer new promises for asthma control.

Appendix 1

Asthma Control Test™ (ACT)

- In the past 4 weeks, how much of the time did your asthma keep you from getting as much done at work, school, or home?

- All of the time

- Most of the time

- Some of the time

- A little of the time

- None of the time

- During the past 4 weeks, how often have you had shortness of breath?

- More than once a day

- Once a day

- Three to 6 times a week

- Once or twice a week

- Not at all

- During the past 4 weeks, how often did your asthma symptoms (wheezing, coughing, shortness of breath, chest tightness, or pain) wake you up at night or earlier than usual in the morning?

- Four or more nights a week

- Two to 3 nights a week

- Once a week

- Once or twice

- Not at all

- During the past 4 weeks, how often have you used your rescue medication (such as Albuterol)?

- Three or more times per day

- One or 2 times per day

- Two or 3 times per week

- Once a week or less

- Not at all

- How would you rate your asthma control during the past 4 weeks?

- Not controlled at all

- Poorly controlled

- Somewhat controlled

- Well controlled

- Completely controlled

A total point value of 25 means completely controlled; 20-24, well controlled; and <20, not well controlled.

Appendix 2

Asthma Control Questionnaire 5-item version (ACQ-5)

- On average, during the past week, how often were you woken up by your asthma during the night?

- Never

- Hardly ever

- A few times

- Several times

- Many times

- A great many times

- Unable to sleep because of asthma

- On average, during the past week, how bad were your asthma symptoms when you woke up in the morning?

- No symptoms

- Very mild symptoms

- Mild symptoms

- Moderate symptoms

- Quite severe symptoms

- Severe symptoms

- Very severe symptoms

- In general, during the past week, how limited were you in your activities because of your asthma?

- Not limited at all

- Very slightly limited

- Slightly limited

- Moderately limited

- Very limited

- Extremely limited

- Totally limited

- In general, during the past week, how much shortness of breath did you experience because of your asthma?

- None

- Very little

- Little

- Moderate amount

- Quite a lot

- A great deal

- Very great deal

- In general, during the past week, how much of the time did you wheeze?

- Not at all

- Hardly any of the time

- A little of the time

- Some of the time

- Lot of the time

- Most of the time

- All the time

An average score of <0.75 means completely controlled; 0.75-1.5, well controlled; and >1.5, uncontrolled.

Acknowledgements

This consensus document was translated from a Chinese version by Dr. Prof. Guangqiao Zeng and his colleagues, with permission and authorization from Prof. Jiang-Tao Lin. The translators aim to promote and distribute these guidelines to a wider international scientific audience, and declare no conflict of interest. Contributors of this consensus document are (sort by chapter): Jiang-Tao Lin (Department of Respiratory Medicine, China-Japan Friendship Hospital); Kai-Sheng Yin (Department of Respiratory Medicine, First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University); Chang-Zheng Wang (Department of Respiratory Medicine, Xinqiao Hospital, Third Military Medical University); Hua-Hao Shen (Department of Respiratory Medicine, Second Hospital of Zhejiang University); Xin Zhou (Department of Respiratory Medicine, First People’s Hospital, Shanghai Jiaotong University); Chun-Tao Liu (Department of Respiratory Medicine, West China Hospital of Sichuan University); Nan Su (Department of Respiratory Medicine, China-Japan Friendship Hospital); and Guo-Liang Liu (Department of Respiratory Medicine, China-Japan Friendship Hospital). This consensus document is endorsed by a panel of experts (in alphabetical order): Shao-Xi Cai (Department of Respiratory Medicine, Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University); Ping Chen (Department of Respiratory Medicine, General Hospital of Shenyang Military Region); Yi-Qiang Chen (Department of Respiratory Medicine, First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University); Mao Huang (Department of Respiratory Medicine, First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University); Ling-Fei Kong (Department of Respiratory Medicine, First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University); Jing Li (Guangzhou Institute of Respiratory Diseases); Jiang-Tao Lin (Department of Respiratory Medicine, China-Japan Friendship Hospital); Ao Liu (Department of Respiratory Medicine, General Hospital of Kunming Military Region); Chun-Tao Liu (Department of Respiratory Medicine, West China Hospital of Sichuan University); Rong-Yu Liu (Department of Respiratory Medicine, First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University); Xian-Sheng Liu (Department of Respiratory Medicine, Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology); Chen Qiu (Department of Respiratory Medicine, Shenzhen People’s Hospital); Hua-Hao Shen (Department of Respiratory Medicine, Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University); Nan Su (Department of Respiratory Medicine, China-Japan Friendship Hospital); Yong-Chang Sun (Department of Respiratory Medicine, Beijing Tongren Hospital, Capital Medical University); Huan-Ying Wan (Department of Respiratory Medicine, Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiaotong University); Chang-Zheng Wang (Department of Respiratory Medicine, Xinqiao Hospital, Third Military Medical University); Chang-Gui Wu (Department of Respiratory Medicine, Xijing Hospital, Fourth Military Medical University); Wen-Bing Xu (Department of Respiratory Medicine, Peking Union Hospital, Peking Union Medical College and Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences); Kai-Sheng Yin (Department of Respiratory Medicine, First Affiliated Hospital, Nanjing Medical University); Ya-Dong Yuan (Department of Respiratory Medicine, Second Affiliated Hospital of Hebei Medical University); and Wei-He Zhao (Department of Respiratory Medicine, Ningbo Second Hospital).

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Asthma Workgroup, Chinese Thoracic Society, Chinese Medical Association. Guidelines on the prevention and treatment of bronchial asthma: definition, diagnosis, treatment, and management. Chin J Tuber Respir Dis 2008;31:177-85.

- Global Initiative for Asthma. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. Available online: http://www.ginasthma.org/local/uploads/files/CINA-Report2011-May4.pdf

- National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Pocket guide for asthma management and prevention: a pocket guide for physicians and nurses. Philadelphia: Diane Publishing Company, 1995.

- Lai CK, Ko FW, Bhome A, et al. Relationship between asthma control status, the Asthma Control TestTM and urgent health-care utilization in Asia. Respirology 2011;16:688-97. [PubMed]

- Holgate ST, Price D, Valovirta E. Asthma out of control? A structured review of recent patient surveys. BMC Pulm Med 2006;6 Suppl 1:S2. [PubMed]

- Partridge MR, van der Molen T, Myrseth SE, et al. Attitudes and actions of asthma patients on regular maintenance therapy: the INSPIRE study. BMC Pulm Med 2006;6:13. [PubMed]

- FitzGerald JM, Boulet LP, McIvor RA, et al. Asthma control in Canada remains suboptimal: the Reality of Asthma Control (TRAC) study. Can Respir J 2006;13:253-9. [PubMed]

- Benkheder A, Bouacha H, Nafti S, et al. Control of asthma in the Maghreb: results of the AIRMAG study. Respir Med 2009;103 Suppl 2:S12-20. [PubMed]

- Peters SP, Jones CA, Haselkorn T, et al. Real-world Evaluation of Asthma Control and Treatment (REACT): findings from a national Web-based survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;119:1454-61. [PubMed]

- Bateman ED, Reddel HK, Eriksson G, et al. Overall asthma control: the relationship between current control and future risk. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010;125 600-8, 608.el-608.e6.

- Mancia G, Laurent S, Agabiti-Rosei E, et al. Reappraisal of European guidelines on hypertension management: a European Society of Hypertension Task Force document. J Hypertens 2009;27:2121-58. [PubMed]

- Liu LS, Writing Group of 2010 Chinese Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension. 2010 Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertension. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi 2011;39:579-615. [PubMed]

- Nathan DM, Buse JB, Davidson MB, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: A consensus algorithm for the initiation and adjustment of therapy: a consensus statement from the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2006;29:1963-72. [PubMed]

- Bateman ED, Bousquet J, Busse WW, et al. Stability of asthma control with regular treatment: an analysis of the Gaining Optimal Asthma controL (GOAL) study. Allergy 2008;63:932-8. [PubMed]

- Bai TR, Vonk JM, Postma DS, et al. Severe exacerbations predict excess lung function decline in asthma. Eur Respir J 2007;30:452-6. [PubMed]

- Kitch BT, Paltiel AD, Kuntz KM, et al. A single measure of FEVl is associated with risk of asthma attacks in long-term follow-up. Chest 2004;126:1875-82. [PubMed]

- Fuhlbrigge AL, Kitch BT, Pahiel AD, et al. FEV(1) is associated with risk of asthma attacks in a pediatric population. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001;107:61-7. [PubMed]

- O’Byrne PM, Reddel HK, Eriksson G, et al. Measuring asthma control: a comparison of three classification systems Eur Respir J 2010;36:269-76. [PubMed]

- Chen H, Gould MK, Blanc PD, et al. Asthma control, severity, and quality of life: quantifying the effect of uncontrolled disease. J Allergy Clin lmmunol 2007;120:396-402.

- Reddel HK, Jenkins C, Quirce S, et al. Effect of different asthma treatments on risk of cold-related exacerbations. Eur Respir J 2011;38:584-93. [PubMed]

- O’Byrne PM, Bisgaard H, Godard PP, et al. Budesonide/formoterol combination therapy as both maintenance and reliever medication in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171:129-36. [PubMed]

- Scicchitano R, Aalbers R, Ukeua D, et al. Efficacy and safety of budesonide/formoterol single inhaler therapy versus a higher dose of budesonide in moderate to severe asthma. Curr Med Res Opin 2004;20:1403-18. [PubMed]

- Kuna P, Peters MJ, Manjra AI, et al. Effect of budesonide/formoterol maintenance and reliever therapy on asthma exacerbations. Int J Clin Pract 2007;61:725-36. [PubMed]

- Bousquet J, Boulet LP, Peters MJ, et al. Budesonide/formoterol for maintenance and relief in uncontrolled asthma vs. high-dose salmeterol/fluticasone. Respir Med 2007;101:2437-46. [PubMed]

- Rabe KF, Atienza T, Magyar P, et al. Effect of budesonide in combination with formoterol for reliever therapy in asthma exacerbations: a randomised controlled, double-blind study. Lancet 2006;368:744-53. [PubMed]