European perspective in Thoracic surgery—eso-coloplasty: when and how?

Introduction

Colon interposition has been used since the beginning of the 20th century as a substitute for esophagus. Historically the first coloplasty was realised by Kelling in 1911, and the first successful use of a colon after esophagectomy in 1914 by Von Hacker (1,2). Afterwards colon became the organ of choice for esophageal replacement (3).

In the second part of the 20th century, the stomach was admitted as the first choice for reconstruction after esophagectomy, in particular if performed for esophageal cancer (4,5). The procedure is fast, safe, standardized, requires a single anastomosis and can be performed through a minimally invasive approach. Moreover, the stomach has a good vascularization, and presents a low leakage and necrosis rate, with good functional results (6,7).

Nowadays, colon interposition is mainly chosen as a second line treatment when the stomach cannot be used or for tumors of the upper esophagus or the hypopharynx where the length of the stomach is expected to be too short. Some centers reserve colonic interposition for young patients with benign disease with a long-life expectancy because of its relative good long-term functional outcomes (3,8-20).

This review aims at briefly defining “when” and “how” to perform a coloplasty.

Eso-colopasty: when?

Four situations can be considered where colon can be indicated for reestablishment of the digestive continuity after esophagectomy.

The stomach is not acceptable as a substitute

When the stomach is not suitable for the esophageal reconstruction, another substitute has to be considered. This situation can be seen in case of:

- Previous gastric surgery (metachronous cancer, history of peptic ulceration…);

- Failed gastric pull-up (extensive necrosis or intractable leakage…);

- Doubtful viability (caustic burn lesion) or if the gastric vascularization has been compromised during the surgery (11,15,17,21).

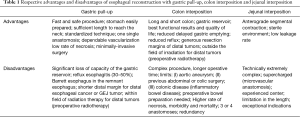

Two substitutes are available, either the colon or a jejunal graft. Compared to colon interposition, jejunal interposition is a more difficult procedure, dependent of the anatomy of the vascularization of the patient and needing an experienced team requiring most of the time a microvascular transposition to the supra aortic vessels (13,22-24). Advantages and disadvantages of each substitute are discussed in Table 1.

Full table

The stomach has to be resected for oncological reasons

When the patient presents a tumor of the gastro-esophageal junction (GEJ) classified Siewert III, a tumor with signet-cells or a mucinous adenocarcinoma, the stomach must be resected for oncologic reasons during the esophagectomy (8,11,15,17). This total esophago-gastrectomy is a validated option to insure the completeness of the resection (25,26). The colon is then used with a Roux-en Y loop.

The stomach is deliberately kept intact for functional outcomes

For young patients presenting end-stage esophageal disorders (achalasia) or complex benign diseases, an esophagectomy with colon interposition is sometimes indicated with the deliberate intention to conserve the stomach intact (27-29). In those cases, some authors suggest to keep intact the stomach because of the expected good functional outcome with the coloplasty. In this situation, a functional reservoir is created and the patient has less acid and bile reflux then when performing a gastric interposition. These two conditions are considered as two main factors in the quality of life of young patients with a long life expectancy and especially in a benign disease setting (9,16). This paradigm can be applied for patients who suffered from a caustic burn of the esophagus or for all indications of esophageal replacement for benign diseases: benign tracheal fistula, non malignant stenosis (caustic, peptic, post-radiation), post traumatic, end-stage functional disorders (10,14,19,20,30,31).

Pediatrics indications

In addition, specific indications for pediatric cases can be considered. There is no consensus on what constitutes the best substitute for the esophageal replacement in congenital diseases such as atresia, severe strictures after caustic burn injuries or after complex peptic stenosis (32,33). For atresia, when primary anastomosis is not possible, gastric interposition is most often the first choice. Colon interposition remains a possibility, offering good results with more than 50% of the patients asymptomatic in the long term (34-37).

Eso-coloplasty: how?

Several options are available when choosing colon interposition for esophageal replacement, depending of the vascularisation of the graft. Vascularisation is an essential step for the technical success of the surgery.

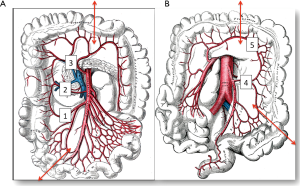

Vascular anatomy

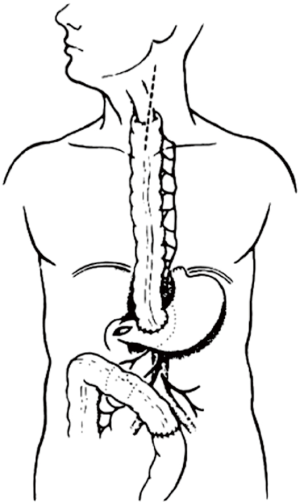

The colon vascularisation is divided in two parts, one coming from the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and the other one coming from the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA). This allows defining the right and the left colon grafts for colon interposition (Figure 1) (16,38). The right colon arterial vessels come from the SMA. It goes from the end of the ileon to the first two thirds of the transverse colon, passing by the right hepatic flexure. The SMA gives birth first to the ileo-colic arteries, rarely absent, then to the right colic artery and finally to the media colica. Those last two arteries can be absent in about 25% cases each. Moreover anastomoses between the vessels can be lacking in 5% of cases, resulting in the ischemia of the colon graft. The left colon vascularisation, going from the last third of the transverse colon to the sigmoid colon, comes from the inferior mesenteric artery. The left colonic grafts include short transplant using the transverse colon and long ones using both the transverse and the left colon. The marginal artery of Drummond is the anastomosis between the right colic vessels and the left colic vessels. This artery is irregular, as it can be missing in 25% to 75%, and interrupted at the left colic angle in 5% of cases. When the IMA is occluded, for example in case of previous aortic surgery or atherosclerosis, there is a growth of this marginal artery, which can mask bad vascularisation of a left colonic graft and lead to the failure of the subsequent colonic interposition.

Pre-operative management

Though the vascularisation of the colon is an important factor for a successful operation, pre-operative angiography of the colic vessels is not systematically performed. There is no study in the literature proving pre-operative angiography achieves better results as anatomical variations are dealt with intra-operatively (39,40). Thus, in our opinion, it should be indicated for selected patients: in cases of previous abdominal surgery with potential involvement of the colonic vessels, previous surgery of the abdominal aorta, or in case of lower extremity claudication.

A colonoscopy should be performed for patients over 45 years old, symptomatic or with a history of arteriosclerosis (3,11,16). The colonoscopy allows to observe the mucosal trophicity and to check the absence of chronic ischemia, cancer or diverticulosis.

Previous to the surgery a bowel preparation is performed for all patients. When oral feeding is still possible cathartics and an appropriate diet should be given. For other patients, either a jejunostomy allows the administration of the cathartics, or iterative water enemas are used.

Surgical technique

Surgical approaches

Several approaches can be used depending on the site of the proximal anastomosis and the need for a concomitant esophagectomy, either for a cancerous disease or a benign one. The whole procedure can be performed through a left thoraco-phreno-laparotomy in case of a short colonic transplant with an intra-thoracic anastomosis. The majority of colon interpositions are performed through a midline laparotomy for preparation of the colon associated with a left cervicotomy for the proximal anastomosis for long colonic transplant. If a concomitant esophagectomy is needed, it can be performed either through a trans-hiatal approach, a right open thoracotomy or in the recent years through a right thoracoscopy (41).

The choice of the graft and its preparation

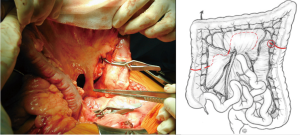

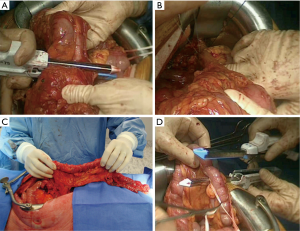

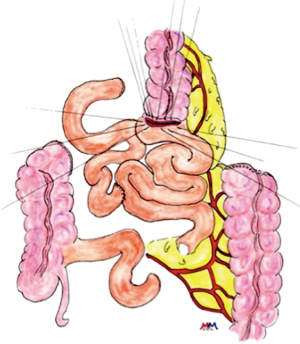

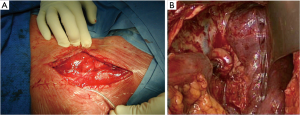

The first step of the procedure consists in the choice of an adequate transplant, ideally used in an iso-peristaltic position. The transverse colon, branched on the middle colic artery can be used as a short colic transplant, or as a long one if vascularized with left colonic vessels, birthed by the IMA. In our opinion, the transplant of choice is a left transverse colonic transplant, the arterial flow coming from the left vessels, and branched in an iso-peristaltic way (3,16,42). This technique provides enough length to the thorax or the neck with an excellent vascular supply in an isoperistaltic position. The colon is completely mobilized, from the caecum to the right than left flexures, and finally to the pelvic rim and the sigmoid colon. Once the colon can be fully moved, the arterial vascularisation is identified using transillumination. The left colonic vessels are seen, forming an arch from the descending colon up to the left flexure under the spleen (Figures 2,3).

With atraumatic vascular clamps, the right colic artery, the colica media and the collateral arcades at both extremities are occluded (Figure 4). This allows to check the correct arterial outflow in the colonic transplant, and to detect a previously masked occlusion of the IMA. During the same time, the venous outflow is also checked, verifying that there is no congestion. This whole step must be performed for at least 10 minutes (Figure 5).

Once the good arterial and venous vascularization have been confirmed, the proximal colon is transected. The proximal arcade is divided, but the distal one is preserved. The colica media is divided also, totally for long transplants, or only the left branch for short ones. The length of the transplant needed is checked and finally the distal colon is transected also. The colonic transplant is than free on both ends, pedicled on the left colonic vessels (Figure 6).

Some teams use preferentially the terminal ileum and right colon as a long transplant. The steps and the strategy are the same, except that the main pedicle is the middle colic artery. The integrity of the artery is confirmed after clamping the ileo-colic artery, the right colic artery and the marginal arteries (15,17,45). The transverse colon in an isoperistaltic way, using the right colic artery or the middle colic artery as a main vessel, can be used as last resort. But the long-term outcome is disappointing, with bad functional results and regurgitations (16).

The route of reconstruction

Whatever the colonic transplant used, either because of the team preferences or for surgical reasons, the route through which it will be positioned must be chosen with care. For long colonic transplants, the route depends essentially of an associated esophagectomy during the surgical procedure. The goal of this step is to achieve as straight a position as possible for the transplant, in order to avoid late complications such as redundancy (11,16). Whenever it is possible, the posterior mediastinum should be chosen (46,47). When not possible, either because the posterior mediastinum is not available (for example if the esophagus is left in place), or because a local recurrence or radiotherapy are expected, other routes can be chosen. Most often, a retrosternal position will be used, through the compression of the transplant can be bothering at the upper thoracic inlet (Figure 7). Some authors have suggested resecting the left part of the manubrium and the clavicle (49). To avoid kinking of the transplant, care should be taken not to open both pleura. In case of previous sternotomy, or radiation of the thorax, the retrosternal route can be unavailable. The transplant can then be positioned through a sub-cutaneous route (50). This route also has been chosen successfully as a first choice for some teams. The use of tissue expanders has helped to avoid the downfall of this route, which is too tight tunnels, causing post-operative dysphagia. Finally the colon graft can be positioned through a trans-pleural route (51). Though this route should be avoid if possible, as it can easily lead to dilatation of the transplant and colon redundancy.

Digestive anastomoses

Once the colon transplant is correctly positioned from the abdomen to the neck or to the thorax, the last step of the operation lays in performing the anastomoses. If the stomach was preserved, three anastomoses are needed: the eso-colic anastomosis or eso-ileal if a right colon was chosen, the colo-gastric anastomosis, and finally the colo-colic one. When a gastrectomy is performed, the colo-gastric anastomosis is replaced with a colo-jejunostomy and a jejuno-jenal anastomosis (Roux-en-Y loop) (Figures 8,9). The eso-colic anastomosis may be hand-sewn or mechanical with a circular stapling device. It must be performed first to ensure that the colon transplant has an optimal length and prevent redundancy (11,49,52). We usually perform a hand-sewn anastomosis, with two running sutures of absorbable 3.0 suture (Figures 10,11). Intra-thoracic anastomoses can be performed mechanically. The colo-gastric anastomosis is best done at the posterior side of the antrum and is associated with a pyloroplasty. We perform an end-to-side anastomosis, with two running sutures of absorbable 3.0 stitches.

In order to improve outcomes of colon interposition, an additional step using microsurgery has been introduced since 2003 (54). “Superdrainage” consists in performing a venous anastomosis in order to avoid congestion of the transplant. For right colic transplants it can be performed between the ileo-colic vein or the terminal ileal vein and the anterior or exterior jugular vein, or the internal thoracic vein (17,55). On the other hand, “supercharged colic interposition” is an arterial anastomosis to avoid ischemic necrosis of the graft. For right colic transplants it is performed between the internal thoracic and the ileo-colic arteries (17). For left ones between the stump of the sigmoid artery and the superior thyroid artery or the facial artery (56,57). Several publications report the successful use of those techniques, though the number of procedures must be increased to truly evaluate the impact of superdrainage and supercharged on colon interposition outcomes (15,17,54-57). Furthermore, the length of the procedures is greatly increased and must be taken into account in an already difficult and long operation.

Discussion

Colon interposition is a complex operation, with specific indications. Over time the indications of colonic interposition have changed. Colon interposition is nowadays reserved for selected patients with esophageal cancer when the stomach is unavailable or has to be resected or for benign diseases of the esophagus (3,8-20).

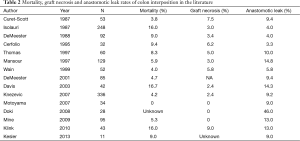

In the literature, the reported post-operative mortality of the procedure ranges from 0 to more than 16%, with an associated risk of graft necrosis going from 0 to 10%, and anastomosis leak from 0 to 15% (Table 2) (3,8,9,11-15,47,58-63). Risk factors for conduit ischemia such as diabetes, cardio-vascular diseases and COPD have been identified, and should be optimized pre-operatively (64). In addition, for anastomotic leak, neo-adjuvant therapy and conduit ischemia have also been described as risk factors.

Full table

The surgical management of a failed colon transplant in the early post-operative period can be challenging. When faced with a colon graft necrosis, as much viable conduct should be preserved in view of future reconstruction (49). Associated measures such as control of the sepsis, limitation of the inflammation surrounding the bed of the conduct, and performing an optimal nutritional resuscitation, are mandatory to improve the outcome.

In the early post-operative period, patients complain of dysphagia, diarrhea, reflux and dumping syndrome. Symptoms improve in the post-operative course (15). Late complications are frequent and can lead to further invasive treatments. Thus redundancy of the colon transplant is reported in 0 to 40% of cases and can lead to re-intervention, though the exact number of revision surgery is unknown (9,11,12,14,47,52,60,65). Anastomosis stricture is found in 0 to 40% of cases, and is most of the time successfully managed with endoscopic dilatations (3,9,11,12,14,47,52,59,60,65). It is increased for over-weight patients (continuous variable) and patients with a history of conduit ischemia and/or anastomotic leak (64). Chronic aspirations are needed in less than 10% of patients, and complications such as colo-cutaneous or colo-bronchic fistulaes, and secondary cancer of the transplant remain unusual (66-68).

In the literature, the reported quality of life after colon interposition is usually good (3,14,37,69-71). Though gastric pull-up after esophagectomy has been reported to have good results, the main complication in the long term is the presence of biliary reflux and secondary reflux disease in the conduit (7,72). For benign diseases, performing a vagal-sparing esophagectomy allows to conserve a fully innervated stomach and gastro-intestinal tract. Thus, there is no delayed stomach emptying, and the usual symptoms present after gastric pull-up decrease. If the resection of the vagus nerves is needed, the delayed emptying of the stomach can be prevented with a partial gastrectomy (73). In the long term, colon interposition allows a better quality of life, with less esophagitis (74). Notwithstanding the complexity of the procedure, this is why colon interposition is chosen over gastric pull-up for young patients with a long life expectancy needing an esophagectomy for benign diseases.

Conclusions

The colon is a good substitute for the esophagus in selected situations, with several options available for the reconstruction. The procedure can be long and complex, with three or four anastomoses needed. Even if there is a high rate of redundancy in the long-term with an eventual need for re-intervention, the colon provides durable and satisfactory alimentary comfort, with an acceptable operative risk.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Kelling GE. Oesophagoplastik mit Hilfe des Querkolons. Zentralbl Chir 1911;38:1209-12.

- Von Hacker V. Uber Oesophagoplastik in Allgemeinen under uber den Ersatz der Speiserohre durch antethorakle Hautdickdarmschlauchbildung im Besonderen. Arch Klin Chir 1914;105:973.

- Thomas P, Fuentes P, Giudicelli R, et al. Colon interposition for esophageal replacement: current indications and long-term function. Ann Thorac Surg 1997;64:757-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Akiyama H, Miyazono H, Tsurumaru M, et al. Use of the stomach as an esophageal substitute. Ann Surg 1978;188:606-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sugarbaker DJ, DeCamp MM. Selecting the surgical approach to cancer of the esophagus. Chest 1993;103:410S-414S. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McLarty AJ, Deschamps C, Trastek VF, et al. Esophageal resection for cancer of the esophagus: long-term function and quality of life. Ann Thorac Surg 1997;63:1568-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Greene CL, DeMeester SR, Worrell SG, et al. Alimentary satisfaction, gastrointestinal symptoms, and quality of life 10 or more years after esophagectomy with gastric pull-up. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014;147:909-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Isolauri J, Markkula H, Autio V. Colon interposition in the treatment of carcinoma of the esophagus and gastric cardia. Ann Thorac Surg 1987;43:420-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Curet-Scott MJ, Ferguson MK, Little AG, et al. Colon interposition for benign esophageal disease. Surgery 1987;102:568-74. [PubMed]

- Little AG, Naunheim KS, Ferguson MK, et al. Surgical management of esophageal strictures. Ann Thorac Surg 1988;45:144-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- DeMeester TR, Johansson KE, Franze I, et al. Indications, surgical technique, and long-term functional results of colon interposition or bypass. Ann Surg 1988;208:460-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cerfolio RJ, Allen MS, Deschamps C, et al. Esophageal replacement by colon interposition. Ann Thorac Surg 1995;59:1382-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mansour KA, Bryan FC, Carlson GW. Bowel interposition for esophageal replacement: twenty-five-year experience. Ann Thorac Surg 1997;64:752-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Knezević JD, Radovanović NS, Simić AP, et al. Colon interposition in the treatment of esophageal caustic strictures: 40 years of experience. Dis Esophagus 2007;20:530-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mine S, Udagawa H, Tsutsumi K, et al. Colon interposition after esophagectomy with extended lymphadenectomy for esophageal cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 2009;88:1647-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thomas PA, Gilardoni A, Trousse D, et al. Colon interposition for oesophageal replacement. Multimed Man Cardiothorac Surg 2009;2009:mmcts.2007.002956.

- Hamai Y, Hihara J, Emi M, et al. Esophageal reconstruction using the terminal ileum and right colon in esophageal cancer surgery. Surg Today 2012;42:342-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morita M, Saeki H, Ito S, et al. Technical improvement of total pharyngo-laryngo-esophagectomy for esophageal cancer and head and neck cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2014;21:1671-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ezemba N, Eze JC, Nwafor IA, et al. Colon interposition graft for corrosive esophageal stricture: midterm functional outcome. World J Surg 2014;38:2352-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kitajima T, Momose K, Lee S, et al. Benign esophageal stricture after thermal injury treated with esophagectomy and ileocolon interposition. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:9205-9. [PubMed]

- Cheng BC, Xia J, Shao K, et al. Surgical treatment for upper or middle esophageal carcinoma occurring after gastrectomy: a study of 52 cases. Dis Esophagus 2005;18:239-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Baker CR, Forshaw MJ, Gossage JA, et al. Long-term outcome and quality of life after supercharged jejunal interposition for oesophageal replacement. Surgeon 2015;13:187-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gaur P, Blackmon SH. Jejunal graft conduits after esophagectomy. J Thorac Dis 2014;6 Suppl 3:S333-40. [PubMed]

- Ninomiya I, Okamoto K, Oyama K, et al. Feasibility of esophageal reconstruction using a pedicled jejunum with intrathoracic esophagojejunostomy in the upper mediastinum for esophageal cancer. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014;62:627-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Piessen G, Messager M, Leteurtre E, et al. Signet ring cell histology is an independent predictor of poor prognosis in gastric adenocarcinoma regardless of tumoral clinical presentation. Ann Surg 2009;250:878-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Messager M, Lefevre JH, Pichot-Delahaye V, et al. The impact of perioperative chemotherapy on survival in patients with gastric signet ring cell adenocarcinoma: a multicenter comparative study. Ann Surg 2011;254:684-93; discussion 693. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Duranceau A, Liberman M, Martin J, et al. End-stage achalasia. Dis Esophagus 2012;25:319-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Glatz SM, Richardson JD. Esophagectomy for end stage achalasia. J Gastrointest Surg 2007;11:1134-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Watson TJ. Esophagectomy for end-stage achalasia. World J Surg 2015;39:1634-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boukerrouche A. Left colonic graft in esophageal reconstruction for caustic stricture: mortality and morbidity. Dis Esophagus 2013;26:788-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Radovanović N, Simić A, Kotarac M, et al. Colon interposition for pharyngoesophageal postcorrosive strictures. Hepatogastroenterology 2009;56:139-43. [PubMed]

- Loukogeorgakis SP, Pierro A. Replacement surgery for esophageal atresia. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2013;23:182-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gallo G, Zwaveling S, Groen H, et al. Long-gap esophageal atresia: a meta-analysis of jejunal interposition, colon interposition, and gastric pull-up. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2012;22:420-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Spitz L. Esophageal replacement: overcoming the need. J Pediatr Surg 2014;49:849-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rintala RJ, Sistonen S, Pakarinen MP. Outcome of esophageal atresia beyond childhood. Semin Pediatr Surg 2009;18:50-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ron O, De Coppi P, Pierro A. The surgical approach to esophageal atresia repair and the management of long-gap atresia: results of a survey. Semin Pediatr Surg 2009;18:44-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Burgos L, Barrena S, Andrés AM, et al. Colonic interposition for esophageal replacement in children remains a good choice: 33-year median follow-up of 65 patients. J Pediatr Surg 2010;45:341-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sakorafas GH, Zouros E, Peros G. Applied vascular anatomy of the colon and rectum: clinical implications for the surgical oncologist. Surg Oncol 2006;15:243-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schröder W, Zähringer M, Stippel D, et al. Does celiac trunk stenosis correlate with anastomotic leakage of esophagogastrostomy after esophagectomy? Dis Esophagus 2002;15:232-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McDermott S, Deipolyi A, Walker T, et al. Role of preoperative angiography in colon interposition surgery. Diagn Interv Radiol 2012;18:314-8. [PubMed]

- Nguyen TN, Hinojosa M, Fayad C, et al. Laparoscopic and thoracoscopic Ivor Lewis esophagectomy with colonic interposition. Ann Thorac Surg 2007;84:2120-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maguire D, Collins C, O'Sullivan GC. How I do it--Replacement of the oesophagus with colon interposition graft based on the inferior mesenteric vascular system. Eur J Surg Oncol 2001;27:314-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gust L, Ouattara M, Coosemans W, et al. Mobilisation of the colon. Asvide 2016;3:210. Available online: http://www.asvide.com/articles/966

- Gust L, Ouattara M, Coosemans W, et al. Clamping of the colic arterial vessels. Asvide 2016;3:211. Available online: http://www.asvide.com/articles/967

- Matsumoto H, Hirai T, Kubota H, et al. Safe esophageal reconstruction by ileocolic interposition. Dis Esophagus 2012;25:195-200. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oida T, Mimatsu K, Kano H, et al. Anterior vs. posterior mediastinal routes in colon interposition after esophagectomy. Hepatogastroenterology 2012;59:1832-4. [PubMed]

- Motoyama S, Kitamura M, Saito R, et al. Surgical outcome of colon interposition by the posterior mediastinal route for thoracic esophageal cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 2007;83:1273-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gust L, Ouattara M, Coosemans W, et al. The colic transplant is brought to the neck through a retro-sternal route. Asvide 2016;3:212. Available online: http://www.asvide.com/articles/968

- de Delva PE, Morse CR, Austen WG Jr, et al. Surgical management of failed colon interposition. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2008;34:432-7; discussion 437. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kent MS, Gayle L, Hoffman L, et al. A new technique of subcutaneous colon interposition. Ann Thorac Surg 2005;80:2384-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Davydov M, Stilidi I, Bokhyan V. Intrapleural colon interposition in gastric carcinoma patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2001;20:1063-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Strauss DC, Forshaw MJ, Tandon RC, et al. Surgical management of colonic redundancy following esophageal replacement. Dis Esophagus 2008;21:E1-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gust L, Ouattara M, Coosemans W, et al. Hand-sewn cervical eso-colic anastomosis. Asvide 2016;3:213. Available online: http://www.asvide.com/articles/969

- Gorman JH 3rd, Low DW, Guy TS 4th, et al. Extended left colon interposition for esophageal replacement using arterial augmentation. Ann Thorac Surg 2003;76:933-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Saeki H, Morita M, Harada N, et al. Esophageal replacement by colon interposition with microvascular surgery for patients with thoracic esophageal cancer: the utility of superdrainage. Dis Esophagus 2013;26:50-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lu HI, Kuo YR, Chien CY. Extended left colon interposition for pharyngoesophageal reconstruction using distal-end arterial enhancement. Microsurgery 2008;28:424-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shirakawa Y, Naomoto Y, Noma K, et al. Colonic interposition and supercharge for esophageal reconstruction. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2006;391:19-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- DeMeester SR. Colon interposition following esophagectomy. Dis Esophagus 2001;14:169-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wain JC, Wright CD, Kuo EY, et al. Long-segment colon interposition for acquired esophageal disease. Ann Thorac Surg 1999;67:313-7; discussion 317-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Davis PA, Law S, Wong J. Colonic interposition after esophagectomy for cancer. Arch Surg 2003;138:303-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Doki Y, Okada K, Miyata H, et al. Long-term and short-term evaluation of esophageal reconstruction using the colon or the jejunum in esophageal cancer patients after gastrectomy. Dis Esophagus 2008;21:132-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Klink CD, Binnebösel M, Schneider M, et al. Operative outcome of colon interposition in the treatment of esophageal cancer: a 20-year experience. Surgery 2010;147:491-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kesler KA, Pillai ST, Birdas TJ, et al. "Supercharged" isoperistaltic colon interposition for long-segment esophageal reconstruction. Ann Thorac Surg 2013;95:1162-8; discussion 1168-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Briel JW, Tamhankar AP, Hagen JA, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for ischemia, leak, and stricture of esophageal anastomosis: gastric pull-up versus colon interposition. J Am Coll Surg 2004;198:536-41; discussion 541-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jeyasingham K, Lerut T, Belsey RH. Functional and mechanical sequelae of colon interposition for benign oesophageal disease. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1999;15:327-31; discussion 331-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Harvey JG, Kettlewell MG. An unusual complication of colonic interposition for oesophageal replacement. Thorax 1979;34:408-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhao X, Sandhu B, Kiev J. Colobronchial fistula as a rare complication of coloesophageal interposition: a unique treatment with a review of the medical literature. Am Surg 2005;71:1058-9. [PubMed]

- Tranchart H, Chirica M, Munoz-Bongrand N, et al. Adenocarcinoma on colon interposition for corrosive esophageal injury: case report and review of literature. J Gastrointest Cancer 2014;45 Suppl 1:205-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Metzger J, Degen L, Beglinger C, et al. Clinical outcome and quality of life after gastric and distal esophagus replacement with an ileocolon interposition. J Gastrointest Surg 1999;3:383-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cense HA, Visser MR, van Sandick JW, et al. Quality of life after colon interposition by necessity for esophageal cancer replacement. J Surg Oncol 2004;88:32-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Greene CL, DeMeester SR, Augustin F, et al. Long-term quality of life and alimentary satisfaction after esophagectomy with colon interposition. Ann Thorac Surg 2014;98:1713-9; discussion 1719-20.

- D'Journo XB, Martin J, Ferraro P, et al. The esophageal remnant after gastric interposition. Dis Esophagus 2008;21:377-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Demeester TR. Esophageal Replacement With Colon Interposition. Operative Techniques in Cardiac & Thoracic Surgery. A Comparative Atlas, 1997;2:73-86.

- Yildirim S, Köksal H, Celayir F, et al. Colonic interposition vs. gastric pull-up after total esophagectomy. J Gastrointest Surg 2004;8:675-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]