肺癌中应用的现代诊断和治疗介入放射学

引言

影像学在原发性肺癌的各学科研究中发挥着重要作用,对肿瘤诊断、肿瘤的定位、特点和分期,为制定治疗计划而获取相关淋巴结、血管和支气管的解剖结构影像,以及异时性肿瘤的治疗疗效和发生发展的检测等方面是非常必要的。原发性肺癌影像引导的治疗可以在一些特定的患者中实施。这篇文章回顾了目前用于肺癌评估的影像技术,并探讨了用于组织病理诊断和肿瘤局部治疗的影像引导的经皮穿刺技术。而对于肺癌的筛查这篇文章本文不进行讨论。

各种影像技术

计算机断层扫描(CT)是对可疑或者已证实确诊的肺癌患者进行初步评估选择的影像技术。正电子发射断层扫描(PET)/CT是确定原发性肺癌分期的最精确的影像技术。磁共振(MIR)成像技术在评估上腔沟(肺上沟瘤)肿瘤,胸壁、纵隔和脊髓的可疑恶性侵袭时是非常有用的。目前,确认肺癌分期推荐的影像方法是胸部CT扫描和从头颅到大腿中部的PET/CT[1]。

计算机断层扫描

先进的CT扫描机通过改进的照射剂量模式,在持续几秒的单次屏息期间内可以对整个胸部进行高分辨和综合的评估,从而产生可以对肺癌进行详尽的解剖和功能方面评估的等同性数据集合。使用自动管电流调制和三维重建技术的应用可降低照射剂量,这使得CT检查能够使用较低的剂量获得同样质量的影像资料,或者是同样的照射剂量而获得质量更高的影像资料[2,3]。较小的肺癌病灶的检出率的改善提高依赖于图像的快速采集和新的可视化技术。快速采集影像资料减少了呼吸和心脏运动产生的伪影,而且对肺结节有了更精确的描述,尤其是在肺底和心脏旁的肺组织处。新的可视化技术,例如最强投影、容积再现、立体图像展示和计算机辅助检测,都增强提高了肺癌的检出率,检测并能使阅片者区分血管和肺小结节[4]。等同性数据集合的获取使多维重建更容易实现,其中包括血管和支气管解剖结构的高分辨率血管造影和三维重建,这为手术和经皮穿刺的干预等措施提供了便利。

分期

尽管CT技术最近有了进展,运用CT检查进行肺癌分期仍然不是最优的检查手段,但却是例行做的检查,因为对于局限期T1和T2肿瘤,CT仍然是比较好的诊断手段,并能简单描述T3和T4肿瘤,用以指导选择最佳淋巴结及并对其进行的有创的检查技术,并且当出现明确的远处转移时允许患者接受非手术治疗。肺癌诊断分期时,CT的局限性包括早期纵隔和胸壁侵袭的精确检测,纵隔分期以及胸腔外小的转移灶的检测。关于局部肿瘤范围、分化,T3和T4具有重要的临床意义,因为其决定肿瘤是否需要完全切除以及手术方案[5]。使用薄层CT并没有明显提高胸膜壁层恶性侵袭的检测率。一项使用4排探测器CT对90位患者进行的研究,通过对胸壁侵袭的检测,显示其敏感性、特异性和精确性分别为42%、100%和83%[6]。另一项使用4排探测器CT的小型研究显示,检测胸壁侵袭时使用多维重建技术能提高CT的敏感性、特异性和精确性分别至86%、96%和95%[7]。关于淋巴结恶性侵润,最近一项meta分析显示CT检出率较差,敏感性和特异性分别是55%和81%;横向CT扫描影像上短径≤1cm为正常大小淋巴结是普遍被接受的定义,在检测纵隔淋巴结是否存在恶性侵润时,,这个标准同时可用来区分良恶性淋巴结[8]。这些结果显示单凭淋巴结大小的标准精确检测淋巴结是否转移是不足够的,因为已发生转移的正常大小的淋巴结会被遗漏掉,而且病因学上增大的淋巴结可能是反应或增生性的。最近的研究表明检测肺癌转移的淋巴结时,淋巴结其形态学和CT增强模式的评估能够提高CT的精确性[9,10]。对于远处转移,在检测肺外转移灶方面时CT不如PET/CT, CT的精确性为88%,而PET/CT为97%[11]。据我们所知,并没有研究使用超过16排探测器CT扫描精确检测来确定肺癌分期。

治疗后的评估和监测

目前,对于已确诊的肺癌患者,其最佳随访和检测程序方案并没有形成共识。而对有治愈倾向且经过治疗的非小细胞肺癌(NSCLC)患者,CT已被推荐为常规的评估和检测手段;对于没有经过治疗的无症状的进展期肺癌患者,没有推荐的常规影像检测方法[12-14]。治疗反应的CT评估用CT来评估肿瘤对治疗的反应,常常依赖于肿瘤和结节的形态学改变。然而,形态学并不是评估治疗早期反应的良好指标,肿瘤大小减小拖延延缓或者异常增加可能被证实是一个阳性反应[15]。CT对治疗后检测是有效的。一项研究表明CT在新发肺癌中检测出率为93%,而在另一项超过1000例患者的队列研究中发现早期NSCLC手术切除之后,CT检测复发率为61%[16]。

新进展

CT技术的最新进展允许研究评估肺癌的新方法,包括结节容积、结节灌注分析、双能量应用和计算机辅助检测。通过评估结节容积对肺结节的定量分析,可以使用半自动或者自动分段工具,其可以对结节的稳定性或者进展情况进行评估。肺结节的生长率是恶性程度的一个预测指标,而容积分析可以用来预测肿瘤对治疗的反应[17]。为了明确病灶的恶性可能以及更早确定相对于肿瘤大小上的形态改变其对治疗的反应,结节的C T灌注分析或许可以更好描述结节的特点[18,19]。当相对吸收值低于30亨氏单位(HU)时,恶性可能性就较低[20]。双能量CT扫描是一种可以将碘与其他材料例如软组织和骨质区分的技术,原理是由于碘具有更强的光电吸收特点[21]。使用增强CT后,这个方法可使肿物增强的程度和模式可视化。一项研究表明,肺内结节增强的程度能用来区分良恶性肿瘤,且其敏感性、特异性和精确度分别为92%、70%和82%[22]。在另一项研究中,在NSCLC患者中,胸内结节的最大碘衰竭和SUVmax之间的存在中度相关,但是在小细胞肺癌患者中他们之间的关系较弱[23]。作者认为NSCLC中的这种中度相关性可以用确诊恶性结节所做的PET的适度特异性来解释,而相比SCLC和NSCLC相关性上存在的差异,主要是由于肿瘤的生物学存在差异,例如血管生成能力的不同。

正电子发射断层摄影术

单发肺结节

F-18脱氧葡萄糖(FDG)PET通过描绘肺结节的特点进而区分良恶性病变,是一种非常有用的技术。两项meta分析表明,FDG-PET诊断恶性肺结节的敏感性和特异性分别可达96%和80%[24,25]。PET阳性结果的意义依赖于临床背景及肉芽肿性和感染性疾病的发病率,他们被认为是PET检查假阳性的原因。由于部分容积效应或者呼吸动度的影响,假阴性结果发生于小结节(<10 mm)中或者在某些低FDG亲和力的肺恶性肿瘤的亚型中,例如原位肺腺癌。在实践层面,PET阳性的研究常提示需要活组织切片检查或介入检查保证得以病理确诊[26],然而PET阴性的研究或许允许保守方法检查以及避免不必要的侵入性检查[27]。证据表明在诊断孤立的肺结节时,FDG-PET是一种经济有效的检查[28,29]。

分期

PET是评价肺癌结节和远处转移最精确的影像检查方法,对治疗计划的制定也是非常关键的。诸多临床病理研究发现,对纵隔结节性疾病的分期,PET比CT检查更精确,其中有两项meta分析结果显示PET的敏感性和特异性分别为79%~85%和90%~91%,而CT的则分别为60%~61%和77%~79%[30,31]。使用PET/CT后,结节评价的精确性进一步提高,而且对于早期疾病的纵隔评价具有较好的阴性预测值,约为91%[32,33]。尽管PET/CT在结节分期方面具有较高的精确性,但仍然存在明显的假阳性率,而且在较大(>1 cm)的结节中更普遍,这往往是由于反应性或者肉芽肿性疾病导致的[34]。随着微创获取纵隔结节样本技术的提高,例如支气管内超声和内镜超声的使用,对于可能治愈的疾病,在拒绝给对患者手术之前,获得PET阳性结节的病理诊断是非常重要的[35,36]。PET也是评价肺癌远处转移的影像检查手段,因为它可以全身显像,并能很好的凸显肿瘤,同时对骨和软组织转移也有极佳的检测率[37-39]。常规CT和放射性核素骨显像已确定分期的疾病,PET检查对未识别出存在远处转移病灶能很好的诊断。一项研究表明,使用PET诊断远处转移的检出率对于Ⅰ、Ⅱ和Ⅲ期仅分别为7.5%、18%和24%[40]。使用常规影像检查进行分期且认为可以手术的患者,其中有20%在PET检查后发现不能手术,PET被认为是在进行根治性治疗之前避免无用的手术干预的重要手段[41,42]。PET/CT已经显示在检测远处病灶时优于单独使用PET或者CT,主要是因为PET/CT能够获得解剖相关性,减低正常结构由于生理吸收而造成的PET的假阳性结果[43]。最近一项meta分析结果显示,检测骨转移时PET/CT明显优于PET、MR显像和放射性核素骨显像, PET/CT汇集的敏感性和特异性分别是92%和98%[44]。鉴于FDG在脑中吸收率高造成的高背景,FDG-PET并不是排除脑转移最佳的影像诊断方法,当出现临床表现时,应当使用MR显像评价[45]。PET/CT提供的结构和功能信息也促使选择关键能使人对有针对性的病灶进行组织活检,以获得病理确诊疾病。使用PET和PET/CT对NSCLC分期[46-48]是非常经济有效的,最近的一项随机临床试验显示每个患者节省了899欧元,并避免了胸廓切开术需要花费的4495欧元[49]。在要进行手术和根治性放疗的患者中,PET分期和存活之间也有很强的相关性,暗示PET提供了重要的预后信息[50,51]。

放疗计划制定

对于被认为可治愈或者可进行根治性放疗的局部进展期NSCLC患者,已发现FDG-PET和PET/CT在选择患者和确定靶区体积中发挥关键作用。根治性放疗用于存在局部肿瘤有治愈可能但不能手术的患者,在没有远处转移时,高剂量放疗可以完全包绕病灶[52]。许多前瞻性研究发现,在很可能进行根治性放疗的患者中使用PET检查后,约25%~30%的患者不适合进行根治性放疗,因为他们存在常规影像检查不能显示的进展性病灶[53-55]。PET辅助的放射治疗体积等高线更为精确,而且与常规治疗制定的体积明显不同,在超过30%的患者中发现放疗体积发生了变化[53,56,57]。PET/CT辅助的根治性放疗生存获益也更多。在一项研究中,发现PET/CT辅助的根治性放疗的IIIA期患者的4年生存率为32%,这优于CT辅助的根治性放疗的结果[58]。

治疗后评价

一项73例患者的前瞻性研究对比了FDG-PET和CT两者对NSCLC经过根治性放疗和同步放化疗后的反应评价,结果显示对PET的完全反应者(34例)相比CT(10例)明显要多。PET反应比CT反应在预测生存时间时更有价值,并且是对于在多因素分析时与生存时间唯一相关的预后因素[59]。最近一篇文章也报道,NSCLC标准治疗后高代谢肿瘤体积是一项独立的较差的预后因素[60]。对经过诱导化疗的NSCLC患者,FDG-PET也被发现可以提供重要的预后反应的评价。在一项31例Ⅲ期无法切除的疾病的前瞻性研究中,发现对PET的完全反应要比CT的更加精确,而且PET显示了在较长时间内与进展和总生存率有更明显的关联[61]。FDG-PET能提供更好的预后信息,在诱导化疗优于手术切除或者同步放化疗的治疗方案中也被报道,而且在治疗方案的选择和计划制定中PET或许也发挥着作用[62,63]。

磁共振成像

现代MR设备已经克服了其最初肺成像时由于空气软组织界面产生的磁场不均匀性的问题,以及诊断成像时与心脏和呼吸运动有关造成的伪影形成的问题。MR在肺癌的诊断、分期、放疗计划制定和治疗后评价等方面的作用还没有完全发挥出来,且仅有几个中心在深入研究。使用MR检测大于5 mm的肺肿瘤及非钙化病灶的敏感性、特异性、阳性预测值和阴性预测值均接近100%[64]。因此,MR能够用于肺癌的筛查,但是据我们所知,并没有前瞻性试验研究MR此方面的应用[65,66]。弥散加权像MR成像能用来预测肺部病灶的良恶性。一项66例患者前瞻性研究显示DWI诊断恶性病灶的敏感性、特异性和阳性预测值分别为95%、73%和87%[67]。

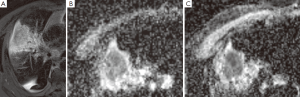

目前的临床实践中,由于MR具有较好的软组织对比分辨率,因此MR成像主要用于肺癌可疑胸壁和纵隔侵犯的评估。MR和FDG-PET/CT的对比研究显示两种技术对NSCLC分期的价值是相当的[68-70]。MR侧重于检测脑和肝转移病灶,而PET/CT对于确定结节分期更有优势。最近一项前瞻性研究表明,DWI的MR成像在NSCLC的检测和结节评估方面要比PET/CT更有优势[71]。MR也可以用来区分存活肿瘤和坏死肿瘤及肺不张,在放疗计划制定方面也发挥作用[72]。治疗后肿瘤的反应可以使用MR技术检测,例如磁化传递、依赖MR的血氧水平以及灌注和弥散成像。动态对比增强灌注成像可以评价肿瘤血管形成,也能预测NSCLC患者的化疗反应,但是它在检测抗血管治疗方面的作用还没有证实[73]。MR灌注成像也能用来预测术后肺功能[74]。关于DWI,表面弥散系数(ADC)衡量组织中水分子的弥散程度。细胞肿胀或者皱缩可以通过ADC值得变化反映出来。总之,治疗30天内肿瘤ADC值最初会出现降低(图1),而治疗随后的30天肿瘤ADC值会升高,已发现这都是良好的预后预测指标,并且我们未发表的数据也证实了相似的发现[75,76]。

影像引导下经皮穿刺介入治疗

在确诊和制定治疗计划时,可以实施影像引导下经皮穿刺活检。在未手术的患者中,为治愈或者缓解疾病,可以进行影像引导下经皮穿刺治疗,包括冷冻消融术、射频消融术和微波消融术。

经皮穿刺活检

经皮细针穿刺活检是一种微创检查,可以确诊肺部恶性病变。其最常见的并发症是气胸和出血。有报道在对较小和较深病灶进行活检时,气胸的发生率较高。活检小于2cm的病灶气胸的发生率是大于4 cm病灶的11倍,这可能与成功穿刺较小病灶需要更长的时间有关系[77]。这项研究也表明对贴近胸膜的病灶活检时气胸发生的风险是微不足道的,因为针不需要穿过肺,但是对于胸膜上小于2 cm的病灶活检时气胸的发生率增加了7倍,而大于2 cm的病灶则增加了4倍[77]。因此,作者主张使用较长的针斜入进行胸膜下肺结节活检来降低气胸的发生,但是另外一项不同的研究表明较小的进针角度增加了气胸的发生率[78]。对胸膜上小于2cm的病灶进行活检时,可能增加气胸发生的其他因素,包括多处穿刺进针和切割针锚定困难。许多研究报道了对有阻塞性肺疾病的患者进行活检时,气胸的发生率升高[78,79],但是其他研究并没有发现他们之间的相关性[77,80,81]。与气胸发生率升高无关的因素包括空腔病灶活检、活检针粗细及活检时患者摆位等[77]。出血是肺穿刺活检第二大常见的并发症,并且两个主要的诱发因素是病灶大小和胸膜表面距病灶的距离。小于2 cm的病灶相比大于4 cm的病灶出血的发生率增加了6倍,而胸膜上大于2 cm的病灶相比于邻近胸膜表面的病灶出血的发生率,前者是后者的10倍[77,82]。在活检旁边出现的胸腔积液与出血的发生率减低是相关的,并且发现它是活检后出血的一个独立危险因素[77]。

冷冻消融术

冷冻消融术是一种用于治疗不能手术的肺癌患者的微创技术。冷冻消融术引起肿瘤细胞和脉管系统的凝固性坏死。在冷冻消融术中,除去病灶周围正常组织边缘2~3 cm,比较安全。冷冻消融探针头到达肿瘤部位,–40℃处理10min,然后解冻8 min,再冷冻处理10 min。探头周围结冰破坏了细胞膜的功能和酶活性,形成相对高渗的细胞外坏境导致细胞由于渗透作用而脱水。在解冻过程中水快速返回到细胞中导致细胞裂解。小血管壁(<3 cm)的直接损伤,以及供应肿瘤的血流停滞,或许也在肿瘤破坏中发挥着作用[83]。下面是有关于冷冻消融术治疗肺癌的长期效应的数据报道:日本一项20例患者(35个病灶)的研究,随访28个月,结果显示局部复发率为20%[84]。另一项关于Ⅰ期不适合标准手术切除治疗的NSCLC患者的研究显示,经冷冻消融、射频消融(RFA)或者结节切除治疗的3年生存率分别为77%、88%和87%[85]。尽管冷冻消融术在治疗不能手术的肺癌患者时可以与其他消融技术相媲美,但是需要长期的随访数据来证实它在肺癌治疗中发挥的作用。

射频消融术

RFA是一种将电极置入组织中,通过释放热能导致局部破坏的技术。当使用交流电频率在460~500 kHz时,通过周围组织中继发离子逸散的摩擦而产热。组织受热50 ℃至少5 min就会引起细胞发生凝固性坏死。治疗时RFA目标是使组织受热达60 ℃~100 ℃,这使得蛋白变性导致邻近细胞立即发生凋亡[86]。RFA是肺部结节病灶理想的治疗方式,因为病灶周围肺实质中的空气会隔绝热量外散使射频的能量都集中在病灶内。不能手术或者拒绝手术的患者是RFA潜在的治疗对象,但是对于是否接受RFA治疗最好应当经过多科肺部肿瘤会议商讨后决定。最适合使用RFA治疗的是小于3 cm的病灶,Ⅰ期NSCLC患者是RFA的理想治疗对象。据报道,经RFA治疗的Ⅰ期NSCLC患者的1、2、3、4、和5年生存率分别是78%、57%、36%、27%和27%[87]。RFA联合常规放疗已经用于治疗不可切除肺癌的治疗,因为肿瘤中心的乏厌氧细胞对于单纯放疗反应很差。一项研究显示Ⅰ期NSCLC经RFA和常规放疗联合治疗后,2年和5年的累积生存率分别是50%和39%[88],而且相比单纯放疗,双重治疗方案能获得更好的肿瘤局部控制和患者生存[89]。另外,RFA能用于治疗较小的,生长较慢的肺部转移灶[90],并能缓解拥有较大肿瘤患者的症状如胸痛、呼吸困难、咳嗽或咯血等[87]。RFA治疗较大的肿瘤时,常常需要多重消融以保证较满意的肿瘤覆盖范围,而且相比较小肿瘤,较大肿瘤往往拥有更高的复发率[87,89]。

微波消融术

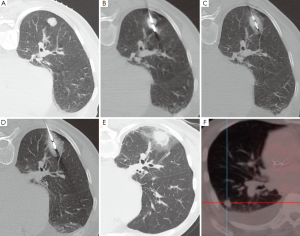

除了日益发展的微创热能消融治疗设备,微波消融(MWA)代表了目前对于不能手术的肺部恶性肿瘤最先进的治疗方法[91]。微波是频率范围从300 MHz到300 GHz的电磁波。然而,临床使用的微波设备频率是从915 MHz到2.45 GHz[92]。在靶组织中,微波激发水分子等小的带电极性的分子,并且为随着快速改变的电场发生着每秒钟20亿~50亿次的旋转[92,93]。这导致摩擦而产生热量。传导和对流使组织温度进一步升高微波消融,超过直接激发水分子产热[94]。因此温度升高,经常会超过100 ℃,几乎导致细胞发生不可逆转的损伤。在球形的微波线周围,形成日益增加的离心样分布的凝固性坏死。理想范围是它包括肿瘤靶区,周围的圆周区域是“安全边缘”(图2)。至少6 mm厚的“安全边缘”,需要破坏不能在横断层面成像上感知的肿瘤癌巢和贴近肿瘤外周的卫星灶。“安全边缘”越小,局部复发率越高[95]。

MWA相比RFA的优势

微波相比于RF能量有多个优势。RF产热需要电传导途径,因此在低导电和高电阻的部位效果较差,例如肺实质。这导致只有在邻近RF电极的靶组织区域热能较高才能达到较高的热能[96,97]。即使在低导电、高电阻或者低热传导的部位[98],微波也能够在多种组织中扩散并有效的升高组织温度。在构建的所有超热消融设备中,微波均能够穿透烧焦或者枯焦的组织,而使非微波能量系统有限的功率输出[99]。当将多个微波线彼此靠近时可同时输出能量以使消融体积达到最大,或者广泛的消融空间,可同时消融多个肿瘤,例如多发性肺转移灶[95]。MWA能够获得更大和更均匀的消融体积,因为MWA快速产热会不易产生热库效应[92]。MWA对于RFA的优势还包括不需要接地垫,这可以避免接地垫部位的潜在灼伤,而且植入心脏的设备也较少发生功能障碍[100,101]。

微波消融病灶的详细组织病理评估已经证实同心层状消融区域像Clasen等描述的RFA治疗后的组织病变[102]。中心部位坏死区为被同样不可逆的毁损的组织所包围,后者与保留的安全边缘相对应。外层的出血环被磨玻璃样外层包围,再外面层是水肿和淋巴细胞浸润[103]。在最外层,只有部分被RFA破坏的发热细胞[102]。在较大的消融区,在术中对做过MWA的肺癌肿块进行组织化学烟碱腺嘌呤二核苷酸染色优于肿块切除后再确定细胞死亡(因为切除后组织细胞缺少线粒体酶活性)[104]。在5/6的消融病灶中不能检测到存活细胞;通过界限清楚区分活细胞和非存活细胞的交界区域,可以观察到均匀一致的细胞死亡。

患者选择和方法

选择做MWA的患者往往是医学上认为不能手术的。MWA的排除标准包括不能控制的原发性肿瘤,有淋巴结转移的影像学证据,胸腔内扩散,胸壁、纵隔、主支气管或者主肺动脉的浸润,败血症以及不可逆转的凝血障碍[94,105]。做过手术(包括肺切除术)、化疗或者放疗的患者往往也被排除。一些患者可能有可切除的肿瘤,一些患者的肿瘤可能可以切除,但是拒绝手术。患者在CT扫描下定位,寻找最短和最安全到达肿瘤的途径。可能的话,裂隙应当避免。常规备皮铺巾,局麻药沿着针束浸润麻醉。MWA的电极通过皮肤的短切口顺利进入。在可见引导下优先选择CT透视,微波线逐步进入肿瘤部位。应当避开钙化灶和软骨组织,因为如果易碎的微波线碰到坚硬组织时就可能有破裂的危险[106]。镇静或者一般的麻醉在两种治疗模式中于并发症发生率和疗效上没有什么区别[107]。单个病灶的消融时间依赖于肿瘤大小、位置和探头的功率,但是一般不会超过20 min。在消融病灶过程中建议进行局部CT扫描以辨别原位或者早期并发症所致的微波线的位置改变。仅有少数机构在此操作前常规预防性使用抗生素[108]。操作后立即给予持续监测脉搏和血氧饱和度,每15~20min监测一次血压。其他检查根据每个医院政策各异。操作3~4小时后进行胸片检查。在大部分操作中心,操作后患者留院,第二天没有任何并发症发生可以出院。 原则上,此过程可以在门诊患者中进行,但是建议观察他们一晚上,因为有可能出现潜在的、较晚出现的并发症。

并发症

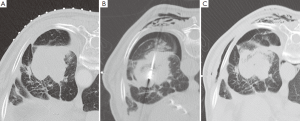

由于操作而出现的并发症应当根据不良事件常用术语标准(CTCAE)进行分类[109]。MWA过程中出现的并发症的发生率是不同的,而且在拥有较差潜在肺储备能力的患者中其发生率可能更高。气胸是最常见的即刻发生的并发症,根据报道其发生率达43%[110],但是其中只有不到1/3的患者需要插管[105,110,111]。消融后综合征,定义为有持续咳嗽(合并或不合并咯血)、治疗区域疼痛,并且消融后几天内这些症状持续存在,据报道其发生在2%的患者中[105]。发生不需要进行胸腔穿刺术的少量胸腔积液的患者在全部消融治疗患者中约占1/4。据报道发生空腔改变的在消融肿瘤病灶中达43%,这其中14%自发出现错综复杂的气液平面[105]。感染并发症(脓肿、肺炎)发生率很低[105,110]。胸壁气肿发生率约为20%(作者经验,未有报道),并且常和气胸同时发生(图3)。消融邻近脏层胸膜的肿瘤导致超过1/3的患者出现胸膜增厚[105],并且一段时间后在少部分患者中出现胸膜收缩。达15%的患者MWA后由于气胸需要留院[105]。

由于最近除了MWA之外其他微创超热治疗设备的出现,很少用数据对比肺癌经MWA的的长期疗效;不同的MWA协议用于不同的消融设备,带有不同的快速冷却设备、消融线大小和探头长度来运行不同的频率;治疗异质性患者人群包括简单治疗过的原发性肺癌、治疗后局部复发的原发性肺癌、同步或者异时出现的肺癌和肺转移病灶。最近两个使用相同的MWA设备和相似操作协议的文章均展示了较好的短中期疗效。在早期NSCLC的同质患者人群中,6个月和1年的局部控制率分别为88%和75%[110,111]。

治疗后评价

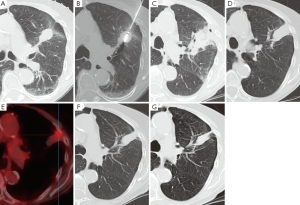

尽管需要接触放射线,CT仍是随访时最常选择的影像学方法。消融后常规的检查手段是消融后一天进行CT检查以评价并发症,而且此次检查能用来作为与随后检查对比的参考,随后将在第一年的3、6、12个月,以后每隔6个月进行检查[110]。消融后6个月能看到病灶周围对称环形边缘(<5 mm)增强,考虑是良性反应性增强的标志。然而,大于15HU的不规则局灶软组织增强被认为是疾病残余或者复发的标志[105]。消融区域最初的范围应当比需要治疗的肿瘤病灶更大,因为它包括周围的安全边缘。以后会出现持续的收缩,这常会产生小的局部肺不张(图4)或者瘢痕。FDG-PET影像检查对于检测早期肿瘤复发更加敏感。然而,在消融后的早期,它的特异性很低。不推荐消融后少于6个月进行FDG-PET扫描检查,以保证较低的假阳性率[112,113]。除了FDG吸收值,FDG的吸收模式也是判断消融成功或者失败的指标[113]。修改后的实体瘤反应评价标准(RECIST)联合消融后检测出病灶的CT和FDG-PET检查,被认为是随访评价最合适的检测工具[114]。

结论

目前影像学所面临的挑战是发掘每一种影像学检查方法的优势,将这些优势集合起来应用于临床中。目前,CT和PET/CT推荐用于肺癌分期中,MR影像检查用于评价可疑的T3和T4疾病。最近一些解剖和功能研究显示MR在NSCLC分期中与FDG-PET/CT等效。CT、PET/CT和MR新的进展为改善肺癌的解剖和功能评价提供了可能,致使更加个体化和靶向治疗的实现。冷冻消融术、RFA和MWA是肺癌治愈或者局部缓解非常有前景的经皮穿刺技术,但是有报道短中期数据表明MWA效果要优于RFA。然而,更多的中长期数据需要评价经过这些治疗后存活率和肿瘤无病生存期。

Acknowledgements

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ravenel JG, Mohammed TL, Movsas B, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® noninvasive clinical staging of bronchogenic carcinoma. J Thorac Imaging 2010;25:W107-11. [PubMed]

- Willemink MJ, Leiner T, de Jong PA, et al. Iterative reconstruction techniques for computed tomography part 2: initial results in dose reduction and image quality. Eur Radiol 2013;23:1632-42. [PubMed]

- Vardhanabhuti V, Loader RJ, Mitchell GR, et al. Image quality assessment of standard- and low-dose chest CT using filtered back projection, adaptive statistical iterative reconstruction, and novel model-based iterative reconstruction algorithms. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2013;200:545-52. [PubMed]

- Walsh SL, Nair A, Hansell DM. Post-processing applications in thoracic computed tomography. Clin Radiol 2013;68:433-48. [PubMed]

- Stoelben E, Ludwig C. Chest wall resection for lung cancer: indications and techniques. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2009;35:450-6. [PubMed]

- Bandi V, Lunn W, Ernst A, et al. Ultrasound vs. CT in detecting chest wall invasion by tumor: a prospective study. Chest 2008;133:881-6. [PubMed]

- Higashino T, Ohno Y, Takenaka D, et al. Thin-section multiplanar reformats from multidetector-row CT data: utility for assessment of regional tumor extent in non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Radiol 2005;56:48-55. [PubMed]

- Silvestri GA, Gonzalez AV, Jantz MA, et al. Methods for staging non-small cell lung cancer: diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2013;143:e211S-50S.

- Volterrani L, Mazzei MA, Banchi B, et al. MSCT multi-criteria: a novel approach in assessment of mediastinal lymph node metastases in non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Radiol 2011;79:459-66. [PubMed]

- Takahashi Y, Takashima S, Hakucho T, et al. Diagnosis of regional node metastases in lung cancer with computer-aided 3D measurement of the volume and CT-attenuation values of lymph nodes. Acad Radiol 2013;20:740-5. [PubMed]

- De Wever W, Vankan Y, Stroobants S, et al. Detection of extrapulmonary lesions with integrated PET/CT in the staging of lung cancer. Eur Respir J 2007;29:995-1002. [PubMed]

- Pfister DG, Johnson DH, Azzoli CG, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology treatment of unresectable non-small-cell lung cancer guideline: update 2003. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:330-53. [PubMed]

- Crinò L, Weder W, van Meerbeeck J, et al. Early stage and locally advanced (non-metastatic) non-small-cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2010;21:v103-15. [PubMed]

- Colt HG, Murgu SD, Korst RJ, et al. Follow-up and surveillance of the patient with lung cancer after curative-intent therapy: diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2013;143:e437S-54S.

- Junker K, Thomas M, Schulmann K, et al. Tumour regression in non-small-cell lung cancer following neoadjuvant therapy. Histological assessment. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 1997;123:469-77. [PubMed]

- Lou F, Huang J, Sima CS, et al. Patterns of recurrence and second primary lung cancer in early-stage lung cancer survivors followed with routine computed tomography surveillance. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2013;145:75-81. [PubMed]

- Revel MP, Merlin A, Peyrard S, et al. Software volumetric evaluation of doubling times for differentiating benign versus malignant pulmonary nodules. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2006;187:135-42. [PubMed]

- Fraioli F, Anzidei M, Zaccagna F, et al. Whole-tumor perfusion CT in patients with advanced lung adenocarcinoma treated with conventional and antiangiogenetic chemotherapy: initial experience. Radiology 2011;259:574-82. [PubMed]

- Tacelli N, Santangelo T, Scherpereel A, et al. Perfusion CT allows prediction of therapy response in non-small cell lung cancer treated with conventional and anti-angiogenic chemotherapy. Eur Radiol 2013;23:2127-36. [PubMed]

- Yi CA, Lee KS, Kim EA, et al. Solitary pulmonary nodules: dynamic enhanced multi-detector row CT study and comparison with vascular endothelial growth factor and microvessel density. Radiology 2004;233:191-9. [PubMed]

- Johnson TR, Krauss B, Sedlmair M, et al. Material differentiation by dual energy CT: initial experience. Eur Radiol 2007;17:1510-7. [PubMed]

- Chae EJ, Song JW, Seo JB, et al. Clinical utility of dual-energy CT in the evaluation of solitary pulmonary nodules: initial experience. Radiology 2008;249:671-81. [PubMed]

- Schmid-Bindert G, Henzler T, Chu TQ, et al. Functional imaging of lung cancer using dual energy CT: how does iodine related attenuation correlate with standardized uptake value of 18FDG-PET-CT? Eur Radiol 2012;22:93-103. [PubMed]

- Gould MK, Maclean CC, Kuschner WG, et al. Accuracy of positron emission tomography for diagnosis of pulmonary nodules and mass lesions: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2001;285:914-24. [PubMed]

- Hellwig D, Ukena D, Paulsen F, et al. Meta-analysis of the efficacy of positron emission tomography with F-18-fluorodeoxyglucose in lung tumors. Basis for discussion of the German Consensus Conference on PET in Oncology 2000. Pneumologie 2001;55:367-77. [PubMed]

- Gould MK, Sanders GD, Barnett PG, et al. Cost-effectiveness of alternative management strategies for patients with solitary pulmonary nodules. Ann Intern Med 2003;138:724-35. [PubMed]

- Hashimoto Y, Tsujikawa T, Kondo C, et al. Accuracy of PET for diagnosis of solid pulmonary lesions with 18F-FDG uptake below the standardized uptake value of 2.5. J Nucl Med 2006;47:426-31. [PubMed]

- Keith CJ, Miles KA, Griffiths MR, et al. Solitary pulmonary nodules: accuracy and cost-effectiveness of sodium iodide FDG-PET using Australian data. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2002;29:1016-23. [PubMed]

- Lejeune C, Al Zahouri K, Woronoff-Lemsi MC, et al. Use of a decision analysis model to assess the medicoeconomic implications of FDG PET imaging in diagnosing a solitary pulmonary nodule. Eur J Health Econ 2005;6:203-14. [PubMed]

- Dwamena BA, Sonnad SS, Angobaldo JO, et al. Metastases from non-small cell lung cancer: mediastinal staging in the 1990s--meta-analytic comparison of PET and CT. Radiology 1999;213:530-6. [PubMed]

- Gould MK, Kuschner WG, Rydzak CE, et al. Test performance of positron emission tomography and computed tomography for mediastinal staging in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2003;139:879-92. [PubMed]

- Shim SS, Lee KS, Kim BT, et al. Non-small cell lung cancer: prospective comparison of integrated FDG PET/CT and CT alone for preoperative staging. Radiology 2005;236:1011-9. [PubMed]

- Yang W, Fu Z, Yu J, et al. Value of PET/CT versus enhanced CT for locoregional lymph nodes in non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2008;61:35-43. [PubMed]

- Al-Sarraf N, Gately K, Lucey J, et al. Lymph node staging by means of positron emission tomography is less accurate in non-small cell lung cancer patients with enlarged lymph nodes: analysis of 1,145 lymph nodes. Lung Cancer 2008;60:62-8. [PubMed]

- Eloubeidi MA, Cerfolio RJ, Chen VK, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration of mediastinal lymph node in patients with suspected lung cancer after positron emission tomography and computed tomography scans. Ann Thorac Surg 2005;79:263-8. [PubMed]

- Herth FJ, Ernst A, Eberhardt R, et al. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration of lymph nodes in the radiologically normal mediastinum. Eur Respir J 2006;28:910-4. [PubMed]

- Pieterman RM, van Putten JW, Meuzelaar JJ, et al. Preoperative staging of non-small-cell lung cancer with positron-emission tomography. N Engl J Med 2000;343:254-61. [PubMed]

- Yun M, Kim W, Alnafisi N, et al. 18F-FDG PET in characterizing adrenal lesions detected on CT or MRI. J Nucl Med 2001;42:1795-9. [PubMed]

- Cheran SK, Herndon JE 2nd, Patz EF Jr. Comparison of whole-body FDG-PET to bone scan for detection of bone metastases in patients with a new diagnosis of lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2004;44:317-25. [PubMed]

- MacManus MP, Hicks RJ, Matthews JP, et al. High rate of detection of unsuspected distant metastases by pet in apparent stage III non-small-cell lung cancer: implications for radical radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2001;50:287-93. [PubMed]

- van Tinteren H, Hoekstra OS, Smit EF, et al. Effectiveness of positron emission tomography in the preoperative assessment of patients with suspected non-small-cell lung cancer: the PLUS multicentre randomised trial. Lancet 2002;359:1388-93. [PubMed]

- Fischer B, Lassen U, Mortensen J, et al. Preoperative staging of lung cancer with combined PET-CT. N Engl J Med 2009;361:32-9. [PubMed]

- Lardinois D, Weder W, Hany TF, et al. Staging of non-small-cell lung cancer with integrated positron-emission tomography and computed tomography. N Engl J Med 2003;348:2500-7. [PubMed]

- Qu X, Huang X, Yan W, et al. A meta-analysis of 18FDG-PET-CT, 18FDG-PET, MRI and bone scintigraphy for diagnosis of bone metastases in patients with lung cancer. Eur J Radiol 2012;81:1007-15. [PubMed]

- Ettinger DS, Akerley W, Bepler G, et al. Non-small cell lung cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2010;8:740-801. [PubMed]

- Dietlein M, Weber K, Gandjour A, et al. Cost-effectiveness of FDG-PET for the management of potentially operable non-small cell lung cancer: priority for a PET-based strategy after nodal-negative CT results. Eur J Nucl Med 2000;27:1598-609. [PubMed]

- Farjah F, Flum DR, Ramsey SD, et al. Multi-modality mediastinal staging for lung cancer among medicare beneficiaries. J Thorac Oncol 2009;4:355-63. [PubMed]

- Schreyögg J, Weller J, Stargardt T, et al. Cost-effectiveness of hybrid PET/CT for staging of non-small cell lung cancer. J Nucl Med 2010;51:1668-75. [PubMed]

- Søgaard R, Fischer BM, Mortensen J, et al. Preoperative staging of lung cancer with PET/CT: cost-effectiveness evaluation alongside a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2011;38:802-9. [PubMed]

- Dunagan D, Chin R Jr, McCain T, et al. Staging by positron emission tomography predicts survival in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Chest 2001;119:333-9. [PubMed]

- MacManus MR, Hicks R, Fisher R, et al. FDG-PET-detected extracranial metastasis in patients with non-small cell lung cancer undergoing staging for surgery or radical radiotherapy—survival correlates with metastatic disease burden. Acta Oncol 2003;42:48-54. [PubMed]

- De Ruysscher D, Nestle U, Jeraj R, et al. PET scans in radiotherapy planning of lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2012;75:141-5. [PubMed]

- Mac Manus MP, Hicks RJ, Ball DL, et al. F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography staging in radical radiotherapy candidates with nonsmall cell lung carcinoma: powerful correlation with survival and high impact on treatment. Cancer 2001;92:886-95. [PubMed]

- Eschmann SM, Friedel G, Paulsen F, et al. FDG PET for staging of advanced non-small cell lung cancer prior to neoadjuvant radio-chemotherapy. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2002;29:804-8. [PubMed]

- Kolodziejczyk M, Kepka L, Dziuk M, et al. Impact of [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose PET-CT staging on treatment planning in radiotherapy incorporating elective nodal irradiation for non-small-cell lung cancer: a prospective study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2011;80:1008-14. [PubMed]

- Deniaud-Alexandre E, Touboul E, Lerouge D, et al. Impact of computed tomography and 18F-deoxyglucose coincidence detection emission tomography image fusion for optimization of conformal radiotherapy in non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2005;63:1432-41. [PubMed]

- Pommier P, Touboul E, Chabaud S, et al. Impact of (18)F-FDG PET on treatment strategy and 3D radiotherapy planning in non-small cell lung cancer: A prospective multicenter study. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2010;195:350-5. [PubMed]

- Mac Manus MP, Everitt S, Bayne M, et al. The use of fused PET/CT images for patient selection and radical radiotherapy target volume definition in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: results of a prospective study with mature survival data. Radiother Oncol 2013;106:292-8. [PubMed]

- Mac Manus MP, Hicks RJ, Matthews JP, et al. Positron emission tomography is superior to computed tomography scanning for response-assessment after radical radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:1285-92. [PubMed]

- Lee P, Bazan JG, Lavori PW, et al. Metabolic tumor volume is an independent prognostic factor in patients treated definitively for non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer 2012;13:52-8. [PubMed]

- Decoster L, Schallier D, Everaert H, et al. Complete metabolic tumour response, assessed by 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18FDG-PET), after induction chemotherapy predicts a favourable outcome in patients with locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Lung Cancer 2008;62:55-61. [PubMed]

- Pöttgen C, Levegrün S, Theegarten D, et al. Value of 18F-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose-positron emission tomography/computed tomography in non-small-cell lung cancer for prediction of pathologic response and times to relapse after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. Clin Cancer Res 2006;12:97-106. [PubMed]

- Eschmann SM, Friedel G, Paulsen F, et al. 18F-FDG PET for assessment of therapy response and preoperative re-evaluation after neoadjuvant radio-chemotherapy in stage III non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2007;34:463-71. [PubMed]

- Biederer J, Hintze C, Fabel M. MRI of pulmonary nodules: technique and diagnostic value. Cancer Imaging 2008;8:125-30. [PubMed]

- National Lung Screening Trial Research Team, Aberle DR, Adams AM, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med 2011;365:395-409. [PubMed]

- Wu NY, Cheng HC, Ko JS, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging for lung cancer detection: experience in a population of more than 10,000 healthy individuals. BMC Cancer 2011;11:242. [PubMed]

- Gümüştaş S, Inan N, Akansel G, et al. Differentiation of malignant and benign lung lesions with diffusion-weighted MR imaging. Radiol Oncol 2012;46:106-13. [PubMed]

- Yi CA, Shin KM, Lee KS, et al. Non-small cell lung cancer staging: efficacy comparison of integrated PET/CT versus 3.0-T whole-body MR imaging. Radiology 2008;248:632-42. [PubMed]

- Ohno Y, Koyama H, Onishi Y, et al. Non-small cell lung cancer: whole-body MR examination for M-stage assessment--utility for whole-body diffusion-weighted imaging compared with integrated FDG PET/CT. Radiology 2008;248:643-54. [PubMed]

- Sommer G, Wiese M, Winter L, et al. Preoperative staging of non-small-cell lung cancer: comparison of whole-body diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/computed tomography. Eur Radiol 2012;22:2859-67. [PubMed]

- Usuda K, Zhao XT, Sagawa M, et al. Diffusion-weighted imaging is superior to positron emission tomography in the detection and nodal assessment of lung cancers. Ann Thorac Surg 2011;91:1689-95. [PubMed]

- Yang RM, Li L, Wei XH, et al. Differentiation of central lung cancer from atelectasis: comparison of diffusion-weighted MRI with PET/CT. PLoS One 2013;8:e60279. [PubMed]

- Ohno Y, Nogami M, Higashino T, et al. Prognostic value of dynamic MR imaging for non-small-cell lung cancer patients after chemoradiotherapy. J Magn Reson Imaging 2005;21:775-83. [PubMed]

- Iwasawa T, Saito K, Ogawa N, et al. Prediction of postoperative pulmonary function using perfusion magnetic resonance imaging of the lung. J Magn Reson Imaging 2002;15:685-92. [PubMed]

- Koh DM, Scurr E, Collins D, et al. Predicting response of colorectal hepatic metastasis: value of pretreatment apparent diffusion coefficients. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2007;188:1001-8. [PubMed]

- Sedlaczek O. Alteration of MR-DWI/ADC before and 24 hours after induction of chemotherapy in patients with NSCLC. Presented at 3rd World Congress of Thoracic Imaging, Seoul, 2013.

- Yeow KM, Su IH, Pan KT, et al. Risk factors of pneumothorax and bleeding: multivariate analysis of 660 CT-guided coaxial cutting needle lung biopsies. Chest 2004;126:748-54. [PubMed]

- Saji H, Nakamura H, Tsuchida T, et al. The incidence and the risk of pneumothorax and chest tube placement after percutaneous CT-guided lung biopsy: the angle of the needle trajectory is a novel predictor. Chest 2002;121:1521-6. [PubMed]

- García-Río F, Pino JM, Casadevall J, et al. Use of spirometry to predict risk of pneumothorax in CT-guided needle biopsy of the lung. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1996;20:20-3. [PubMed]

- Anderson CL, Crespo JC, Lie TH. Risk of pneumothorax not increased by obstructive lung disease in percutaneous needle biopsy. Chest 1994;105:1705-8. [PubMed]

- Moore EH. Technical aspects of needle aspiration lung biopsy: a personal perspective. Radiology 1998;208:303-18. [PubMed]

- Fish GD, Stanley JH, Miller KS, et al. Postbiopsy pneumothorax: estimating the risk by chest radiography and pulmonary function tests. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1988;150:71-4. [PubMed]

- Hoffmann NE, Bischof JC. The cryobiology of cryosurgical injury. Urology 2002;60:40-9. [PubMed]

- Kawamura M, Izumi Y, Tsukada N, et al. Percutaneous cryoablation of small pulmonary malignant tumors under computed tomographic guidance with local anesthesia for nonsurgical candidates. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2006;131:1007-13. [PubMed]

- Zemlyak A, Moore WH, Bilfinger TV. Comparison of survival after sublobar resections and ablative therapies for stage I non-small cell lung cancer. J Am Coll Surg 2010;211:68-72. [PubMed]

- Gazelle GS, Goldberg SN, Solbiati L, et al. Tumor ablation with radio-frequency energy. Radiology 2000;217:633-46. [PubMed]

- Simon CJ, Dupuy DE, DiPetrillo TA, et al. Pulmonary radiofrequency ablation: long-term safety and efficacy in 153 patients. Radiology 2007;243:268-75. [PubMed]

- Dupuy DE, DiPetrillo T, Gandhi S, et al. Radiofrequency ablation followed by conventional radiotherapy for medically inoperable stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Chest 2006;129:738-45. [PubMed]

- Grieco CA, Simon CJ, Mayo-Smith WW, et al. Percutaneous image-guided thermal ablation and radiation therapy: outcomes of combined treatment for 41 patients with inoperable stage I/II non-small-cell lung cancer. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2006;17:1117-24. [PubMed]

- Steinke K, Glenn D, King J, et al. Percutaneous imaging-guided radiofrequency ablation in patients with colorectal pulmonary metastases: 1-year follow-up. Ann Surg Oncol 2004;11:207-12. [PubMed]

- Wasser EJ, Dupuy DE. Microwave ablation in the treatment of primary lung tumors. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2008;29:384-94. [PubMed]

- Simon CJ, Dupuy DE, Mayo-Smith WW. Microwave ablation: principles and applications. Radiographics 2005;25:S69-83. [PubMed]

- Carrafiello G, Laganà D, Mangini M, et al. Microwave tumors ablation: principles, clinical applications and review of preliminary experiences. Int J Surg 2008;6:S65-9. [PubMed]

- Vogl TJ, Naguib NN, Gruber-Rouh T, et al. Microwave ablation therapy: clinical utility in treatment of pulmonary metastases. Radiology 2011;261:643-51. [PubMed]

- Haemmerich D, Lee FT Jr. Multiple applicator approaches for radiofrequency and microwave ablation. Int J Hyperthermia 2005;21:93-106. [PubMed]

- Schramm W, Yang D, Haemmerich D. Contribution of direct heating, thermal conduction and perfusion during radiofrequency and microwave ablation. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2006;1:5013-6. [PubMed]

- Brace CL. Radiofrequency and microwave ablation of the liver, lung, kidney, and bone: what are the differences? Curr Probl Diagn Radiol 2009;38:135-43. [PubMed]

- Lubner MG, Brace CL, Hinshaw JL, et al. Microwave tumor ablation: mechanism of action, clinical results, and devices. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2010;21:S192-203. [PubMed]

- Skinner MG, Iizuka MN, Kolios MC, et al. A theoretical comparison of energy sources--microwave, ultrasound and laser--for interstitial thermal therapy. Phys Med Biol 1998;43:3535-47. [PubMed]

- Steinke K, Gananadha S, King J, et al. Dispersive pad site burns with modern radiofrequency ablation equipment. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2003;13:366-71. [PubMed]

- Skonieczki BD, Wells C, Wasser EJ, et al. Radiofrequency and microwave tumor ablation in patients with implanted cardiac devices: is it safe? Eur J Radiol 2011;79:343-6. [PubMed]

- Clasen S, Krober SM, Kosan B, et al. Pathomorphologic evaluation of pulmonary radiofrequency ablation: proof of cell death is characterized by DNA fragmentation and apoptotic bodies. Cancer 2008;113:3121-9. [PubMed]

- Crocetti L, Bozzi E, Faviana P, et al. Thermal ablation of lung tissue: in vivo experimental comparison of microwave and radiofrequency. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2010;33:818-27. [PubMed]

- Wolf FJ, Aswad B, Ng T, et al. Intraoperative microwave ablation of pulmonary malignancies with tumor permittivity feedback control: ablation and resection study in 10 consecutive patients. Radiology 2012;262:353-60. [PubMed]

- Wolf FJ, Grand DJ, Machan JT, et al. Microwave ablation of lung malignancies: effectiveness, CT findings, and safety in 50 patients. Radiology 2008;247:871-9. [PubMed]

- Danaher LA, Steinke K. Hot tips on hot tips: technical problems with percutaneous insertion of a microwave antenna through rigid tissue. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol 2013;57:57-60. [PubMed]

- Hoffmann RT, Jakobs TF, Lubienski A, et al. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation of pulmonary tumors--is there a difference between treatment under general anaesthesia and under conscious sedation? Eur J Radiol 2006;59:168-74. [PubMed]

- Carrafiello G, Mangini M, Fontana F, et al. Complications of microwave and radiofrequency lung ablation: personal experience and review of the literature. Radiol Med 2012;117:201-13. [PubMed]

- Retrieved May 20, 2013. Available online:

- Little MW, Chung D, Boardman P, et al. Microwave ablation of pulmonary malignancies using a novel high-energy antenna system. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2013;36:460-5. [PubMed]

- Liu H, Steinke K. High-powered percutaneous microwave ablation of stage I medically inoperable non-small cell lung cancer: a preliminary study. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol 2013. [Epub ahead of print].

- Yoo DC, Dupuy DE, Hillman SL, et al. Radiofrequency ablation of medically inoperable stage IA non-small cell lung cancer: are early posttreatment PET findings predictive of treatment outcome? AJR Am J Roentgenol 2011;197:334-40. [PubMed]

- Singnurkar A, Solomon SB, Gönen M, et al. 18F-FDG PET/CT for the prediction and detection of local recurrence after radiofrequency ablation of malignant lung lesions. J Nucl Med 2010;51:1833-40. [PubMed]

- Herrera LJ, Fernando HC, Perry Y, et al. Radiofrequency ablation of pulmonary malignant tumors in nonsurgical candidates. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2003;125:929-37. [PubMed]

(译者:孟茂斌、王欢欢;校对:范昊哲)

(本译文仅供学术交流,实际内容请以英文原文为准。)