Infections causing central airway obstruction: role of bronchoscopy in diagnosis and management

Introduction

Central airway obstructive infections (CAOI) are interesting and problematic illnesses that have unusual clinical, radiological, and morphological presentations. They may be caused by common or rare pathogens. Individual immune status and comorbid conditions may allow similar infectious pathogens to cause disease states, which have a unique clinical presentation; unusual anatomic distributions, morphological appearances, and outcomes. To this date, there is no comprehensive review addressing this clinical entity, and the medical literature mainly consists of case reports and cases series, which prompted us to write this paper on CAOI. In this article, we focus on the central airway infections causing obstruction and warranting bronchoscopic diagnosis and therapeutic intervention. The PubMed and Embase databases were searched from 1990 to 2016 to identify case reports and case series of central airway infections causing obstruction. We excluded cases of bronchitis or tracheitis caused by common viral or bacterial pathogens that are usually treated medically without any invasive intervention. We also excluded cases of endobronchial tuberculosis (EBTB), as this condition is not uncommon and is considered outside the scope of this paper. We also excluded pediatric cases under the age of 18. A total of 337 cases of central airway infections diagnosed with bronchoscopy were reported, of which 237 had individual case reports and 100 were in case series. We herein provided an overview of the microbiologic, pathologic, radiologic, and bronchoscopic characteristics of infections affecting central airways. We focused on the bronchoscopic modalities that were used to treat CAOIs, such as rigid bronchoscopy, balloon bronchoplasty, endobronchial laser therapy, cryotherapy, and airway stenting. Additionally, we reported on the immune status of patients and management outcomes.

Epidemiology

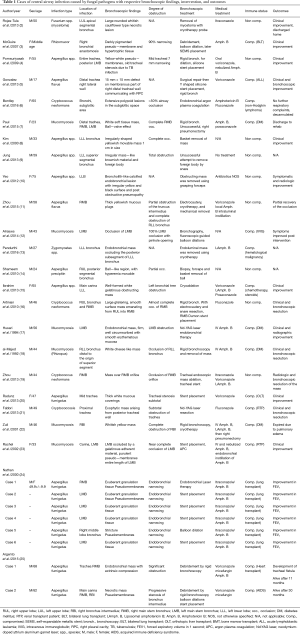

There is no epidemiological data that specifies the prevalence, racial or geographical distribution, and age or gender predominance of CAOI. Case reports and case series from reviews of specific pathogens, which causes CAOIs indicate that the immune status of the host plays a crucial role. In one review by Tasci et al. on aspergillosis causing central airway infections, 16 out of 20 reported patients were on immunosuppressive therapy (1). The prevalence of CAOI is expected to increase as the fields of transplant medicine and oncology evolve and particularly with the rapid growth of interventional pulmonology (IP). Tables 1-3 outline case reports of CAOIs who have undergone bronchoscopic management in the last 26 years. Gender, age, immune status of hosts, the location of specific infection, bronchoscopic view, diagnostic and treatment modalities with outcomes are summarized.

Full table

Full table

Full table

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of CAOI can be challenging. An understanding of a patient’s past medical history, clinical presentation, systemic signs of infection, radiologic and microbiologic evidence of infection, and bronchoscopy based modalities must all be assimilated. Procedural skills may include bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), bronchial washings, protected brush, endobronchial and transbronchial biopsy as well as macroscopic evaluation of lesions. Some cases of CAOI develop at the site of previous disease, anastomosis sites or places where previously inhaled foreign bodies were located. Dicpinigaitis et al. described actinomycosis in a patient with a history of possible chicken bone aspiration. Poor dental hygiene associated with a bony foreign body in the right bronchus intermedius (RBI) caused 90% obstruction (43). In another case, Pornsuriyasak et al. described pseudomembranous tracheobronchitis caused by Aspergillus species (spp.) at the site of previous tracheal stenosis, which had been caused by previous tuberculosis (TB) (4). CAOI can also mimic endobronchial malignancy. In these cases, bronchoscopy with biopsy is indicated for differentiation (44,45).

Clinical presentation

There are no unique clinical symptoms that can distinguish CAOI from other respiratory infections or airway obstruction secondary to other etiology such as malignancy. Dyspnea, cough, fever, and hemoptysis are almost universal presenting signs. Hoarseness and wheezing may indicate large airway involvement with possible obstruction. Suresh et al. reported a case of endobronchial mucormycosis in the left mainstem bronchus (LMB) causing left vocal cord paresis by affecting the left recurrent laryngeal nerve (46). Postobstructive pneumonia is not an uncommon presentation. Rare presentations can be challenging to diagnose, and therefore a high clinical suspicion is required. A cough with expectoration of fungal casts taking the form of the bronchial tree has been observed in fungal obstructing diseases (47). Hemoptysis, although a common presenting symptom of CAOIs, could be a result of broncholiths in the tracheobronchial tree (48), or vascular invasion (47).

In patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), the respiratory symptoms may appear after antiretroviral therapy (ART) as a result of immune reconstitution syndrome. Kim et al. described a case of an endobronchial polypoid mass caused by Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) and occluding the lingular bronchus lumen (49).

Microbiology

CAOIs can be caused by the full spectrum of bacterial, viral, fungal and parasitic pathogens. In contrast to other common respiratory tract infections with highly virulent pathogens causes bronchitis or pneumonia, the host immune status in CAOIs is usually compromised, and even common respiratory tract colonizers or saprophytes can cause serious illness. Microbiological tests differ for each group of pathogens. In all cases, routine blood work, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) status, blood and sputum cultures require examination. Bronchoscopic specimen including biopsy should be sent for histopathological analysis, cytology, histochemical staining and fungal/mycobacterial stains. BAL and bronchial wash for fungal, bacterial, mycobacterial and viral cultures should also be obtained. Specific testing, which may include polymerize chain reaction (PCR) for viral or mycobacterial pathogens, may be needed if the clinical suspicion is high.

Radiology

Chest radiography (CXR) is universal for patients presenting with most respiratory symptoms and is the first step in the radiologic workup. CXR findings are not specific and may be helpful if lobar atelectasis or unilateral lung collapses are seen and indicate main stem bronchial, lobar or segmental bronchi obstruction. Pulmonary infiltrates may be suggestive of major airway involvement depending on suspected pathology. Lee et al. showed that in 121 patients with EBTB, the CXR showed parenchymal infiltration in 58.7% and loss of volume in 34.8% (50). In another study by Qingliang et al., only one out of 22 patients diagnosed with EBTB had a normal chest radiograph (51).

Chest computed tomography (CT) is more informative to localize the abnormality and to assess the severity of obstruction. Chest CT findings of “tree in bud,” focal consolidation with “halo sign,” and many centrilobular small nodules may all be indirect signs of tracheobronchial involvement with infection. The chest CT may show endobronchial or tracheal mass with luminal narrowing, mural thickening, intramural air, and even fistula formation (52). Airway obstruction caused by broncholithiasis or a foreign body with surrounding granulation tissue, due to superimposed infection can be visible on chest CT imaging. Chest CT is more specific for endobronchial actinomycosis as it can show proximal obstructive calcified endobronchial lesions caused by actinomycosis associated with broncholithiasis (43,53,54). Chest CT can be a useful tool prior to bronchoscopic intervention as it can delineate the extent of disease in central airways, give information about the degree of obstruction, and show the presence or absence of fistulae (55).

Pathology

Many patients with CAOI present with the same clinical, radiologic and bronchoscopic findings and tissue sampling is routinely needed to confirm the specific diagnosis. In this paper, we present the CAOI cases by infectious etiology, and we grouped them into fungal, bacterial, viral and parasitic infections. Fungal infections are usually diagnosed using various techniques such as histopathological examination, silver stains, tissue cultures, Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS), or mucus carmin (56-59). Bacterial and viral CAOI are usually diagnosed using real-time PCR, monoclonal antibodies, immunohistochemical staining, gram stain, Ziehl-Neelsen stain and other available tests (40,60).

Bronchoscopy

The role of bronchoscopy is invaluable for the diagnosis of CAOI, however its role in CAOI management and post-treatment surveillance in not well defined. Clinical presentation and imaging are essential for the diagnosis of airway obstruction but bronchoscopy is frequently required to obtain specific diagnosis through direct airway inspection, and tissue sampling using endobronchial biopsy, brush, fine needle aspiration and bronchial washing (51,61). Immunocompromised patients may present with nonspecific respiratory symptoms, and routine bronchoscopy of these patients may help in the diagnosis of endobronchial disease. In the study by Calpe et al., seventy bronchoscopies were performed on 59 HIV patients with respiratory symptoms. Pulmonary TB was diagnosed in 25 patients, six of whom were found to have EBTB (62). Other bronchoscopic techniques such as balloon radial endobronchial ultrasound (R-EBUS) can help to identify the extent of the endobronchial lesions, the invasion depth and the involvement of surrounding structures such as mediastinal vasculature. Using advanced diagnostic bronchoscopy techniques can help the proceduralist in planning the diagnostic as well as the therapeutic procedure and prevent serious complications such as airway perforation or life-threatening bleeding (57,63). In the case described by Handa et al. utilizing bronchoscopy with narrow band imaging (NBI) showed opaque vessels in bronchial subepithelium in the ulcerative lesion. The biopsy of that area revealed Cryptococcus neoformans (64).

Bronchoscopic findings in fungal CAOI

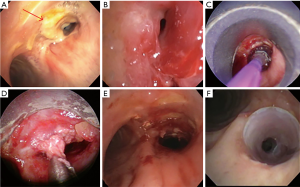

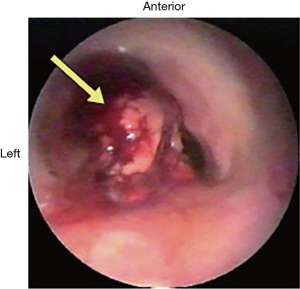

Denning et al. classified airway aspergillosis into four distinct types: pseudomembranous aspergillus tracheobronchitis (ATB), ulcerative ATB, obstructing and invasive ATB (65). The endobronchial appearance of infection can present with by wall edema, pseudomembranes, necrotizing pseudomembranous lesions, ulcerative lesions, whitish or yellowish plaques, endoluminal masses and vegetations (Figure 1) (57,58,66-73). Mucor and Rhizopus are the most commonly reported pathogens of mucormycosis. The endoscopic appearance most commonly seen are mucoid plugs, yellowish or whitish in color, endobronchial mass or polypoid lesions, white cheese like masses, plaques, and areas of necrosis (18,46,59,74-78). In patients with airway cryptococcal infections, the bronchoscopic appearance has been reported as whitish or yellowish masses, mucous plugs, red or white thrush-like plaques, mucosal granularity, white granulation tissue, elevated ulcerated lesions, and polypoid masses (Figure 2) (6,44,64,79-81). Endobronchial histoplasmosis disease is rare but submucosal grayish nodules, ulcers, vesicular lesions as well as masses have been described (82-85). Endobronchial disease with stenosis due to fibrosing mediastinitis has also been reported (86). Coccidioides immitis usually presents as a pulmonary disease, and endobronchial disease is rare. Two mechanisms of endotracheal and endobronchial disease described by Polesky include direct invasion of airways and erosion into the airways from lymph nodes, but the latter is less common (87). Endobronchial involvement can be seen as an obstructing mass, sessile nodular lesions, granular lesions, hyperemic patches and as cobblestoned mucosal involvement (87-89). Other fungal infections such Penicillium marneffei and Fusarium can cause endobronchial disease that may appear as whitish endobronchial masses, large whitish cauliflower necrotic lesion, large polypoid lesions, and granulomatous nodules (2,90-93).

Bronchoscopic findings in bacterial CAOI

Mycobacterium TB is well known to cause endobronchial diseases. The incidence of EBTB has been reported to be from 4.1% to as high as 20% of TB patients (50,94).

In contrast to EBTB, endobronchial disease caused by non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) is rare. Awareness and early diagnosis using bronchoscopic techniques are important.

Most endobronchial NTM infections have been reported to be caused by MAC and Mycobacterium kansasii. In cases of MAC, the bronchoscopic appearance varies and can present as polypoid lesions (34,95-100), endobronchial masses, multiple nodular lesions (101), ulcerative lesions with bronchial strictures (102,103), caseating endobronchial lesions (104) and as white-yellow irregular mucosal lesions. Mycobacterium kansasii has been reported as endobronchial masses, sessile polypoid lesions, mass with ulcerations and nodular lesions (31,105-109). Actinomycosis has been reported in the central airways and can be associated with foreign body and broncholiths. The endobronchial appearance has been described as white and yellow exophytic masses, large broncholith conglomerates and even circumferential ulcerative lesions (43,48,110,111). Other bacterial infections, such as Nocardia can present with endobronchial disease and may present as obstructing tumor-like masses, polypoid lesions, white friable lesions, white ulcerative lesions and necrotic endobronchial masses (112-116).

Klebsiella rhinoscleromatis has also been reported to cause tracheobronchial disease and were previously described as diffuse polypoid lesions, subglottic tracheal tumor—like mass, or mucosal hypertrophy depending on the stage of granulomatous inflammation (36,37,117,118).

Staphylococcus aureus and epidermidis have rarely been reported to cause isolated central airway obstruction (CAO) (119-121). Corynebacterium central airway infection has rarely been reported. Only three cases of major airway infection caused by Corynebacterium spp. were described in the literature. They presented as mild airway erythema, circumferential ulcerations, pseudomembranous plaque-like lesions, and severe obstruction of the trachea (28,29,122).

Bronchoscopic findings in viral CAOI

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) has been reported to cause CAO. Naber et al. reported a case series of three patients with CMV central airway disease. All presented as endobronchial polypoid lesions (40). Imoto et al. reported CMV tracheal disease presenting as an exophytic mass with almost complete obstruction of the distal trachea (123). CMV bronchitis can also be seen as mucosal edema and ulcerations (124). Aventura reported a case of CMV endobronchial infection in a bilateral lung transplant patient presenting as granulation tissue at the site of the left main bronchus stent (39). Herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection localized to the respiratory tract and especially tracheobronchial tree is also not common. Both HSV I and HSV II have been reported to cause central airway disease. It is usually discovered during bronchoscopic examination done for evaluation of respiratory symptoms in immunocompromised patients. In one study by Ben-Izhak, herpetic tracheitis was found in three out of 56 patients who underwent tracheostomy after prolonged intubation (125). Endobronchial findings of central airway disease caused by HSV include fungating and endobronchial masses, polypoid lesions, mucosal irregularities, and ulcerations causing airway stenosis. Necrotic and vesicular blistering lesions have also been identified (60,126-132). The clinical significance of herpetic tracheobronchial disease is unknown as these patients tend to be critically ill with a high overall morbidity and mortality. Similar to HSV, central airway disease caused by varicella zoster virus (VZV) can occur in immunocompromised and in immunocompetent patients and is usually seen with varicella pneumonia. A report of 24 patients with varicella central airway infection by Inokuchi et al. showed a male predominance (19 males and 5 females), and age range of 24 to 60 years. Two patients were immunocompromised and only one patient died (133).

Bronchoscopic findings in parasitic CAOI

Parasitic CAOIs are extremely rare, and there are a few isolated case reports. There is a lack of experience with parasitic CAOIs. Findings are usually incidental during bronchoscopy. Zhang et al. described a case of tracheal leech infection. The patient underwent an evaluation for long-standing dyspnea and hemoptysis. A 5-cm living leech was removed by rigid bronchoscopy. The leech was surrounded by granulation tissue (42). Visceral leishmaniasis with pulmonary involvement and endobronchial disease was described by Kotsifas et al. in immunocompetent patient who presented with a cough and hemoptysis. Bronchoscopy showed mucosal polypoid lesions and biopsy was consistent with leishmania infection (134). A case report of Strongyloides stercoralis causing CAO resulted in death from hemoptysis. Bronchoscopy described yellowish mucosa with multiple nodules with partial obstruction of the airway (135). Lophomonas blattarum is a protozoan that causes infection mainly in immunocompromised hosts (136). Zeng et al. reported a case of Lophomonas blattarum in a patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) who presented with frequent exacerbations without response to treatment. Lophomonas blattarum was diagnosed by bronchoscopy. Macroscopic diffuse swelling, congestion of bronchial mucosa, and purulent secretions were seen (137). These case reports suggest that bronchoscopy may be a useful diagnostic modality for the treatment of resistant respiratory symptoms when parasitic infection is in the differential diagnosis.

Management

Medical management

The treatment of CAOI depends on bronchoscopic findings, laboratory results, and the disease severity. Central airway infections have a propensity to affect the immunocompromised hosts. Broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage is usually required with antibacterial, and sometimes antifungal or antiviral agents. In addition to establishing a specific diagnosis, bronchoscopic interventions may be indicated to relieve airway obstructive symptoms. Treatment of tracheobronchial fungal diseases with long term antifungals (Amphotericin B and its lipid formulations) is most commonly used in critically ill patients (1). Voriconazole, posaconazole, and itraconazole are used when oral therapy is appropriate for long-term treatment. Fluconazole can be used as maintenance therapy for cryptococcal disease and coccidioidomycosis.

CAOI caused by NTM is usually treated with a macrolide, ethambutol, and rifampicin or rifabutin. Some case reports describe quadruple therapy with the addition of amikacin (100,138,139). Actinomycosis usually responds to penicillin therapy. The most commonly used antibiotics for central airway actinomycosis are intravenous (IV) or oral penicillin, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, or amoxicillin (43,48,54,140,141).

The treatment of choice for nocardial disease is trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX), but minocycline and imipenem have also been successful (142). HSV and VZV tracheitis and endobronchial diseases have been conventionally treated with acyclovir and valacyclovir (60,127,128,130). Endobronchial CMV infection is usually treated with ganciclovir (39,123,124).

Surgical management

Surgical treatment has been commonly pursued in patients with mucormycosis, actinomycosis, endobronchial aspergillosis, and nocardial infection. Indications for surgical management include failed medical and bronchoscopic treatment, massive hemoptysis or the concern of massive hemoptysis after bronchoscopic intervention due to the angioinvasive nature of some infections, tracheal obstructions due to mass lesions and inability to ventilate the patient (7,75,110,115,129,143-149). In these latter cases, tracheal resection with removal of the mass and tracheostomy placement was necessary (150).

Timely surgical management may be curative and should be considered in patients with delayed or partial response to medical treatment, or in patients with a high risk of life-threatening hemoptysis.

Bronchoscopic management

Therapeutic bronchoscopy for CAOI is not clearly delineated in the literature, and it is mainly found as scattered case reports and series. The airway management of CAOI is essentially similar to cases of malignant airway obstructions and consist of endobronchial debulking, balloon bronchoplasty, endobronchial laser therapy, argon plasma coagulation, cryotherapy and airway stent placement (151-153). Both flexible and rigid bronchoscopies can be used to treat CAOI. Other techniques such as removing endobronchial lesions using the grasping forceps, baskets and snares have been reported.

In Tables 1-3, we present cases of CAOI that were treated bronchoscopically, and we described the types of infection, locations, bronchoscopic findings and reported outcomes of these patients.

Outcomes

The outcomes of patients who have undergone bronchoscopic intervention to treat CAOIs depend on multiple factors. These include the overall condition of patient, severity of symptoms, immune status, specific infection type and location of infection, degree of airway obstruction, and the response to medical treatment. Whether the type of bronchoscopy procedure affects outcome remains to be determined. Most reported deaths were in the immunocompromised patients with aspergillosis. Favorable outcomes were observed in patients with clinical and radiological improvement on follow-up visits, improvement or resolution of bronchoscopic findings during follow-up repeat bronchoscopies, and improvement of obstruction as measured by spirometry. Tables 1-3 detail reported outcomes in patients who underwent bronchoscopic intervention for CAOI.

Conclusions

Central airway infections causing obstruction are probably rare. Awareness of their existence and the possibility of bronchoscopic intervention for rapid relief of obstructive symptoms or treatment of persistent airway obstruction are important. This article supports the notion that bronchoscopic intervention for CAOI is feasible and similar to interventions for CAO related to other etiologies such as malignant and benign diseases. The literature lacks data about the safety, effectiveness, and outcomes of CAOI treated by bronchoscopic intervention compared to medical therapy alone or with surgical management. Given the unknown epidemiology of CAOI, conducting prospective studies is challenging, and it is currently reasonable to extrapolate data from managing CAO caused by noninfectious etiology to treat patients with CAOI.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Aashish Valvani for assisting in literature search.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Tasci S, Glasmacher A, Lentini S, et al. Pseudomembranous and obstructive Aspergillus tracheobronchitis - optimal diagnostic strategy and outcome. Mycoses 2006;49:37-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rojas-Tula DG, Gomez-Fernandez M, Garcia-Lopez JJ, et al. Endobronchial cryotherapy for a mycetoma. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol 2013;20:330-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McGuire FR, Grinnan DC, Robbins M. Mucormycosis of the bronchial anastomosis: a case of successful medical treatment and historic review. J Heart Lung Transplant 2007;26:857-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pornsuriyasak P, Murgu S, Colt H. Pseudomembranous aspergillus tracheobronchitis superimposed on post-tuberculosis tracheal stenosis. Respirology 2009;14:144-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez M, Ma Tooh M, Krueger T, et al. Repair of tracheal aspergillosis perforation causing tension pneumothorax. Ann Thorac Surg 2013;96:2256-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bentley N, McAfee A, Abbassi AE, et al. An Unusual Cause for Post-Tracheostomy Subglottic Stenosis. Chest 2016;150:184A. [Crossref]

- Paul TK, Oh SS, Bando JM, et al. Central Airway Obstruction From Endobronchial Mucormycosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015;191:A1856.

- Kim JS, Rhee Y, Kang SM, et al. A case of endobronchial aspergilloma. Yonsei Med J 2000;41:422-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jung SW, Kim MW, Cho SK, et al. A Case of Endobronchial Aspergilloma Associated with Foreign Body in Immunocompetent Patient without Underlying Lung Disease. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul) 2013;74:231-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yeo CD, Baeg MK, Kim JW. A case of endobronchial aspergilloma presenting as a broncholith. Am J Med Sci 2012;343:501-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhou XM, Li P, Zhao L, et al. Lung Carcinosarcoma Masked by Tracheobronchial Aspergillosis. Intern Med 2015;54:1905-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alraiyes AH, Almeida F, Cicenia J, et al. Tunneling Through A Mucor Infection! Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014;189:A5710.

- Pendurthi MK, Kao C, Sarkar P, et al. Endobronchial Zygomycosis: A Rare Presentation of a Fatal Infection. Chest 2016;150:136A. [Crossref]

- Shameem M, Bhargava R, Ahmad Z, et al. Endobronchial aspergilloma – Presenting as solitary pulmonary nodule. Respiratory Medicine CME 2010;3:111-2. [Crossref]

- Ibrahim O, Majid A, Paul M, et al. Respiratory Failure Secondary To Obstructive Aspergillus Tracheobronchitis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013;187:A1303.

- Artinian V, Dadayan S, Rahulan V, et al. Endobronchial cryptococcosis: a rare cause of lung collapse. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol 2010;17:76-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Husari AW, Jensen WA, Kirsch CM, et al. Pulmonary mucormycosis presenting as an endobronchial lesion. Chest 1994;106:1889-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- al-Majed S, al-Kassimi F, Ashour M, et al. Removal of endobronchial mucormycosis lesion through a rigid bronchoscope. Thorax 1992;47:203-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhou Q, Hu B, Shao C, et al. A case report of pulmonary cryptococcosis presenting as endobronchial obstruction. J Thorac Dis 2013;5:E170-3. [PubMed]

- Radunz S, Kirchner C, Treckmann J, et al. Aspergillus tracheobronchitis causing subtotal tracheal stenosis in a liver transplant recipient. Case Rep Transplant 2013;2013:928289. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fabbri A, Grazzini M, Vannucci F, et al. Cryptococcosis: an unusual cause of tracheal obstruction. Intern Med 2013;52:1279. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zuil M, Villegas F, Jareño J, et al. Cryotherapy in the diagnosis of endobronchial mucormycosis. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol 2001;8:107-9.

- Rachel H, Francisco A, Ashish S, et al. Treatment of endobronchial mucormycosis with amphotericin B via flexible bronchoscopy. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol 2002;9:294-7.

- Nathan SD, Shorr AF, Schmidt ME, et al. Aspergillus and endobronchial abnormalities in lung transplant recipients. Chest 2000;118:403-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Argento AC, Wolfe CR, Wahidi MM, et al. Bronchomediastinal fistula caused by endobronchial aspergilloma. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2015;12:91-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Folliet L, Perpoint T, Pignat JC, et al. Tumor-bronchial actinomycosis simulating a recurrence of lung cancer 14 years after initial treatment: A case report. Rev Mal Respir 2015;32:524-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kebbe J, Alraiyes AH, Dhillon SS, et al. Lung Abscess Causing Airway Obstruction Requiring Temporary Tracheobronchial Stenting. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol 2016;23:e26-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guerrero J, Mallur P, Folch E, et al. Necrotizing Tracheitis Secondary to Corynebacterium Species Presenting With Central Airway Obstruction. Respiratory care 2014;59:e5-e8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Colt HG, Morris JF, Marston BJ, et al. Necrotizing tracheitis caused by Corynebacterium pseudodiphtheriticum: unique case and review. Rev Infect Dis 1991;13:73-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Patel K, Bhugra P, Dudney T, et al. A 39-year-old man with fevers, cough, and right upper lobe cavitory lesion in lung. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol 2010;17:258-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Manali ED, Tomford WJ, Liao DW, et al. Mycobacterium kansasii endobronchial ulcer in a nonimmunocompromised patient. Respiration 2005;72:305-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Henderson MH, Spradley CD, DeKeratry DR. Pseudomembranous tracheobronchitis due to streptococcus pyogenes: a case report. Chest 2009;136:7S-e-8S. [Crossref]

- Gorbett D, Rivas-Perez H, Bhatt N. An Endobronchial Mass Due to a Mycobacterium avium Complex Infection. Chest 2013;144:184A. [Crossref]

- Shih JY, Wang HC, Chiang IP, et al. Endobronchial lesions in a non-AIDS patient with disseminated Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare infection. Eur Respir J 1997;10:497-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ling IT, Mulrennan SA, Phillips MJ. Multiple endobronchial polyps. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol 2011;18:154-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Verma G, Kanawaty D, Hyland R. Rhinoscleroma causing upper airway obstruction. Canadian respiratory journal 2005;12:43-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bigi A, Bartolomeo M, Costes V, et al. Tracheal rhinoscleroma. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis 2016;133:51-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Buls A, Lejnieks PJ, Ronis I. Two cases of benign tracheal stenosis successfully treated by minimally invasive endobronchial intervention. Eur Respir J 2011;38:3708.

- Aventura E, Rampolla R. Cytomegalovirus Infection Presenting as Bronchial Mass After Bilateral Lung Transplantation. Chest 2011;140:127A. [Crossref]

- Naber JM, Palmer SM, Howell DN. Cytomegalovirus infection presenting as bronchial polyps in lung transplant recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant 2005;24:2109-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chaaban S, Stagner L, Ray C, et al. Viral Infection as a Cause for Bronchostenosis? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015.A5643.

- Zhang P, Zhang R, Zou J, et al. A rare case report of tracheal leech infestation in a 40-year-old woman. Int J Clin Exp Med 2014;7:3599-601. [PubMed]

- Dicpinigaitis PV, Bleiweiss IJ, Krellenstein DJ, et al. Primary endobronchial actinomycosis in association with foreign body aspiration. Chest 1992;101:283-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Balkman JD, Gilkeson RC. Extensive cryptococcal tracheitis mimicking lymphoma in an AIDS patient. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol 2009;16:301-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim YS, Suh JH, Kwak SM, et al. Foreign body-induced actinomycosis mimicking bronchogenic carcinoma. Korean J Intern Med 2002;17:207-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Suresh V, Bhansali A, Sridhar C, et al. Pulmonary mucormycosis presenting with recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy. J Assoc Physicians India 2003;51:912-3. [PubMed]

- Karnak D, Avery RK, Gildea TR, et al. Endobronchial fungal disease: an under-recognized entity. Respiration 2007;74:88-104. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Henry NR, Hinze JD. Broncholithiasis secondary to pulmonary actinomycosis. Respir Care 2014;59:e27-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim HC, Bae IG, Ma JE, et al. Mycobacterium avium complex infection presenting as an endobronchial mass in a patient with acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Korean J Intern Med 2007;22:215-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee JH, Park SS, Lee DH, et al. Endobronchial tuberculosis. Clinical and bronchoscopic features in 121 cases. Chest 1992;102:990-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Qingliang X, Jianxin W. Investigation of endobronchial tuberculosis diagnoses in 22 cases. Eur J Med Res 2010;15:309-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim KH, Choi YW, Jeon SC, et al. Mucormycosis of the central airways: CT findings in three patients. J Thorac Imaging 1999;14:210-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Han JY, Lee KN, Lee JK, et al. An overview of thoracic actinomycosis: CT features. Insights Imaging 2013;4:245-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kassab K, Karnib M, Bou-Khalil PK, et al. Pulmonary actinomycosis presenting as post-obstructive pneumonia. Int J Infect Dis 2016;48:29-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim M, Kang ES, Park JY, et al. Fistula Formation between Right Upper Bronchus and Bronchus Intermedius Caused by Endobronchial Tuberculosis: A Case Report. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul) 2015;78:286-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim DS, Jeong JS, Kim SR, et al. A Case Report of Mass-Forming Aspergillus Tracheobronchitis Successfully Treated with Voriconazole. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e1434. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Casal RF, Adachi R, Jimenez CA, et al. Diagnosis of invasive aspergillus tracheobronchitis facilitated by endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2009;3:9290. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dal Conte I, Riva G, Obert R, et al. Tracheobronchial aspergillosis in a patient with AIDS treated with aerosolized amphotericin B combined with itraconazole. Mycoses 1996;39:371-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Luo LC, Cheng DY, Zhu H, et al. Inflammatory pseudotumoural endotracheal mucormycosis with cartilage damage. Eur Respir Rev 2009;18:186-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Katsenos S, Sampaziotis D, Archondakis S. Tracheal pseudo-tumor caused by herpes simplex virus. Multidiscip Respir Med 2013;8:42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aliyali M, Hedayati MT, Habibi MR, et al. Clinical risk factors and bronchoscopic features of invasive aspergillosis in intensive care unit patients. J Prev Med Hyg 2013;54:80-2. [PubMed]

- Calpe JL, Chiner E, Larramendi CH. Endobronchial tuberculosis in HIV-infected patients. AIDS 1995;9:1159-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Di Carlo P, Cabibi D, La Rocca AM, et al. Post-bronchoscopy fatal endobronchial hemorrhage in a woman with bronchopulmonary mucormycosis: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2010;4:398. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Handa H, Kurimoto N, Mineshita M, et al. Role of narrowband imaging in assessing endobronchial cryptococcosis. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol 2013;20:249-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Denning DW. Invasive aspergillosis. Clin Infect Dis 1998;26:781-803. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Routsi C, Kaltsas P, Bessis E, et al. Airway obstruction and acute respiratory failure due to Aspergillus tracheobronchitis. Crit Care Med 2004;32:580-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cho BH, Oh Y, Kang ES, et al. Aspergillus tracheobronchitis in a mild immunocompromised host. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul) 2014;77:223-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Routsi C, Platsouka E, Prekates A, et al. Aspergillus bronchitis causing atelectasis and acute respiratory failure in an immunocompromised patient. Infection 2001;29:243-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oh HJ, Kim HR, Hwang KE, et al. Case of pseudomembranous necrotizing tracheobronchial aspergillosis in an immunocompetent host. Korean J Intern Med 2006;21:279-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lévy V, Burgel PR, Rabbat A, et al. Respiratory distress due to tracheal aspergillosis in a severely immunocompromised patient. Acta Haematol 1998;100:85-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sada M, Saraya T, Tanaka Y, et al. Invasive tracheobronchial aspergillosis in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus-dermatomyositis overlap syndrome. Intern Med 2013;52:2149-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ağca M, Arinc S, Yilmaz A, et al. A case of endobronchial aspergilloma. Mikrobiyol Bul 2008;42:157-61. [PubMed]

- Angelotti T, Krishna G, Scott J, et al. Nodular invasive tracheobronchitis due to Aspergillus in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 2002;11:325-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gupta V, Rajagopalan N, Patil M, et al. Aspergillus and mucormycosis presenting with normal chest X-ray in an immunocompromised host. BMJ Case Rep 2014.2014. [PubMed]

- Ramìrez T, Alvarez-Sala R, Prados C, et al. Bilobectomy and amphotericin B in a case of endobronchial mucormycosis. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2000;48:245-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mattioni J, Portnoy JE, Moore JE, et al. Laryngotracheal mucormycosis: Report of a case. Ear Nose Throat J 2016;95:29-39. [PubMed]

- Mahajan R, Paul G, Chopra P, et al. Mucormycosis masquerading as an endobronchial tumor. Lung India 2014;31:308-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ferrell BA, Tolle JJ. Invasive endobronchial mucormycosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014;190:e28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chechani V, Kamholz SL. Pulmonary manifestations of disseminated cryptococcosis in patients with AIDS. Chest 1990;98:1060-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mayumi O, Masanori N, Hirotsugu K, et al. Primary Bronchopulmonary Cryptococcosis. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol 2005;12:151-2.

- Chang YS, Chou KC, Wang PC, Yang HB, Chen CH. Primary pulmonary cryptococcosis presenting as endobronchial tumor with left upper lobe collapse. J Chin Med Assoc 2005;68:33-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bhojwani N, Hartman JB, Taylor DC, et al. Nondisseminated histoplasmosis of the trachea. Clin Respir J 2016;10:255-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chanthitivech N, Sirichana W, Jutivorakool K, editors. Rare Cause of Tracheal Ulcer in Post Heart-Lung Transplantation Case. Respirology. NJ USA. 2016.

- Youness H, Michel RG, Pitha JV, et al. Tracheal and endobronchial involvement in disseminated histoplasmosis: a case report. Chest 2009;136:1650-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ross P Jr, Magro CM, King MA. Endobronchial histoplasmosis: a masquerade of primary endobronchial neoplasia--a clinical study of four cases. Ann Thorac Surg 2004;78:277-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Davis AM, Pierson RN, Loyd JE. Mediastinal fibrosis. Semin Respir Infect 2001;16:119-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Polesky A, Kirsch CM, Snyder LS, et al. Airway coccidioidomycosis--report of cases and review. Clin Infect Dis 1999;28:1273-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pendurthi MK, Sarkar P, Guntupalli K. All That Is Miliary Is Not TB: A Case of Disseminated Pulmonary Coccidioidomycosis. Chest 2016;150:127A. [Crossref]

- Chung J, Acosta D, Chen W, et al. Airway Manifestation of Coccidioidomycosis in an Immunocompromised Host. Chest 2012;142:875A. [Crossref]

- Joosten SA, Hannan L, Heroit G, et al. Penicillium marneffei presenting as an obstructing endobronchial lesion in an immunocompetent host. Eur Respir J 2012;39:1540-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boonsarngsuk V, Eksombatchai D, Kanoksil W, et al. Airway obstruction caused by penicilliosis: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Bronconeumol 2015;51:e25-8. [PubMed]

- Zhiyong Z, Mei K, Yanbin L. Disseminated Penicillium marneffei infection with fungemia and endobronchial disease in an AIDS patient in China. Med Princ Pract 2006;15:235-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Terasaki JM, Shah SK, Schnadig VJ, et al. Airway complication contributing to disseminated fusariosis after lung transplantation. Transpl Infect Dis 2014;16:621-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal A, Gupta D, Joshi K, et al. Endobronchial Involvement in Tuberculosis: A Report of 24 Cases Diagnosed by Flexible Bronchoscopy. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol 1999;6:247-50.

- Lisgaris MV, Johnson JL. Worsening pneumonia caused by endobronchial obstruction with Mycobacterium avium complex as a paradoxical response to highly active antiretroviral therapy in AIDS. Infect Dis Clin Pract 2001;10:189-92. [Crossref]

- Gulati A, Singh S, Moussa R, et al. Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare presenting as an endobronchial tumour due to immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. Int J STD AIDS 2012;23:441-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Circo S, Dillard T, Davis W. Endobronchial Mass Due to MAC Infection Despite Macrolide Prophylaxis. Chest 2013;144:32A. [Crossref]

- Fukuoka K, Nakano Y, Nakajima A, et al. Endobronchial lesions involved in Mycobacterium avium infection. Respir Med 2003;97:1261-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Saito W, Kobayashi H, Motoyoshi K, et al. A case of cervical and mediastinal lymphadenopathy with endobronchial nodules in an immunocompetent adult caused by Mycobacterium avium. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol 2002;9:204-8.

- De Gier MG, Mudrikova T, Ekkelenkamp MD, et al. Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome Due To AIDS Related Mycobacterium Avium Infection Mimicking Stadium IV Lung Cancer. D46. CASE REPORTS: FASCINOMAS. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014;189:A6069.

- Asano T, Itoh G, Itoh M. Disseminated Mycobacterium intracellulare infection in an HIV-negative, nonimmunosuppressed patient with multiple endobronchial polyps. Respiration 2002;69:175-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim HI, Kim JW, Kim JY, et al. Isolated Endobronchial Mycobacterium avium Disease Associated with Lobar Atelectasis in an Immunocompetent Young Adult: A Case Report and Literature Review. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul) 2015;78:412-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Iwashima D, Suganuma H, Kobayashi J. A case of endobronchial lesion due to infection with Mycobacterium intracellulare. Kekkaku 2006;81:519-23. [PubMed]

- Park JS, Jung ES, Choi W, et al. Mycobacterium intracellulare Pulmonary Disease with Endobronchial Caseation in a Patient Treated with Methotrexate. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul) 2013;75:28-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Amin RP, Roe DW. An Unusual Presentation Of Mycobacterium Kansasii: The Endobronchial Mass. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;185:A6111.

- Quieffin J, Poubeau P, Laaban J-P, et al. Mycobacterium kansasii infection presenting as an endobronchial tumor in a patient with the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Tuber Lung Dis 1994;75:313-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim MS, Han JW, Jin SS, et al. A Case of Mycobacterium kansasii Pulmonary Disease Presenting as Endobronchial Lesions in HIV-Infected Patient. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul) 2013;75:157-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- LaRocco A Jr, Lucado CS, McGinley MJ. Endobronchial Mycobacterium kansasii during highly active antiretroviral therapy-associated immune reconstitution. Infect Dis Clin Pract 2006;14:62-4. [Crossref]

- Castro JA, Tomashefski JF, Williams SD. Paradoxical worsening of an unusual endobronchial lesion. Chest 2009;136:60S-d-61S. [Crossref]

- Hagan ME, Klotz SA, Bartholomew W, et al. Actinomycosis of the trachea with acute tracheal obstruction. Clin Infect Dis 1996;22:1126-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Takhalov Y, Kileci J, Abdelhadi S. A. Mirage: Endobronchial Actinomycosis Mimicking Carcinoid Tumor. Chest 2016;150:774A. [Crossref]

- Fielding DI, Oliver W. Endobronchial nocardial infection. Thorax 1994;49:385. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kumar N, Ayinla N. Endobronchial pulmonary nocardiosis. Mt Sinai J Med 2006;73:617-9. [PubMed]

- Ohya M, Nakamura Y, Yoshida M, et al. A case of nocardiosis with associated endobronchial excavated lesions. Kansenshogaku Zasshi 2012;86:592-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Akagawa S, Hebisawa A, Shishido H, et al. Mycetoma-forming pulmonary nocardiosis and endobronchial polypoid lesion. Nihon Kyobu Shikkan Gakkai zasshi 1997;35:878-82. [PubMed]

- Guthrie R, Rudinsky D. Pulmonary Nocardiosis Presenting as Endobronchial Mass in an Immunocompetent Host. Chest 2016;150:182A. [Crossref]

- Yigla M, Ben-Izhak O, Oren I, et al. Laryngotracheobronchial involvement in a patient with nonendemic rhinoscleroma. Chest 2000;117:1795-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Soni NK. Scleroma of the lower respiratory tract: a bronchoscopic study. J Laryngol Otol 1994;108:484-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Osakabe Y, Tazawa S, Kanesaka S, et al. Four cases of airway infections caused by MRSA (methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus). Nihon Kyobu Shikkan Gakkai Zasshi 1990;28:368-73. [PubMed]

- Reagle Z, Patel J, Evans T, editors. Community-Acquired Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Causing Necrotizing Tracheobronchitis. Philadelphia: Journal of Investigative Medicine, 2011.

- Kadowaki T, Hamada H, Fujiwara A, et al. Bacterial tracheobronchitis. A rare cause of adult airway stenosis. Respirology 2009;14:1214-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guy B, O'Loghlen S, Petriw L, et al. A Case of Corynebacterium Striatum Disseminated Infection and Pneumonia in a Patient With Relapsed Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Chest 2016;150:197A. [Crossref]

- Imoto EM, Stein RM, Shellito JE, et al. Central airway obstruction due to cytomegalovirus-induced necrotizing tracheitis in a patient with AIDS. Am Rev Respir Dis 1990;142:884-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hozumi H, Fujisawa T, Kuroishi S, et al. Ulcerating Bronchitis Caused by Cytomegalovirus in a Patient with Polymyositis. Intern Med 2012;51:2933-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ben-Izhak O, Ben-Arieh Y. Necrotizing squamous metaplasia in herpetic tracheitis following prolonged intubation: a lesion similar to necrotizing sialometaplasia. Histopathology 1993;22:265-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Upadya A, Tilluckdharry L, Nagy C, et al. Endobronchial pseudo-tumour caused by herpes simplex. Eur Respir J 2005;25:1117-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thong L, Plant BJ, McCarthy J, et al. Herpetic tracheitis in association with rituximab therapy. Respirol Case Rep 2016;4:e00158. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Armbruster C, Drlicek M. Herpes simplex virus type II infection as an exophytic endobronchial tumor. Wien Klin Wochenschr 1995;107:344-6. [PubMed]

- Wu CH, Lin WC. HSV pneumonia and endobronchial clusters of vesicles. QJM 2015;108:163-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hammar M, Silverman J, Krishnamurti U, et al. Postobstructive Pneumonia with an Interesting Twist. Chest 2014;145:469A. [Crossref]

- St John RC, Pacht ER. Tracheal stenosis and failure to wean from mechanical ventilation due to herpetic tracheitis. Chest 1990;98:1520-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Villar A, García-Tejedor JL, Leiro Fernández V, et al. Tracheobronchial wall thickening secondary to herpesvirus infection in a patient with Good's syndrome. An Med Interna (Madrid) 2008;25:234-6. [PubMed]

- Inokuchi R, Nakamura K, Sato H, et al. Bronchial ulceration as a prognostic indicator for varicella pneumonia: Case report and systematic literature review. J Clin Virol 2013;56:360-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kotsifas K, Metaxas E, Koutsouvelis I, et al. Visceral leishmaniasis with endobronchial involvement in an immunocompetent adult. Case Rep Med 2011;2011:561985. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ochoa MD, Ramírez-Mendoza P, Ochoa G, et al. Nódulos bronquiales producidos por Strongyloides stercoralis como causa de obstrucción bronquial. Arch Bronconeumol 2003;39:524-6. [PubMed]

- Wang Y, Tang Z, Ji S, et al. Pulmonary Lophomonas blattarum infection in patients with kidney allograft transplantation. Transpl Int 2006;19:1006-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zeng H, Kong X, Chen X, et al. Lophomonas blattarum infection presented as acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:E73-E76. [PubMed]

- Kang SH, Mun SK, Lee MJ, et al. Endobronchial Mycobacterium avium Infection in an Immunocompetent Patient. Infect Chemother 2013;45:99-104. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rad AM, Toth JW, Reed MF, et al. Endoluminal Mass In A Patient With Silicosis: A Rare Presentation Of Mycobacterium Avium Complex And Actinomyces. A3. FELLOWS CASE CONFERENCE. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015;191:A6485.

- Ho JC, Ooi GC, Lam WK, et al. Endobronchial actinomycosis associated with a foreign body. Respirology 2000;5:293-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dalhoff K, Wallner S, Finck C, et al. Endobronchial actinomycosis. Eur Respir J 1994;7:1189-91. [PubMed]

- Singh I, West FM, Sanders A, et al. Pulmonary Nocardiosis in the Immunocompetent Host: Case Series. Case Rep Pulmonol 2015;2015:314831. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fermanis GG, Matar K, Steele R. Endobronchial zygomycosis. Aust N Z J Surg 1991;61:391-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ling Hsu AA, Pena Takano AM, Wai Chan AK. Beyond removal of endobronchial foreign body. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014;189:996-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tam WO, Wong CF, Wong PC. Endobronchial nocardiosis associated with broncholithiasis. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis 2008;69:183-5. [PubMed]

- Warman M, Lahav J, Feldberg E, et al. Invasive tracheal aspergillosis treated successfully with voriconazole: clinical report and review of the literature. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2007;116:713-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pacheco P, Ventura A, Branco T, et al. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis and zygomycosis in an Aids patient. Clinical Microbiology & Infection 2012;18:821.

- Klada E, Thomas R, Bansal R, et al. Pulmonary Mucormycosis With Endobronchial Lesion Presented as Recurrent Hemoptysis for Five Years. Chest 2012;142:169A. [Crossref]

- Maddox L, Long GD, Vredenburgh JJ, et al. Rhizopus presenting as an endobronchial obstruction following bone marrow transplant. Bone Marrow Transplant 2001;28:634-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wolf O, Gil Z, Leider-Trejo L, et al. Tracheal mucormycosis presented as an intraluminal soft tissue mass. Head Neck 2004;26:541-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shah P. Atlas of Flexible Bronchoscopy. CRC Press, 2011.

- Ernst A, Feller-Kopman D, Becker HD, et al. Central airway obstruction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004;169:1278-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guibert N, Mhanna L, Droneau S, et al. Techniques of endoscopic airway tumor treatment. J Thorac Dis 2016;8:3343. [Crossref] [PubMed]