低剂量CT筛查肺癌的应用进展

前言

2008年大约140万人死于肺癌[1],肺癌是全世界癌症患者的主要死因。肺癌发病率及病死率的升高紧随吸烟流行趋势,并具有20年的时间延后,这可以解释诸如美国等国家肺癌的病死率下降或处于稳定水平,而中国肺癌病死率在上升的现象[2,3]。肺癌预后较差,欧美报道的5年生存率为8%~16%,中国报道的5年生存率为6%~32%[4-6]。

当前25%~30%的患者表现为局限性、潜在可治愈的疾病,这些IA期的非小细胞肺癌(NSCLS)患者的5年生存率为73%,相反那些远处转移的患者预后很差(5年生存率13%)[7,8]。

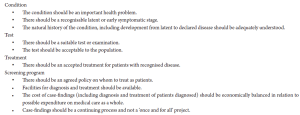

鉴于肺癌有可检测的临床前阶段、有效的治疗(特别是手术)、潜在有效适用的具有成本效益的筛查方法,看起来符合Wilson和Jungner所描述的可进行筛查实验的标准[9](框1)。尽管应用胸部平片(CXR)进行筛查有很多方法学上的缺点[11],而且通过PLCO癌症筛查试验结果来看CXR也并没有带来生存获益[12],但这种方法依然是被普遍接受的。相比之下,CT是一种更加敏感的显像模式,过去25年CT一直被研究用于肺癌的筛查。最近国家肺癌筛检试验(NLST)[13]研究结果显示与CXR相比,低剂量CT(LDCT)筛查降低了20%的肺癌病死率。这项研究首次通过随机对照试验证实,通过筛查可降低病死率。几个专家团体基于这些新的发现在美国发布了筛查肺癌高危人群的指南,美国预防服务工作组把其判定为B级推荐方案[14-17]。

Full table

LDCT筛查——实际问题和技术因素

实施LDCT筛查高危人群时,面对的最重要的问题是:较高频率的阳性检测结果,主要是肺结节。

结节检测

肺结节可以较好或者较差地定义为圆形或不规则的不透明体,测量直径达3 cm[18]。但识别结节具有内在的主观性,在不同的阅片者之间或者同一个阅片者多次阅片时,存在变异性,即使是在具有丰富经验的放射学家之间,也存在这种变异性[19,20]。

相当大比例的结节初次阅片时可能被忽略,需要在接下来的回顾性阅片时才能被确定[21]。结节检出率可能因“第二个阅片者”的参与而增加[22],比如图像格式化、最大强度投影(MIPs)[23-25]或计算机辅助诊断(CAD)系统软件均可作为“第二阅片者”[26-28]。

结节评估

以下四个重要方面可对结节进行很好的分类:尺寸、衰减、是否存在钙化、当可获得连续随访的图像时可计算时间间隔增长率。

尺寸

结节尺寸是非常重要的恶性肿瘤预测因子(图1)[29-31]。通过对基线NLST试验结果分析发现:恶性肿瘤结节直径为7~10 mm时阳性预测值(PPV)为1.7%,当结节直径增大为:11~20 mm、21~30 mm、>30 mm时,阳性预测值分别增加为11.9%、29.7%和41.3%[32]。然而即使是非常小的结节(微结节),也有一些恶性肿瘤的风险,比如230个<5 mm直径结节中有3个结节(1.3%)在基线扫描随访1年后确诊为恶性[33]。

衰减

某些结节中的钙化模式和内部结节性脂肪,可确切地提示其为良性[34],然而许多结节太小而不能分辨其内部特性,这一类结节被简单地归类为“非钙化的结节”(NCNs)。NCNs很常见,见于25%~50%的LDCT扫描中。

大多数的NCNs是“实性的”(软组织)放射衰减。其余分为非实性结节(NSNs),并进一步细分为纯毛玻璃结节(pGGO)或混合(部分固体)衰减结节(实性的和毛玻璃混合;psGGO)。同一性质结节在不同研究间具有差异(图2)。GGOs的意义将在下面进行讨论。

毛玻璃结节

ELCAP研究报道基线扫描结节的阳性率为233/1 000。19%的病变为pGGO或psGGO(患病率4.4%;层厚10 mm),共检测到27例癌症患者。在对尺寸这个因素进行校正之后发现,psGGO恶性率为63%,实性结节的恶性率为32%,pGGOs的恶性率为13%[35]。其他的研究特别强调新发的或逐渐增多的实性NSNs的重要性,如果发现此类NSNs则高度怀疑肺癌[36-38]。最近的研究表明,许多NSNs会自发地分解。Felix [39]报道了37/280例患者,其中有75个GGOs(患病率13%;层厚0.75 mm)。筛查研究的人口是非典型的,因为超过一半的人有肺癌或头部癌症病史。大约一半的GGOs在基线筛查时被检测到,但在平均29个月随访之后消失。没有形态学特征可明确鉴别分解或者未分解的GGOs。Kwon[40]报道了通过筛选186例患者,检测到69个pGGO和117个psGGO(总筛查数没有报告,层厚5 mm)。3个月后45%的患者结节退化或消失,恶性和良性病灶大小相似(平均15~16 mm),只有27%(33/122)是恶性的,但这也许只反映了短随访的结果(平均随访时间8.6个月,文章发表前64个病例仍在积极随访)。第二项由韩国人进行的研究显示[41],在93/16 777(0.5%)非典型筛查结果中确认了126个直径>5 mm的NSNs,其中的44个患者从未吸烟,70%的NSNs是短暂出现的,年纪较轻、在随访扫描中发现、血嗜酸性粒细胞、多个病灶、较大的固体成分、模糊的边界是判断NSNs是否短暂出现的独立预测因子。马里奥从一个高危筛查队列中回顾性报道了[42]在56/1 866个基线筛查扫描中发现了76个NSNs (患病率3%;层厚0.75 mm),平均随访50±7.3个月,只有13个结节是前瞻性确定的,40/48 (83%)pGGOs分解、尺寸上减小或保持稳定,16/28(57%) psGGOs分解或保持稳定。总体而言,74% NSNs分解、减少或保持稳定,26%出现进展,其中有一个psGGO(2%)被证实为肺腺癌。

总之,50%~70%通过现代薄层CT扫描发现的NSNs是短暂存在的,但目前仍不能预测哪些NSN持续存在。研究数据显示:西方与亚洲人群在NSN发病率上有实质性差异。鉴于非实性肿瘤增长缓慢[37,43],对于未分解的NSNs,积极监测>2年可能是审慎的[44]。

增长率

一旦得到连续随访扫描结果即可以评估结节的增长情况。一般来说,如果一个实性结节超过2年时间没有增长,那么这个结节是恶性的可能性极小[45],而同时代的文献回顾发现的基础数据(基于从1950年代开始CXR研究)并不那么引人注目[46]。

CT可很好地评估结节的增长情况。假设在指数增长情况下,一个5 mm直径的结节在460天体积倍增时间(VDT)下,一年以后直径会增加到6 mm,2年后会增加到7.2 mm,经过两年的变化,CXR不能够衡量的结节可被CT检测到。然而,可重复的测量是困难的,在这项研究中[47]阅片者测量的结节平均值的95%置信区间(CIs)为8.5±1.73 mm。使用计算机软件半自动容积测量可能具有良好的重复性和精确度[48,49],这也是NELSON试验[47-50]的测量基础。然而即便这样还是存在误差,例如对小结节、存在运动加工品[51]、结节附着其他结构和NSNs[52]的测量。

对于亚厘米的NCNs,有限的长期随访数据支持,适用于2年稳定期指南。在一项爱尔兰的研究[53]中,83例<10 mmNCNs稳定两年以上,并在随访7年后再次行影像检查,几乎所有结节依然维持不变,然而一个3 mmGGO在4年之内增加到15 mm,随后被诊断为支气管肺泡细胞癌(以前的称谓)。因此在理想的情况下,基于CXR研究确定的两年稳定准则,应该被较大的、当代的CT数据集所验证。

NELSON筛查试验显示出基线尺寸及增长间隔的重要性[54]。891个5~10 mm直径的实性结节被随访一年时间,所有边界光滑和/或附属于裂隙带、胸膜或者血管(接触长度≥结节直径的50%)的743个结节是良性的,并从多因素分析中剔除这些良性结节。对针状的、不规则的或多小分叶的结节进行进一步的分析。10/69个(14.5%)针状的或者边缘不规则的结节与6/168(3.6%)个多小分叶的结节被判定为恶性。在基线情况下,恶性肿瘤的唯一预测因子是结节的体积≥130 mm3(OR 6.3;95%可信区间:1.7-23.0)。随访3个月时基线体积、VDT<400天是重要的预测因子(OR 4.9,95%可信区间:1.2-20.1;OR 15.6,95%置信区间:4.5-53.5);随访一年时,只有VDT是预测因子(OR 213.3,95% CI:18.7-24.30)。很少有结节边缘或者形状的变化持续12个月,所以这些特点都无法从良性结节中区分恶性肿瘤结节[55]。

其他的形态学特征

Diederich[56]在一项133个连续性分解的肺结节的研究中发现,分解与非分解的肺结节在人口学与形态学特征上有很大程度的交叠,以致人口学及形态学的这些特点很难应用于预测2年以上的随访结果。

Takashima经过对一组患者两年随访后指出:良性结节的特点(结节直径≤10 mm,共25例癌症患者)为多边形、位于胸膜下、固体衰减和延伸(更高的长轴与短轴直径比)[57]。对98/146连续筛查对象中检测发现的234个类似结节长期随访,结果分析显示(间隙周围并具有以下任何一个特点:多边形形状,长轴与短轴直径比>1.78,外围位置,血管附着)一半的研究对象是多发的,直径范围从1~13 mm,大多是三角形或椭圆形(86%),隆突以下(84%)和有一个隔连接(73%)[58]。139个筛查对象在随访7.5年之后,没有间隙周围结节发展成癌症。这些类型的结节最可能代表肺内淋巴结,然而这些研究都没有被病理证实。

由于筛查试验研究的低阳性预测值,很难预测哪个结节可能是恶性的;在这两项研究中,对于患病率1%~2%人群的肺结节,如果放射科医生指定为“可疑”或大尺寸或VDT<400天,恶性结节的阳性预测值只有35%左右[50,59]。

结节处置方案

LDCT结节管理方案反映了恶性肿瘤的大小和增长率之间的联系。这个方案来源于三个大型研究,表1概括了NLST、NELSON、I-ELCAP三个研究[52,60,61]。这些方案已分别应用于26 722、7 557和31 567个筛查对象,虽然I-ELCAP没有对照组。尺寸范围的定义略有不同,但一般来说“微结节”(通常小于4~5 mm直径)随访12个月,大结节(>10-15 mm直径)即刻进行进一步检查,中等大小结节患者随访直至确定其增长。多数的研究采用线性方法测量结节的大小,但NELSON研究采用容积测量方法[50]。回顾性分析I-ELCAP研究数据表明:定义一个阳性的基线扫描阈值可能太宽泛;把阈值增加到7~8 mm(最大测量直径与宽度的均值)可能减小假阳性的概率,随之可筛查出50%~68%的阳性病例,但是有5%~6%真阳性病例的诊断被延迟。迄今为止,只有NLST方案被证明能降低肺癌死亡率。

Full table

非结节(偶然)发现(IFs)

IFs如冠状动脉钙化(CAC)、肺气肿、甲状腺结节很常见,但检出率取决于研究的定义和记录的方案。一个NELSON子研究(n=1 929)发现如果IF率为81%,6%的参与者接受后续随访,只有1%有临床意义的发现,这引发了激烈的争论,反对系统寻找IFs[63]。加拿大的一项研究(n=4 073)发现,IFs发现率大约为19%,大约对一半进行了随访,0.8%需要即刻采取措施[64]。

LDCT筛查可能是一个发现其他疾病的机会,如胸部CT发现CAC、慢性阻塞性肺疾病(COPD)和骨质疏松症[65,66]。这可能会增加成本效益并提供更好的全球性结果,但目前尚未经研究证实。放射科医生通过CT扫描发现肺气肿似乎是一个独立增加的肺癌风险(OR 2.1)[67],可能对确定基线扫描以后筛查频率有潜在的帮助[68](即对有可视化监测到的肺气肿进行更频繁的筛查),但是这个假说还有待验证。

CAC作为心脏事件的一个危险标记[69],可能是最重要的IFs。世界范围内,每年估计80万人因为吸烟死于急性心脏病发作[70]。ELCAP的调查人员在4250例筛查中发现了64%不同程度的CAC[71]。他们开发了一个简单的可视化的评分系统,并在第二个8782例筛查队列中对心血管死亡风险进行分层,该队列中位随访时间为6年[72]。NELSON研究中的958个研究对象在随访21个月后,显示出逐渐增多的CAC,并在全因死亡率方面显示出更高的风险比[73]。但是这些发现似乎没有在NLST数据里有所反映,约75%死亡人数来自于非肺癌原因[13]。死亡人数中LDCT组心血管疾病占486/1 865(26.1%),CXR组占470/1 991(23.6%)。当将肺癌死亡从比较中移除,LDCT组死亡率降低6.7%,失去了统计学意义(3.2%,P=0.28),这表明降低全因死亡率的核心是降低肺癌死亡率[13]。临床上重要的IFs在7.5%的扫描中被确定,尽管CAC患病率的细节和随访情况尚未报道,似乎不太可能通过LDCT筛选来确定CAC对心血管病死率的显著影响。

因而IFs虽然常见但是很少有临床意义。过度的调查IFs将增加下游调查与随访筛查成本,故应该进行成本分析。在筛查试验研究中进一步分析CAC和其他情况是必要的。

LDCT-效果筛选

观察性研究

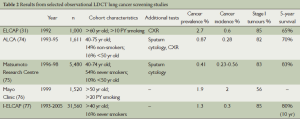

最早的LDCT筛选的研究来自美国和日本的观察性队列研究(表2)。ELCAP研究表明CT的敏感性似乎是CXR的3~4倍,大多数肿瘤处于Ⅰ期。入选标准多变。这些研究招募年轻的参与者(<50岁)和不吸烟者,具有较低的患病率和/或发病率。例如,在日本的研究(75年)中,大多数的筛查者从未吸烟,癌症发病率仅为0.4%,而ECLAP研究为2.7%[31]。这些结果凸显了招募高风险人群的重要性。随后大多数研究遵循ELCAP策略招募老年吸烟者。危险分层是目前的研究热点并将在稍后继续讨论。

Full table

虽然这些研究很有前途,但这些研究缺乏对照组,因而无法估计病死率获益。生存率可作为有效性的替代指标,易受到一些偏倚的影响,故不能被用来证明筛查有效性(框2),各研究的死亡率的显著差异引发了激烈的争论[78-80]。

Full table

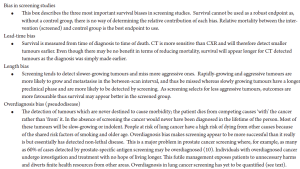

随机对照试验

表3总结了LDCT筛查的随机对照试验。两个试验:NLST(美国)和NELSON(荷兰/比利时)有足够的统计效能检测肺癌死亡率。一些研究者正在计划对较小的欧洲研究进行荟萃分析[93]。所有的欧洲研究(除了Depiscan和DANTE研究)随机分为LDCT筛查及未进行筛查组,后者是目前的标准医疗模式。

Full table

到目前为止,最重要的RCT结果来自于NLST研究[13]。这个具有里程碑意义的研究将53 454名高危志愿者随机分到CXR或LDCT组并进行三轮筛查(基线、1年和2年),中位随访时间为6.5年。这些志愿者的入选标准包括:目前或者既往吸烟>30包/年(戒烟不超过15年),过去5年中没有肺部或其他癌症病史,目前没有症状表明肺癌;过去18个月没有进行胸部CT检查。这项研究显示,在LDCT组肺特异的死亡率相对减少20.0%(95% CI:6.8-26.7;P=0.004)。

尽管这是一个阳性的结果,仍然存在一些特别普遍和值得探讨的问题。NLST的作者宣称他们的数据单独并且不充分,难以做出肺癌筛查的推荐[13],来自于国际研究协会肺癌(IASLC)工作组关于肺癌CT筛查的状况声明,提醒我们对筛选获益、成本和潜在危害必须结合“文化环境”来确定,即如果阳性结果出现在美国的研究中,可能并不能直接转换到其他国家或医疗保健系统[94]。此外,必须要考虑下面所讨论的筛选的负面影响和知识空白。

筛查依从性

好的依从性对大规模筛查试验是否获得成功很关键。在随访的第二年,NLST研究中95%的对象完成了三轮筛查,NELSON有97%的对象完成了三轮筛查。长期观察研究报告5年随访率为80%,7年随访率为86%[76,95]。如何把这些结果应用于现实还不得而知。

下游医疗措施的应用

阳性的扫描和偶然发现需要临床和影像学随访。初次筛查后随访时,前6个月中医疗措施的使用可能上升,但筛查后6~12个月回到基线水平,并可能出现独立的结果(即阴性的、不确定的或可疑的结果)[96]。虽然这个研究发现使就医患者增加了50%,但是按绝对值计算,这只意味着每个参与者增加了一个额外的就医[96]。

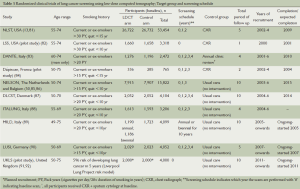

成本效益

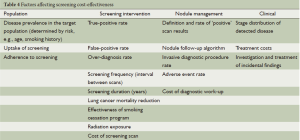

成本效益是筛查试验进行的一个基本要求。它取决于一个复杂的混合因素,不同的项目和国家间差异很大(表4)。预算相差很大取决于潜在的假设和使用的模型,这使得结论很难描绘[97]。使用NLST数据,Goulart估计如果75%的符合条件的美国人接受筛查,避免一个肺癌患者死亡的成本将是240 000美元[98]。McMahon的分析特别注意结合筛查和戒烟预算模型的应用[99]。在一个年龄为50岁左右同时戒烟率较背景戒烟率翻倍的队列中,预算的成本每质量调整生命年(QALY)可能会低于75 000美元。从医疗保险视角预算成本是令人满意的[100];筛查50~64岁高危人群,每个投保者每月仅花费1美元,每生命年成本将低于19 000美元。

Full table

到目前为止,多样化建模方法和基本假设导致了成本效益估算的很大差异。NLST最后分析结果尚未被报道,仍然在同行评审的过程中,但结果被大家所期待。采用增量成本效果比(ICER) 模型估算初步的数据[101]表明这将是符合成本效益的,大约72 900美元/QALY。

筛查的负面效应

任何疾病筛查都具有风险和益处。风险和利益的平衡有助于确定筛检的总体有效性和可接受性。主要的负面影响将在下面讨论。

辐射

电离辐射可引起癌症并且没有较低的“剂量”门槛,这是公认的,不过绝对风险水平仍在讨论中[102,103]。根据ALARA原则,应尽量减少辐射剂量 (“尽可能低至合理”)[104],尤其当筛选无症状健康者时更为重要。CT辐射剂量取决于许多因素,包括管电流、管电压,使用过滤器和扫描长度(z轴)。在筛查研究中最常见的方式是:根据患者体重通过调整管电流(毫安级,mA)[105]来限制剂量。这可能会降低图像质量,因为图像噪声(颗粒状的斑点)与辐射剂量的平方根成反比。幸运的是,充满气体的肺实质与肺软组织之间固有的高对比,意味着肺结节可以被很好地观察。筛查CT平均有效剂量可从8毫西弗(标准胸部CT)减少到约为1.5毫西弗,而没有显著降低图像的质量和分辨率[13,106,107]。尽管可导致更多的噪声,但低辐射剂量已被证明能够提供足够的诊断图像,因而也是当前筛选的标准[108-110]。总辐射剂量可以将随访CT范围限定在结节周围感兴趣区域,而不是覆盖整个胸部,即所谓的“有限”LDCT[111]。

吸烟与电离辐射表现出协同交互作用。按绝对值计算因LDCT罹患癌症的风险很小,也许只增加0.85%风险(95% CI:0.28-2.2%),相比之下,最糟糕的情况是:一个50多岁的女性烟民连续接受25年LDCT扫描,这种情况有17%的风险发展为肺癌[112]。贝灵顿·德·冈萨雷斯估计50岁的烟民死于因LDCT筛查的肺癌风险是2/10 000(男性)、5/10 000(女性)。另外估计每筛查10000名妇女,可能筛查出3例乳腺癌[113]。NLST估计:减少1例因肺癌死亡的患者需要筛查(NNS)320人,相当于减少30例死亡/10 000筛查[13]。辐射伤害要好过癌症诱导发生之后,因被延误诊断而要在短期内进行挽救生命的治疗。ITALUNG研究得出了类似的结论,每筛查10 000人估计1.1超额死亡,与此对应,每筛查10000人大约挽救了15~100人的生命(男性和女性分别估算),假设筛查降低了20%的死亡率[114]。因此LDCT的辐射风险–效益比率对老年吸烟者显得相当有利。

副反应

LDCT调查结果可能导致许多不良事件。25%~50%的筛查可能检测到一个或多个结节,存在一大群处于风险中的潜在的患者。在NLST累积的阳性筛查率是39.1%,尽管指南已经发现在美国医院之间[115],肺结节活检率(14.7-36.2每100 000名成年人)和并发症发生率(116年)有巨大差异。出血、需要间断导管引流(ICC)的气胸的风险分别为1.0%和6.6%。并发症发生与住院时间增加和呼吸衰竭有关。风险最高的是烟民、年龄在60岁到69岁、患有慢性阻塞性肺病患者,即筛查试验的目标人群。LDCT筛查研究副反应发生率可能略高于上述研究,但这恰恰反映了更严格的、前瞻性的报告。似乎没有标准的方式定义或报告不良事件数据,这使得一些研究难以进行直接比较。“事件的数量/10 000筛查”可能是一个有用的便于交叉研究比较的度量标准。

一项有4 782人参与的使用I-ELCAP方案的筛查研究[117],公布的活检率为2.6%(n=127),包括110例CT引导下经皮细针穿刺活检(CT-FNA)。13%的CT-FNAs并发中等到大量气胸,并需要ICC或住院治疗。16%的活检标本最后确定为良性疾病[117]。NELSON报道,使用一个基于体积测量的研究方案,需手术诊断的比例,第一轮随访为1.2%、第二轮为0.8%,每一轮分别有32/92(35%)和13/61(21%)证明是良性疾病。很少进行CT-FNAs:第一轮5/13CT-FNAs,第二轮3/3FNA证明是良性疾病。两轮支气管镜检查诊断的癌症111/247(45%)低于预期,可能反映了周围型肿瘤的发生情况。并发症发生率没有报道[50]。

PLuSS的研究[118] 使用一个内部方案筛查3642名参与者。82人(2.3%)接受手术(胸廓切开术),28人(34%)有良性疾病。对于不确定的肺结节,研究人员沿引了“一个明显倾向于激进的干预措施的社区偏倚”。

在基线水平,NLST研究中LDCT组有27.3%的阳性扫描结果[13]。155/7 191参与者接受了经皮诊断(120例CT-FNA),297例(4.1%的阳性扫描)接受诊断性手术(开胸手术、胸腔镜、纵隔镜检查或纵隔切开术),包括197例开胸手术。在所有三轮筛查中(75 126个筛查),LDCT组164/673(24%)为肺癌诊断。191/673(29%)的参与者侵入式诊断后至少经历了一次手术并发症;80(12%)例归类为严重并发症。99例中只有14个(14%)参与者接受了针吸活检,他们的侵入性诊断过程经历了一个或多个并发症但没有严重并发症。16个参与者(10例为肺癌)在侵入性诊断后60天内死亡,但不能确定死亡是否直接与侵入性诊断相关。换句话说每10 000筛查者中,有33例在诊断性评估过程中遭受了严重的并发症,但任何支气管镜检查或穿刺活检诊断后并发症发生率较低,分别为1.5例和0.7例每10 000个筛查;发生在诊断评价2个月内的死亡率为8/10 000[16]。I-ELCAP没有报告其诊断后的并发症发生率。

CT-FNA的并发症发生率为13%~14%,是相对安全的,其活检结果与切除病理标本组织学检查保持良好的一致性[119]。另一方面支气管镜检查虽然也相对安全,但其对外围的癌症筛查检测可能仅有小的获益,尽管新技术,比如支气管内超声和电磁导航也许能够提高收益[120,121]。手术过程中重大并发症的发生率为12%,但约20%~35%的病例最终诊断为良性疾病。这将影响成本效益。

虽然最终决定切除不确定的结节是一种临床决策,鉴于筛查试验报告的高比例的良性疾病率,手术切除之前获得一个阳性的组织诊断是可取的。NELSON研究表明,由良性疾病引起的超过三个月时间确切增长的比例多达三分之一。到目前为止,在大多数高级专家中心进行的研究中,CT-FNA作为小的周围型病变的初始诊断程序。通过严格的管理和质量保证,降低不必要的活检和切除是可能的。

保留肺叶手术

如Blasburg等人综述的那样,随着技术手段的进步,对体积较小肿瘤的认知和它们良好的预后,尤其是主要含有GGO成分的小肿瘤,和正处在风险之中的逐渐发展的亚肿瘤,逐渐倾向于行保留肺叶的手术(解剖肺段切除术或肺楔形切除术)替代肺叶切除术[122]。两个正在招募患者的随机对照试验很有希望能够回答这个重要的问题[CALGB 140503和JCOG0802/WJOG4607L[123]]。

生存质量

三项研究报道了来自于大约2 500筛查患者的一般健康相关的生存质量(HRQoL)、焦虑和肺癌特定抑郁的研究数据[124-126]。所有的发现均来自于获得一个不确定的或可疑的筛查结果时产生的瞬变消极的心理作用。这些效应消退较快,因而HRQoL在基线水平与12~24个月随访之间没有显著差异。NELSON研究发现,一半参与者感觉等待他们的基线CT扫描结果是“令人不安的”,但这一个不确定的结果在第二轮筛查时对HRQoL没有影响。这表明减少测试结果的等待时间是有益的,参与者很快接受一个不确定的扫描结果,并不一定保证会有高焦虑[124,127]。

戒烟

戒烟是非常重要的,不仅降低没有癌症的参与者的风险,也可能改善早期确诊为肺癌的患者的预后[128]。肺癌筛查可能成为一个“宣教契机”,增加了烟民戒烟的动力,特别是当参与者收到异常CT扫描报告时[129-131]。成功的戒烟计划也可能使筛查更划算[99],戒烟在几个方面辅助“增加筛查试验的价值”,它应该是任何肺癌筛查试验的一个核心组分。

知识缺口

尽管NLST研究获得了阳性结果,研究试验外的筛查,应该在仔细的风险评估之前,并在受控环境中进行,推荐筛查之前仔细分析所有结果以确保质量。两个国际的研究小组已经考虑到当前证据的状态和未来发展方向。那些需要解决的重点包括:①如何优化识别高危个体;②筛查方案(比如筛查间隔时间、筛查几轮);③阳性结果的定义;④不确定结节的处理;⑤对可疑结节的诊断和治疗;⑥综合的戒烟项目;⑦早期检测生物标记物在个人肺癌风险评估中的角色;⑧过度诊断发生率。重要的步骤将是设备和图像质量标准化,结节分析和解释,参与者随访和结果报告[93,132]。这些领域将在下面讨论。

过度诊断

过度诊断很难确定(见框2定义)。据NLST研究,通过对LDCT组与对照组的相对差异估计,过度诊断率在13%左右,LDCT组检测到1 060例癌症,对照组中检测到941例癌症[13]。然而这个数字已经被指责为过于低估[133]。指责的基础为,适当的分母应为对照组在筛查期间实际检测到的肺癌的数量(n=470),而不是对照组最后随访到的肺癌数量(n=941)。如果这样计算,过度诊断率接近25%,与梅奥医院基于体积倍增时间的LDCT研究报道的过度诊断率类似[37]。但是即使是这个数字,也可能低估了过度诊断率,因为CXR筛查组本身也可能受到过度诊断[133]。针对这个问题,符合NLST研究入组标准的PLCO队列研究的亚组分析(n=30 321)发现,在CXR组和非筛查组中,具有类似的肺癌病例的数量 (518和520,分别在6年随访期内)[12]。似乎只有欧洲筛查试验与常规治疗比较(即没有筛查)能够给一个真正的过度诊断率的估计值[90]。因此这个问题目前仍未得到回答。

筛查间隔与随访期限

适当的筛查间隔时间应在疾病控制与筛查成本间获得一个有利的比率[134]。最近发表的MILD研究结果来自于一个纳入了4 099例参与者的三臂的随机对照试验:观察 vs. 每年筛查 vs. 两年筛查一次[89]。两个LDCT组的临床分期和切除率相似。每年筛查一次的LDCT组累计5年肺癌发病率高于每两年筛查一次的LDCT组和对照组(620/100 000 vs. 457和311,P=0.036)。每个LDCT筛查方案的依从率>95%,但平均随访时间只有4.4年。招募的病例显著少于计划的10 000例参与者,意味着该研究没有足够的检验效力检测死亡率的差异。同时筛查与非筛查组特征的差异(如吸烟状态、吸烟强度和肺功能)引起人们对随机化的充分程度的质疑[135]。这个研究的长期随访结果可能包含更多有用的信息。NELSON研究中,在第1年(基线)、第2年和第4年分别筛查研究对象,即第二次和第三次扫描有为期两年的差距,当4年随访结果公布后可以确定一个最佳筛查间隔。正如前面提到的,基线扫描时的数据收集(比如有无放射肺气肿)可能在确定风险、最佳筛查间隔是很有用的[68]。关于筛查的持续时间,NLST研究中在阳性筛查试验后,LDCT组共检测到649例癌症患者(270例在基线时,168例和211例分别在第1年和第2年),有367例参与者在筛查或诊断完成后才被诊断(平均随访6.5年)。这表明癌症检测率(即癌症风险)随着时间的持续下降不明显,因此持续的筛查是必要的。因此当前的指南建议每年筛查,直到74岁(14,16)或79岁[15]。

招募

各研究间招募患者的策略有差异,最常见的是直接邮寄和/或媒体发布,但一些使用全科医生转诊[84,88]。与不吸烟者相比,吸烟者明显地具有更少的反对风险,至少在他们的健康方面是如此考虑。决定进入一个筛查试验是一种复杂因素的平衡,包括可接受的筛查方法、风险感知、利他主义、利己主义[136]。不可避免的是,志愿者在任何试验都是自我选择的,并存在有利“健康志愿者”效应。这可能会导致过度乐观的结果(如更好的筛查并发症,较高的戒烟率)或过度悲观的结果(如较低的有效性,因为低风险的个人筛查利益)。

NLST和NELSON研究发现,他们的研究人群与一般符合入组条件的人群存在一些差异:参与者更年轻,而且较小的可能是吸烟者,并且有较高的受教育水平(代表社会经济地位)。这些差异被认为是次要的,这意味着一个重要的健康志愿者效应是不可能的[81,137]。

风险分级

一个基本的风险分级方法已经应用于大多数研究,即采用ELCAP研究筛查老年吸烟者所采取的策略。尽管年龄和吸烟占据了绝大多数的肺癌风险,其他风险因素,如家族病史、社会经济地位、职业暴露和COPD也是公认的危险因素[138]。进一步使用其他现成的信息进行风险分层,从而排除低风险者,可以提高筛查效率[139]。不同的模型已经被提出,最大的模型来自PLCO试验数据,最近已经进行了更新[140,141]。对该模型的PLCO数据集,回顾性分析发现,这是更有效的方式,相比于以标准的年龄和吸烟建立的NLST入组标准,灵敏度从71%提高到83%(P<0.001),阳性预测值从3.4%提高到4.0%(P=0.01),并保持了特异性(各占63%)。使用风险模型来选择筛查,至少会错过少于41.3%的肺癌[141]。英国另一个前瞻性评估风险模型的肺癌筛查试验正在开展[142]。危险分层通过增加筛选人群肺癌患病率和发病率并减少假阳性检查结果,可提高筛选效率和成本效益。尽管风险分层直观上可以理解,但它还没有被实验证明,因此筛查指南建议推荐有分歧[发表风险模型[15],非正式的风险评估,不推荐的]。

筛查实施

从严格控制的研究中获得的普遍化的结果来看,为了能够准确地跟踪和评估随着时间推移结节的变化,大规模筛查需要统一标准的和高水平的质量控制[132]。肺癌筛查不仅仅是简单地提供一个CT服务,而是需要一个长期广泛的基础设施保证,包括:有条件招募、质量改进、筛查的劳动力/设施、诊断和治疗、卫生职业培训、参与者信息和支持。为确保满足高医疗标准及提供一个一致并可接受的方法,持续的评估和监测项目是至关重要的[134,143]。

未来的研究

微创、廉价的检测方式辨认,最有可能从筛查中获益的是那些处于最高肺癌风险的个体,从恶性肿瘤中区分良性结节的筛查检测,将代表肺癌结节筛查的主要进展。在这方面有前途的新技术包括:分析血液循环微小RNA和呼出气体的挥发性有机化合物检测[144-146]。最近的筛查研究方案中已经包括了生物标志物收集,所以我们可以期待在不久的将来将会有令人耳目一新的发现。

结论

具有里程碑意义的NLST的研究结果证实了一个长期存在的公认的信念:肺癌筛查可以挽救更多的生命。可以理解的是,LDCT作为一种新的干预手段,推广到美国以外的情况仍然存在许多问题。在未来的几年里,进一步分析NLST数据和其他研究的成熟结果,能够填补这些知识空白,并且将使肺癌社区逐渐形成,并逐渐完善我们的筛查方式。

Acknowledgements

We thank the study volunteers and staff of The Prince Charles Hospital for their involvement in our research program and the Queensland Lung Cancer Screening Study research team.

Funding: This work was supported by National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) project grants, NHMRC Practitioner Fellowship (KF), NHMRC Career Development Award (IY), Cancer Council Queensland Senior Research Fellowship (KF), Cancer Council Queensland project grants, Queensland Smart State project grants, Office of Health and Medical Research (OHMR) project grants, The Prince Charles Hospital Foundation, NHMRC Postgraduate Medical Scholarship (HM), University of Queensland PhD Scholarship (HM).

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ferlay J, Shin H, Bray F, et al. GLOBOCAN 2008. Available online:

- Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 2011;61:69-90. [PubMed]

- Gu D, Kelly TN, Wu X, et al. Mortality attributable to smoking in China. N Engl J Med 2009;360:150-9. [PubMed]

- Sant M, Allemani C, Santaquilani M, et al. EUROCARE-4. Survival of cancer patients diagnosed in 1995-1999. Results and commentary. Eur J Cancer 2009;45:931-91. [PubMed]

- Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975-2008. Available online:

- Sankaranarayanan R, Swaminathan R, Brenner H, et al. Cancer survival in Africa, Asia, and Central America: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol 2010;11:165-73. [PubMed]

- Scott WJ, Howington J, Feigenberg S, et al. Treatment of non-small cell lung cancer stage I and stage II*. Chest 2007;132:234S-242S. [PubMed]

- Goldstraw P, Crowley J, Chansky K, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: proposals for the revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the TNM classification of malignant tumours. J Thorac Oncol 2007;2:706-14. [PubMed]

- Wilson JMG, Jungner G. eds. Principles and practice of screening for disease. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1968.

- Welch HG, Black WC. Overdiagnosis in Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2010;102:605-13. [PubMed]

- Manser RL, Irving LB, Stone C, et al. Screening for lung cancer. Cochrane Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;(1):CD001991.

- Oken MM, Hocking WG, Kvale PA, et al. Screening by chest radiograph and lung cancer mortality. JAMA 2011;306:1865-73. [PubMed]

- National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med 2011;365:395-409. [PubMed]

- Wood DE, Eapen GA, Ettinger DS, et al. Lung cancer screening. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2012;10:240-65. [PubMed]

- Jaklitsch MT, Jacobson FL, Austin JH, et al. The American Association for Thoracic Surgery guidelines for lung cancer screening using low-dose computed tomography scans for lung cancer survivors and other high-risk groups. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012;144:33-8. [PubMed]

- Bach PB, Mirkin JN, Oliver TK, et al. Benefits and harms of CT screening for lung cancer: a systematic review. JAMA 2012;307:2418-29. [PubMed]

- Force UPST. US preventive services task force. Draft recommendation statement. Available online:

- Hansell DM, Bankier A, MacMahon H, et al. Fleischner society: glossary of terms for thoracic imaging. Radiology 2008;246:697-722. [PubMed]

- Armato SG, Roberts RY, Kocherginsky M, et al. Assessment of radiologist performance in the detection of lung nodules: dependence on the definition of “truth”. Acad Radiol 2009;16:28-38. [PubMed]

- Gierada DS, Pilgram TK, Ford M, et al. Lung cancer: interobserver agreement on interpretation of pulmonary findings at low-dose CT screening. Radiology 2008;246:265-72. [PubMed]

- Swensen SJ, Jett JR, Sloan JA, et al. Screening for lung cancer with low-dose spiral computed tomography. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;165:508-13. [PubMed]

- Wormanns D, Ludwig K, Beyer F, et al. Detection of pulmonary nodules at multirow-detector CT: effectiveness of double reading to improve sensitivity at standard-dose and low-dose chest CT. Eur Radiol 2005;15:14-22. [PubMed]

- Jankowski A, Martinelli T, Timsit JF, et al. Pulmonary nodule detection on MDCT images: evaluation of diagnostic performance using thin axial images, maximum intensity projections, and computer-assisted detection. Eur Radiol 2007;17:3148-56. [PubMed]

- Coakley FV, Cohen MD, Johnson MS, et al. Maximum intensity projection images in the detection of simulated pulmonary nodules by spiral CT. Br J Radiol 1998;71:135-40. [PubMed]

- Kawel N, Seifert B, Luetolf M, et al. Effect of slab thickness on the CT detection of pulmonary nodules: use of sliding thin-slab maximum intensity projection and volume rendering. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2009;192:1324-9. [PubMed]

- Armato SG 3rd, Li F, Giger ML, et al. Lung cancer: performance of automated lung nodule detection applied to cancers missed in a CT screening program. Radiology 2002;225:685-92. [PubMed]

- Yuan R, Vos PM, Cooperberg PL. Computer-aided detection in screening CT for pulmonary nodules. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2006;186:1280-7. [PubMed]

- Saba L, Caddeo G, Mallarini G. Computer-aided detection of pulmonary nodules in computed tomography: analysis and review of the literature. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2007;31:611-9. [PubMed]

- Midthun DE, Swensen SJ, Jett JR, et al. Evaluation of nodules detected by screening for lung cancer with low dose spiral computed tomography. Lung Cancer 2003;41:S40.

- Gohagan J, Marcus P, Fagerstrom R, et al. Baseline findings of a randomized feasibility trial of lung cancer screening with spiral CT scan vs chest radiograph: the Lung Screening Study of the National Cancer Institute. Chest 2004;126:114-21. [PubMed]

- Henschke CI, McCauley DI, Yankelevitz DF, et al. Early Lung Cancer Action Project: overall design and findings from baseline screening. Lancet 1999;354:99-105. [PubMed]

- The National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Results of initial low-dose computed tomographic screening for lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1980-91. [PubMed]

- Bellomi M, Veronesi G, Rampinelli C, et al. Evolution of lung nodules < or =5 mm detected with low-dose CT in asymptomatic smokers. Br J Radiol 2007;80:708-12. [PubMed]

- Erasmus JJ, Connolly JE, McAdams HP, et al. Solitary pulmonary nodules: part I. morphologic evaluation for differentiation of benign and malignant lesions. Radiographics 2000;20:43-58. [PubMed]

- Henschke CI, Yankelevitz DF, Mirtcheva R, et al. CT screening for lung cancer: frequency and significance of part-solid and nonsolid nodules. Am J Roentgenol 2002;178:1053-7. [PubMed]

- Kakinuma R, Ohmatsu H, Kaneko M, et al. Progression of focal pure ground-glass opacity detected by low-dose helical computed tomography screening for lung cancer. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2004;28:17-23. [PubMed]

- Lindell RM, Hartman TE, Swensen SJ, et al. Five-year lung cancer screening experience: CT appearance, growth rate, location, and histologic features of 61 lung cancers. Radiology 2007;242:555-62. [PubMed]

- Aoki T, Nakata H, Watanabe H, et al. Evolution of peripheral lung adenocarcinomas: CT findings correlated with histology and tumor doubling time. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2000;174:763-8. [PubMed]

- Felix L, Serra-Tosio G, Lantuejoul S, et al. CT characteristics of resolving ground-glass opacities in a lung cancer screening programme. Eur J Radiol 2011;77:410-6. [PubMed]

- Oh JY, Kwon SY, Yoon HI, et al. Clinical significance of a solitary ground-glass opacity (GGO) lesion of the lung detected by chest CT. Lung Cancer 2007;55:67-73. [PubMed]

- Lee SM, Park C, Goo J, et al. Transient part-solid nodules detected at screening thin-section CT for lung cancer: comparison with persistent part-solid nodules. Radiology 2010;255:242-51. [PubMed]

- Mario M, Nicola S, Carmelinda M, et al. Long-term surveillance of ground-glass nodules: evidence from the mild trial. J Thorac Oncol 2012;7:1541-6. [PubMed]

- Hasegawa M, Sone S, Takashima S, et al. Growth rate of small lung cancers detected on mass CT screening. Br J Radiol 2000;73:1252-9. [PubMed]

- Godoy MC, Naidich DP. Overview and strategic management of subsolid pulmonary nodules. J Thorac Imaging 2012;27:240-8. [PubMed]

- MacMahon H, Austin JH, Gamsu G, et al. Guidelines for management of small pulmonary nodules detected on CT scans: a statement from the Fleischner Society. Radiology 2005;237:395-400. [PubMed]

- Yankelevitz DF, Henschke CI. Does 2-year stability imply that pulmonary nodules are benign? AJR Am J Roentgenol 1997;168:325-8. [PubMed]

- Revel MP, Bissery A, Bienvenu M, et al. Are two-dimensional CT measurements of small noncalcified pulmonary nodules reliable? Radiology 2004;231:453-8. [PubMed]

- Revel MP, Lefort C, Bissery A, et al. Pulmonary nodules: preliminary experience with three-dimensional evaluation. Radiology 2004;231:459-66. [PubMed]

- Yankelevitz DF, Reeves AP, Kostis WJ, et al. Small pulmonary nodules: volumetrically determined growth rates based on CT evaluation. Radiology 2000;217:251-6. [PubMed]

- van Klaveren RJ, Oudkerk M, Prokop M, et al. Management of lung nodules detected by volume CT scanning. N Engl J Med 2009;361:2221-9. [PubMed]

- Kostis WJ, Yankelevitz D, Reeves A, et al. Small pulmonary nodules: reproducibility of three-dimensional volumetric measurement and estimation of time to follow-up CT. Radiology 2004;231:446-52. [PubMed]

- Xu DM, Gietema H, de Koning H, et al. Nodule management protocol of the NELSON randomised lung cancer screening trial. Lung Cancer 2006;54:177-84. [PubMed]

- Slattery MM, Foley C, Kenny D, et al. Long-term follow-up of non-calcified pulmonary nodules (<10 mm) identified during low-dose CT screening for lung cancer. Eur Radiol 2012;22:1923-8. [PubMed]

- Xu DM, van der Zaag-Loonen HJ, Oudkerk M, et al. Smooth or attached solid indeterminate nodules detected at baseline CT screening in the NELSON study: cancer risk during 1 year of follow-up. Radiology 2009;250:264-72. [PubMed]

- Xu DM, van Klaveren RJ, de Bock GH, et al. Role of baseline nodule density and changes in density and nodule features in the discrimination between benign and malignant solid indeterminate pulmonary nodules. Eur J Radiol 2009;70:492-8. [PubMed]

- Diederich S, Hansen J, Wormanns D. Resolving small pulmonary nodules: CT features. Eur Radiol 2005;15:2064-9. [PubMed]

- Takashima S, Sone S, Li F, et al. Small solitary pulmonary nodules (1 cm) detected at population-based CT screening for lung cancer: reliable high-resolution CT features of benign lesions. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2003;180:955-64. [PubMed]

- Ahn MI, Gleeson TG, Chan IH, et al. Perifissural nodules seen at CT screening for lung cancer. Radiology 2010;254:949-56. [PubMed]

- Markowitz SB, Miller A, Miller J, et al. Ability of low-dose helical CT to distinguish between benign and malignant noncalcified lung nodules. Chest 2007;131:1028-34. [PubMed]

- ACRIN. ACRIN Protocol. Available online:

- International Early Lung Cancer Action Program. Enrollment and screening protocol. Available online:

- Henschke CI, Yip R, Yankelevitz DF, et al. Definition of a positive test result in computed tomography screening for lung cancer: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:246-52. [PubMed]

- van de Wiel JC, Wang Y, Xu DM, et al. Neglectable benefit of searching for incidental findings in the Dutch-Belgian lung cancer screening trial (NELSON) using low-dose multidetector CT. Eur Radiol 2007;17:1474-82. [PubMed]

- Kucharczyk MJ, Menezes RJ, McGregor A, et al. Assessing the impact of incidental findings in a lung cancer screening study by using low-dose computed tomography. Can Assoc Radiol J 2011;62:141-5. [PubMed]

- Mets OM, de Jong PA, Prokop M. Computed tomographic screening for lung cancer: an opportunity to evaluate other diseases. JAMA 2012;308:1433-4. [PubMed]

- Patel AR, Wedzicha J, Hurst J. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with CT screening. N Engl J Med 2011;365:2035-author reply 2037-8. [PubMed]

- Smith BM, Pinto L, Ezer N, et al. Emphysema detected on computed tomography and risk of lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lung Cancer 2012;77:58-63. [PubMed]

- Maisonneuve P, Bagnardi V, Bellomi M, et al. Lung cancer risk prediction to select smokers for screening CT--a model based on the Italian COSMOS trial. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2011;4:1778-89. [PubMed]

- Waugh N, Black C, Walker S, et al. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of computed tomography screening for coronary artery disease: systematic review. Health Technol Assess 2006;10:iii-iv, ix-x, 1-41.

- Jha P. Avoidable global cancer deaths and total deaths from smoking. Nat Rev Cancer 2009;9:655-64. [PubMed]

- Shemesh J, Henschke CI, Farooqi A, et al. Frequency of coronary artery calcification on low-dose computed tomography screening for lung cancer. Clin Imaging 2006;30:181-5. [PubMed]

- Shemesh J, Henschke CI, Shaham D, et al. Ordinal scoring of coronary artery calcifications on low-dose CT scans of the chest is predictive of death from cardiovascular disease. Radiology 2010;257:541-8. [PubMed]

- Jacobs PC, Gondrie MJ, van der Graaf Y, et al. Coronary artery calcium can predict all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events on low-dose ct screening for lung cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2012;198:505-11. [PubMed]

- Sobue T, Moriyama N, Kaneko M, et al. Screening for lung cancer with low-dose helical computed tomography: anti-lung cancer association project. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:911-20. [PubMed]

- Sone S, Nakayama T, Honda T, et al. Long-term follow-up study of a population-based 1996-1998 mass screening programme for lung cancer using mobile low-dose spiral computed tomography. Lung Cancer 2007;58:329-41. [PubMed]

- Swensen SJ, Jett JR, Hartman TE, et al. CT screening for lung cancer: five-year prospective experience. Radiology 2005;235:259-65. [PubMed]

- The International Early Lung Cancer Action Program I, Henschke CI, Yankelevitz D, et al. Survival of patients with stage I lung cancer detected on CT screening. N Engl J Med 2006;355:1763-71. [PubMed]

- Bach PB, Jett JR, Pastorino U, et al. Computed tomography screening and lung cancer outcomes. JAMA 2007;297:953-61. [PubMed]

- Patz EF Jr, Swensen SJ, Herndon JE. Estimate of lung cancer mortality from low-dose spiral computed tomography screening trials: implications for current mass screening recommendations. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:2202-6. [PubMed]

- Foy M, Yip R, Chen X, et al. Modeling the mortality reduction due to computed tomography screening for lung cancer. Cancer 2011;117:2703-8. [PubMed]

- National Lung Screening Trial Research Team, Aberle DR, Adams AM, et al. Baseline characteristics of participants in the randomized national lung screening trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 2010;102:1771-9. [PubMed]

- Gohagan JK, Marcus PM, Fagerstrom RM, et al. Final results of the lung screening study, a randomized feasibility study of spiral CT versus chest X-ray screening for lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2005;47:9-15. [PubMed]

- Infante M, Cavuto S, Lutman FR, et al. A randomized study of lung cancer screening with spiral computed tomography: three-year results from the DANTE trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;180:445-53. [PubMed]

- Blanchon T, Brechot JM, Grenier PA, et al. Baseline results of the Depiscan study: a French randomized pilot trial of lung cancer screening comparing low dose CT scan (LDCT) and chest X-ray (CXR). Lung Cancer 2007;58:50-8. [PubMed]

- van Iersel CA, de Koning HJ, Draisma G, et al. Risk-based selection from the general population in a screening trial: selection criteria, recruitment and power for the Dutch-Belgian randomised lung cancer multi-slice CT screening trial (NELSON). Int J Cancer 2007;120:868-74. [PubMed]

- Baecke E, de Koning HJ, Otto SJ, et al. Limited contamination in the Dutch-Belgian randomized lung cancer screening trial (NELSON). Lung Cancer 2010;69:66-70. [PubMed]

- Pedersen JH, Ashraf H, Dirksen A, et al. The Danish randomized lung cancer CT screening trial--overall design and results of the prevalence round. J Thorac Oncol 2009;4:608-14. [PubMed]

- Lopes Pegna A, Picozzi G, Mascalchi M, et al. Design, recruitment and baseline results of the ITALUNG trial for lung cancer screening with low-dose CT. Lung Cancer 2009;64:34-40. [PubMed]

- Pastorino U, Rossi M, Rosato V, et al. Annual or biennial CT screening versus observation in heavy smokers: 5-year results of the MILD trial. Eur J Cancer Prev 2012;21:308-15. [PubMed]

- Becker N, Motsch E, Gross ML, et al. Randomized study on early detection of lung cancer with MSCT in Germany: study design and results of the first screening round. Journal of cancer research and clinical oncology 2012;138:1475-86. [PubMed]

- Field JK, Baldwin D, Brain K, et al. CT screening for lung cancer in the UK: position statement by UKLS investigators following the NLST report. Thorax 2011;66:736-7. [PubMed]

- NIHR. Health technology assessment programme. Available online:

- Italian lung cancer CT screening trial workshop. International workshop on randomized lung cancer screening trials; Position statement, Pisa, March 3-4. 2011. Available online:

- International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. IASLC task force on CT screening: position statement. 2011 [cited 01/12/2011]. Available online:

- Veronesi G, Maisonneuve P, Spaggiari L, et al. Long-term outcomes of a pilot CT screening for lung cancer. Ecancermedicalscience 2010;4:186. [PubMed]

- Byrne MM, Koru-Sengul T, Zhao W, et al. Healthcare use after screening for lung cancer. Cancer 2010;116:4793-9. [PubMed]

- Black C, Bagust A, Boland A, et al. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of computed tomography screening for lung cancer: systematic reviews. Health Technol Assess 2006;10:iii-iv, ix-x, 1-90.

- Goulart BHL, Bensink ME, Mummy DG, et al. Lung cancer screening with low-dose computed tomography: costs, national expenditures, and cost-effectiveness. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2012;10:267-75. [PubMed]

- McMahon PM, Kong CY, Bouzan C, et al. Cost-effectiveness of computed tomography screening for lung cancer in the United States. J Thorac Oncol 2011;6:1841-8. [PubMed]

- Pyenson BS, Sander MS, Jiang Y, et al. An actuarial analysis shows that offering lung cancer screening as an insurance benefit would save lives at relatively low cost. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:770-9. [PubMed]

- Black WC. Cost Effectiveness of CT Screening in the National Lung Screening Trial, in 2nd Joint Meeting of the National Cancer Institute Board of Scientific Advisors & National Cancer Advisory Board 2013: Bethseda (Accessed 19 Aug 2013, at ).

- Berrington de González A, Darby S. Risk of cancer from diagnostic X-rays: estimates for the UK and 14 other countries. Lancet 2004;363:345-51. [PubMed]

- Herzog P, Rieger CT. Risk of cancer from diagnostic X-rays. Lancet 2004;363:340-41. [PubMed]

- ICRP. Recommendations of the ICRP. Annals of the ICRP 1977;1:3.

- Kubo T, Lin P-JP, Stiller W, et al. Radiation dose reduction in chest CT: a review. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2008;190:335-43. [PubMed]

- Marshall H, Smith I, Keir B, et al. Radiation dose during lung cancer screening with low-dose computed tomography: how low is low dose? J Thorac Oncol 2010;6.

- Mascalchi M, Mazzoni LN, Falchini M, et al. Dose exposure in the ITALUNG trial of lung cancer screening with low-dose CT. Br J Radiol 2012;85:1134-9. [PubMed]

- Takahashi M, Maguire WM, Ashtari M, et al. Low-dose spiral computed tomography of the thorax: comparison with the standard-dose technique. Invest Radiol 1998;33:68-73. [PubMed]

- Mayo JR, Hartman TE, Lee KS, et al. CT of the chest: minimal tube current required for good image quality with the least radiation dose. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1995;164:603-7. [PubMed]

- Diederich S, Lenzen H, Windmann R, et al. Pulmonary nodules: experimental and clinical studies at low-dose CT. Radiology 1999;213:289-98. [PubMed]

- Marshall HM, Bowman RV, Crossin J, et al. Queensland lung cancer screening study: rationale, design and methods. Intern Med J 2013;43:174-82. [PubMed]

- Brenner DJ. Radiation risks potentially associated with low-dose CT screening of adult smokers for lung cancer. Radiology 2004;231:440-5. [PubMed]

- Berrington de González A, Kim KP, Berg CD. Low-dose lung computed tomography screening before age 55: estimates of the mortality reduction required to outweigh the radiation-induced cancer risk. J Med Screen 2008;15:153-8. [PubMed]

- Mascalchi M, Belli G, Zappa M, et al. Risk-benefit analysis of X-ray exposure associated with lung cancer screening in the Italung-CT trial. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2006;187:421-9. [PubMed]

- Eisenberg RL, Bankier A, Boiselle P. Compliance with Fleischner Society guidelines for management of small lung nodules: a survey of 834 radiologists. Radiology 2010;255:218-24. [PubMed]

- Wiener RS, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S, et al. Population-based risk for complications after transthoracic needle lung biopsy of a pulmonary nodule: an analysis of discharge records. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:137-44. [PubMed]

- Wagnetz U, Menezes RJ, Boerner S, et al. CT screening for lung cancer: implication of lung biopsy recommendations. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2012;198:351-8. [PubMed]

- Wilson DO, Weissfeld JL, Fuhrman CR, et al. The Pittsburgh Lung Screening Study (PLuSS): outcomes within 3 years of a first computed tomography scan. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;178:956-61. [PubMed]

- Vazquez MF, Koizumi JH, Henschke CI, et al. Reliability of cytologic diagnosis of early lung cancer. Cancer 2007;111:252-8. [PubMed]

- Leong S, Ju H, Marshall H, et al. Electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy: a descriptive analysis. J Thorac Dis 2012;4:173-85. [PubMed]

- Steinfort DP, Khor YH, Manser RL, et al. Radial probe endobronchial ultrasound for the diagnosis of peripheral lung cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J 2011;37:902-10. [PubMed]

- Blasberg JD, Pass HI, Donington JS. Sublobar resection: a movement from the Lung Cancer Study Group. J Thorac Oncol 2010;5:1583-93. [PubMed]

- Nakamura K, Saji H, Nakajima R, et al. A phase III randomized trial of lobectomy versus limited resection for small-sized peripheral non-small cell lung cancer (JCOG0802/WJOG4607L). Jpn J Clin Oncol 2010;40:271-4. [PubMed]

- van den Bergh KA, Essink-Bot ML, Borsboom GJ, et al. Long-term effects of lung cancer computed tomography screening on health-related quality of life: the NELSON trial. Eur Respir J 2011;38:154-61. [PubMed]

- Vierikko T, Kivisto S, Jarvenpaa R, et al. Psychological impact of computed tomography screening for lung cancer and occupational pulmonary disease among asbestos-exposed workers. Eur J Cancer Prev 2009;18:203-6. [PubMed]

- Byrne MM, Weissfeld J, Roberts MS. Anxiety, fear of cancer, and perceived risk of cancer following lung cancer screening. Med Decis Making 2008;28:917-25. [PubMed]

- van den Bergh KA, Essink-Bot ML, Bunge EM, et al. Impact of computed tomography screening for lung cancer on participants in a randomized controlled trial (NELSON trial). Cancer 2008;113:396-404. [PubMed]

- Parsons A, Daley A, Begh R, et al. Influence of smoking cessation after diagnosis of early stage lung cancer on prognosis: systematic review of observational studies with meta-analysis. BMJ 2010;340:b5569. [PubMed]

- Ostroff JS, Buckshee N, Mancuso CA, et al. Smoking cessation following CT screening for early detection of lung cancer. Prev Med 2001;33:613-21. [PubMed]

- Cox LS, Clark MM, Jett JR, et al. Change in smoking status after spiral chest computed tomography scan screening. Cancer 2003;98:2495-501. [PubMed]

- Styn MA, Land SR, Perkins KA, et al. Smoking behavior 1 year after computed tomography screening for lung cancer: effect of physician referral for abnormal CT findings. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2009;18:3484-9. [PubMed]

- Field JK, Smith RA, Aberle DR, et al. International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Computed Tomography Screening Workshop 2011 report. J Thorac Oncol 2012;7:10-9. [PubMed]

- Bach PB. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with CT screening. N Engl J Med 2011;365:2036-author reply 2037-8. [PubMed]

- Strong K, Wald N, Miller A, et al. Current concepts in screening for noncommunicable disease: World Health Organization Consultation Group Report on methodology of noncommunicable disease screening. J Med Screen 2005;12:12-9. [PubMed]

- Humphrey LL, Deffebach M, Pappas M, et al. Screening for lung cancer with low-dose computed tomography: a systematic review to update the U.S. preventive services task force recommendation. Ann Intern Med 2013. [Epub ahead of print]. [PubMed]

- Patel D, Akporobaro A, Chinyanganya N, et al. Attitudes to participation in a lung cancer screening trial: a qualitative study. Thorax 2012;67:418-25. [PubMed]

- van der Aalst CM, van Iersel CA, van Klaveren RJ, et al. Generalisability of the results of the Dutch-Belgian randomised controlled lung cancer CT screening trial (NELSON): does self-selection play a role? Lung Cancer 2012;77:51-7. [PubMed]

- Youlden DR, Cramb SM, Baade PD. The international epidemiology of lung cancer: geographical distribution and secular trends. J Thorac Oncol 2008;3:819-31. [PubMed]

- Marshall H, Bowman R, Crossin J, et al. The Queensland Lung Cancer Screening Study: risk stratification using participant data and lung function tests can significantly increase screening effectiveness, Journal of Thoracic Oncology 4th Australian Lung Cancer Conference (ALCC), Adelaide, 2012.

- Tammemagi CM, Pinsky PF, Caporaso NE, et al. Lung cancer risk prediction: Prostate, Lung, Colorectal And Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial models and validation. J Natl Cancer Inst 2011;103:1058-68. [PubMed]

- Tammemägi MC, Katki HA, Hocking WG, et al. Selection criteria for lung-cancer screening. N Engl J Med 2013;368:728-36. [PubMed]

- Cassidy A, Myles JP, van Tongeren M, et al. The LLP risk model: an individual risk prediction model for lung cancer. Br J Cancer 2008;98:270-6. [PubMed]

- Australian Population Health Development Principal Committee Screening Subcommittee, Population based screening framework. Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, 2008.

- Bianchi F, Nicassio F, Marzi M, et al. A serum circulating miRNA diagnostic test to identify asymptomatic high-risk individuals with early stage lung cancer. EMBO Mol Med 2011;3:495-503. [PubMed]

- Hennessey PT, Sanford T, Choudhary A, et al. Serum microRNA biomarkers for detection of non-small cell lung cancer. PloS One 2012;7:e32307. [PubMed]

- Peled N, Hakim M, Bunn PA Jr, et al. Non-invasive breath analysis of pulmonary nodules. J Thorac Oncol 2012;7:1528-33. [PubMed]

(译者:周支瑞;校对:顾兵)

(本译文仅供学术交流,实际内容请以英文原文为准。)