Chondroblastoma of the rib in a 47-year-old man: a case report with a systematic review of literature

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (1), the chondroblastoma is a relatively benign tumour, characterised by highly cellular and relatively undifferentiated tissue, made up of rounded or polygonal chondroblast-like cells with distinct outlines and multi-nucleated giant cells of osteoclast type arranged singly or in groups. A cartilaginous intercellular matrix with areas of focal calcification is a characteristic of that tumour. The term benign chondroblastoma was suggested by Jaffe and Lichtenstein (2) to describe a rare tumour with a predilection for the epiphyses of long bones. Kolodny (3), in 1927, described the chondroblastoma as a giant cell variant, and Codman (4), in 1931, used the term epiphyseal chondromatous giant cell tumour. Chondroblastoma is a rare benign bone lesion, and it accounts for less than 1% of all bone tumours (5). It usually occurs in adolescent and young adults between 10 and 20 years (5,6); the most common site is proximal tibia, femur, and shoulder (6,7). Numerous studies have shown that it arises from a secondary ossification centre in epiphyseal plates and apophyses, and only rare cases have been reported in the diaphyseal region (8). Only a few case series have been reported; the largest is about 60–70 patients (6,9,10).

Case presentation

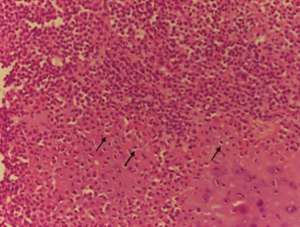

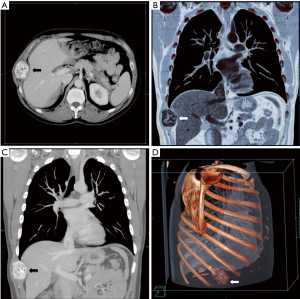

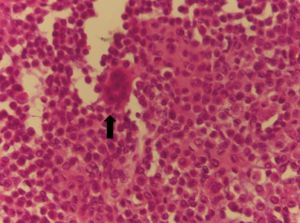

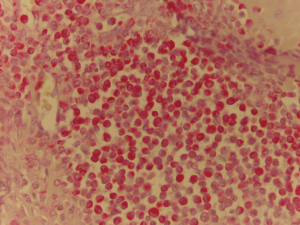

A 47-year-old man, with no previous medical history, was admitted because of a solid, visible thoracic mass and persistent moderate pain in the right hemithorax for 4 months. The lesion has increased over 10 years, with no clinical feature. On physical examination, a fixed palpable mass with pressing pain was noted in the lateral arch of the IX rib. The overlying skin was normal with no sensor deficit. The patient had a history of right chest trauma 20 years ago. A plain radiography showed a well-defined lytic defect, measuring 45 mm of the IX right rib. Computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrates an area of extensive lytic bony destruction, measuring 49 mm × 43 mm × 37 mm, with conserved cortex. The margins were well delineated with some ossifying matrix (Figure 1). There was no evidence of extension to the adjacent soft tissue. A benign osseous lesion, such a chondroma, was suspected. En bloc resection of the anterolateral arch of the IX right rib including 30 mm of the normal cortex and partial diaphragmatic resection were performed. Chest wall and diaphragmatic defect did not require any prosthetic reconstruction. We reconstructed the diaphragmatic defect with interrupted Vicryl 1 adjusting the diaphragm on the VIII rib, to create a tight closure with uniformly distributed tension. Functional outcome of the patients was excellent without pain or paradoxical motion. The final pathologic diagnosis was chondroblastoma; macroscopically it was a round and lucent lesion, measuring 55 mm × 45 mm × 40 mm in size. Microscopically, the tumour was constituted by sheets of mononuclear, polyhedral small cells admixed with giant cells (Figure 2) and zone of lacy calcification (chicken wire calcification) (Figure 3). Immunohistochemistry examination showed reactivity of neoplastic cells for S-100 protein, MNF116 cytokeratin (Figure 4), epithelial membrane antigen and Ki-67 Clone MIB-1 (1.5%). The excellent postoperative course was observed, with no complication and hospital discharge after two days. No recurrence and no lung metastases were found at 4 years follow-up.

Discussion

Chondroblastoma account for approximately 1% to 2% of all bone tumours and most patients are between 10 and 25 years of age at the diagnosis, with a male predominance (5,11,12). In our report, the age was 47 at the diagnosis, a very uncommon age. No risk factors and pathogenesis are known for chondroblastoma. More than 75% of chondroblastoma lesion involves long bones; epiphyseal and epimetaphyseal regions of the distal and proximal femur, proximal homers and proximal tibia are the most common sites (6,13). Other locations are acetabulum, ilium, talus, calcaneus, patella, and temporal bone (14,15). Typically, chondroblastoma affects a single bone, but it can involve two distinct anatomic sites (16), and pain is the most common symptom, usually present for less than 1 year (6,7,17). Soft tissue swelling, mass, or joint effusion is present in about 20% of cases. Chondroblastoma is usually well-circumscribed, round or oval lesion (3) on the radiograph. CT scan can show matrix mineralization, cortical erosion and soft tissue extension. The aggressiveness of the lesion varies among studies. In larger chondroblastomas, there can be an extension into the metaphysis or cortical destruction with the periosteal new bone formation. Aggressive lesions tend to have a higher recurrence rate (9,12). The histological characteristics finding are the presence of chondroblast and chondromyxoid stroma surrounding neoplastic cell. The specific cells are uniform, round to polygonal with well-defined cytoplasmic borders, with mainly clear cytoplasm. Sometimes a nuclear groove or small nucleoli are present. Randomly distributed osteoclast-type giant cells are almost always present. Variable area of deposition of chondroid material accompanies the chondroblast (6,18). A distinctive microscopic finding is the existence of a zone of lacy calcification: “chicken wire” calcification. A reactivity of neoplastic cell for S-100 protein, vimentin and cytokeratin are most commonly observed in the immunohistochemical pattern. Chondroblastoma should usually be differentiated with giant cell tumour, chondromyxoid fibroma, osteosarcoma, eosinophilic granuloma, clear cell chondrosarcoma and chondroblastoma-like chondroma (19). Both giant cell tumours and chondroblastoma occur at the end of the bone. But at RX examination chondroblastoma is better demarcated. Moreover, chondroblastoma shows chondroid matrix, calcifications which are not a feature for a giant cell tumour. Chondromyxoid fibroma involves the epiphysis, have lobulated growth pattern with a myxoid background. A rare type of osteosarcoma cytological features is similar to chondroblastoma; however, in this kind of osteosarcoma the cells are arranged in a sheet-like pattern and permeate bony trabeculae (20-22). There is no accepted standard treatment for chondroblastoma. Earlier reports advocated “curettage” for the removal of these lesions, en bloc resection while following contemporary articles take a more aggressive approach, like wide local excision. Curettage alone, or with associated cryosurgery is described (23,24). Radiotherapy has also been used but has substantially no current role, like chemotherapy. Local recurrence is the most frequent complication (14–18%) (4), particularly with subtotal resection. Metastasis, when it occurs, most frequently involves the lung and tends to occur at the time of primary tumour recurrence and may develop along the malignant bony lesion. Pulmonary metastases are clinically non-progressive and can often be treated by limited surgical resection or simple observation. Recurrence may be treated with curettage and with marginal excision of the soft tissue component. Malignant transformation is rare; pulmonary metastases may develop along with the malignant bone lesion (25) and can often be treated by surgical resection or follow-up (26). Prognosis of these lesions is excellent, 90% successfully treated by curettage or en bloc resection. There are no international guidelines for an appropriate and cost-effective follow-up. Our follow-up included a physical examination and chest radiography every 3 months, and chest CT scan, bronchoscopy, abdominal ultrasound, brain CT scan and bone scan every 6 months for 3 years, then every year over the following 5 years. An extensive follow-up, with acceptable cost, may improve the outcome of patients through detection of asymptomatic recurrences; however, validation by prospective studies is required.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the peculiarity of this case is the long-time rib growth of a chondroblastoma in a middle age man.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this manuscript and any accompanying images.

References

- Fletcher CDM, Unni KK, Mertens F. Pathology and genetics of tumours of soft tissue and bone. Oxford: IARC Press, 2002.

- Jaffe HL, Lichtenstein L. Benign chondroblastoma of bone: a reinterpretation of the so-called calcifying or chondromatous giant cell tumour. Am J Pathol 1942;18:969-91. [PubMed]

- Kolodny A. Bone sarcoma: the primary malignant tumours of bone and the giant-cell tumour. Surg Gynae Obstet 1927;44.

- Codman EA. Epiphyseal chondromatous giant cell tumours of the upper end of the humerus. Surg Gynae Obstet 1931;52:543-8.

- Campanacci M. Bone and soft tissue tumours: clinical features, imaging, pathology and treatment. 2 ed. Vienna: Springer-Verlag, 1999.

- Turcotte RE, Kurt AM, Sim FH, et al. Chondroblastoma. Hum Pathol 1993;24:944-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huvos AG, Marcove RC, Erlandson RA, et al. Chondroblastoma of bone. A clinicopathologic and electron microscopic study. Cancer 1972;29:760-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Clapper AT, DeYoung BR. Chondroblastoma of the femoral diaphysis: report of a rare phenomenon and review of literature. Hum Pathol 2007;38:803-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Masui F, Ushigome S, Kamitani K, et al. Chondroblastoma: a study of 11 cases. Eur J Surg Oncol 2002;28:869-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schajowicz F, Gallardo H. Epiphysial chondroblastoma of bone. A clinico-pathological study of sixty-nine cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1970;52:205-26. [PubMed]

- Bulanov DV, Semenova LA, Makhson AN, et al. Chondrosarcoma of the larynx. Arkh Patol 2007;69:50-2. [PubMed]

- Suneja R, Grimer RJ, Belthur M, et al. Chondroblastoma of bone: long-term results and functional outcome after intralesional curettage. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2005;87:974-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Long KL, Absher KJ, Draus JM Jr. Chondromyxoid fibroma of the second rib. J Pediatr Surg 2013;48:1442-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ghekiere J, Geusens E, Lateur L, et al. Chondroblastoma of the patella with a secondary aneurysmal bone cyst. Eur Radiol 1998;8:992-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bertoni F, Unni KK, Beabout JW, et al. Chondroblastoma of the skull and facial bones. Am J Clin Pathol 1987;88:1-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Roberts PF, Taylor JG. Multifocal benign chondroblastomas: report of a case. Hum Pathol 1980;11:296-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hsu CC, Wang JW, Chen CE, et al. Results of curettage and high-speed burring for chondroblastoma of the bone. Chang Gung Med J 2003;26:761-7. [PubMed]

- Granados R, Martín-Hita A, Rodríguez-Barbero JM, et al. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of chondroblastoma of soft parts: case report and differential diagnosis with other soft tissue tumors. Diagn Cytopathol 2003;28:76-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bousdras K, O'Donnell P, Vujovic S, et al. Chondroblastomas but not chondromyxoid fibromas express cytokeratins: an unusual presentation of a chondroblastoma in the metaphyseal cortex of the tibia. Histopathology 2007;51:414-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reid LB, Wong DS, Lyons B. Chondroblastoma of the temporal bone: a case series, review, and suggested management strategy. Skull Base Rep 2011;1:71-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ayadi-Kaddour A, Mlika M, Chaabouni S, et al. Mesenchymal hamartoma of the chest wall in an infant. Pathologica 2007;99:440-2. [PubMed]

- Yang J, Tian W, Zhu X. Chondroblastoma in the long bone diaphysis: a report of two cases with literature review. Chin J Cancer 2012;31:257-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ramappa AJ, Lee FY, Tang P, et al. Chondroblastoma of bone. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2000;82-A:1140-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schreuder HW, Pruszczynski M, Veth RP, et al. Treatment of benign and low-grade malignant intramedullary chondroid tumours with curettage and cryosurgery. Eur J Surg Oncol 1998;24:120-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ostrowski ML, Johnson ME, Truong LD, et al. Malignant chondroblastoma presenting as a recurrent pelvic tumor with DNA aneuploidy and p53 mutation as supportive evidence of malignancy. Skeletal Radiol 1999;28:644-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rodgers WB, Mankin HJ. Metastatic malignant chondroblastoma. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 1996;25:846-9. [PubMed]