Urokinase application for hemothorax in pulmonary mucormycosis

Introduction

Pulmonary mucormycosis is an uncommon but often lethal opportunistic infection. The occurrence of a hemothorax and the consecutive need of repetitive surgical interventions even increases the morbidity.

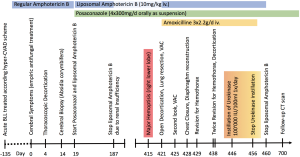

We present a case of pulmonary mucormycosis in an 18-year-old woman with acute B-lymphoblastic leukemia. Despite long-term use of antifungal treatment, the infection persisted and could only be treated by surgery (Figure 1).

Case presentation

An 18-year-old patient initially presented to her general practitioner with neck pain, nausea, fever, coughing and pain in the limbs. Her blood test showed signs of a lymphatic leukemia (leukocytosis with 68% blasts, thrombocytopenia of 106 g/L, anemia of 83 g/L), therefore she was admitted for elective workup to our hospital.

She presented with hypotony, tachycardia but without fever. She had cervical, inguinal, axillary and retroauricular lymphadenopathy and a palpable spleen. The cause was confirmed as an acute B-lymphoblastic CD20 negative, BCR-ABL1 negative leukemia (B-ALL). Treatment was started according to hyper-CVAD (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, adriamycin and dexamethasone) scheme but could not be completed due to a cerebrovascular insult with left side hemiparesis which was caused by a septic embolism in the context of generalized mucormycosis diagnosed by cerebral biopsy and pleural tissue. In the cerebral biopsy broad spectrum fungal PCR has been positive for Absidia corymbifera. Later in the sputum Rhizopus species could be detected by culture sequencing. Histopathological examination of the pleural tissue showed fungal hyphae in the initial thoracoscopy and vascular invasive fungal hyphae in the cerebral biopsy in concordance with Mucorales species. The proven invasive mucormycosis (1) was treated with dual antifungal therapy (liposomal amphotericin B, 10 mg/kg with treatment breaks resp. dose reduction due to renal insufficiency and posaconazole, 4×300 mg/d orally as suspension). Three months later MRI confirmed a regression of the cerebral mucor which allowed to reduce the treatment to posaconazole only (serum levels of posaconazole have been checked regularly as adequate). Both the B-ALL and the mucormycosis continued to be in remission.

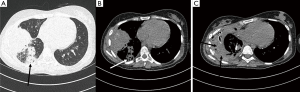

More than a year later the patient admitted herself to the emergency room because of severe hemoptysis. CT scan revealed a bleeding spot in the right lower lobe with signs of mycotic infection (Figure 2A,B). During that time posaconazole level has been adequate with 2.5 mg/mL.

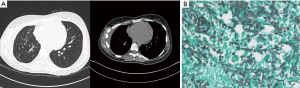

We performed an open decortication with partial non-anatomical resection of the lower and middle lobe of the right lung. To remove all the infected tissue a small part of the infiltrated diaphragm also had to be removed. Additionally, a vacuum (VAC)-sponge was placed in the thorax. The histological check-up confirmed the diagnosis of invasive mucormycosis by detection of fungal hyphae under direct macroscopy.

Postoperatively the patient presented in good condition, even though the chest X-ray showed a partial atelectasis in the right lower lobe, the remaining lung was adequately expanded. Antifungal therapy with posaconazole and amphotericin B was continued.

Five days later, a planned second look was performed with an additional change of the VAC-sponge. Eight days after the initial operation the sponge was changed again and a Goretex patch 10 cm × 8 cm for partial replacement of the diaphragm has been placed and the chest has been definitively closed.

Over the course of a week the X-rays showed progressive worsening, which led to the suspicion of a recurring hemothorax (Figure 2C). An emergency thoracotomy and two more open revisions were needed. Thereafter, the patient finally stabilized and was moved from intensive care unit to the ward.

Eight days later, to address the ongoing hemothorax problem we instilled urokinase (100,000 IU/100 mL) into the right thoracic cavity once daily for 10 days. Lung function and radiologic controls showed a steady improve with reduced infiltration and effusion.

Follow-up

A brain MRI showed a partial remission of the mucormycosis and no new brain lesions. The patient’s left side hemiparesis continued to improve with ongoing physiotherapy. Forty-seven days after the initial hospitalization the patient was discharged into rehabilitation.

Ten months after the pulmonary resection, the patient showed improvements in both lab parameters (normal, microscopic blood test, normal cell lysis parameters and minimal residual disease markers not detectable by PCR) and clinical presentation (Figure 3). She is in remission in leukemia and controlled mucormycosis under continuous posaconazole treatment.

Discussion

Among pulmonary mycoses aspergillosis, candidiasis and cryptococcosis are the most frequent types, whereas pulmonary infections with mucorales (2). Mucormycosis is an increasing dangerous and life-threatening disease caused by fungi of the order mucorales with a high mortality of around 50% (3). While in immunocompetent patients, phagocytes kill the mucorales by generating oxidative metabolites and cationic peptides defensins, immunocompromised patients are much more at risk (4).

One of the defining characteristics of invasive fungal infection in mucormycosis is vascular invasion, which can lead to thrombosis and necrosis. The fungus is likely to spread and is difficult to control surgically. In combination with aggressive treatment with antifungal agents, surgical resection of infected tissue up to anatomical resections can be performed safely even in haematological patients, however with a perioperative mortality of 5–10% (5). Important is the control of the underlying haematologic disease.

Though not as common as other opportunistic fungal infections such as aspergillosis or candidiasis, it continues to be a problem in immunocompromised patients.

The mortality rate for mucormycosis infections ranges from 40% to over 90% in patients with stem cell transplantation and dissemination, despite of state of the art medical care (6,7).

Early diagnosis of the fungus is the key of successful treatment. If possible, the underlying disease should be cured. Treatment for mucormycosis is a combination of antifungal medication, as in this case of neurological involvement high dose of liposomal amphotericin B and posaconazole for maintenance therapy (3) and if possible surgical debridement of the infected tissue.

If present in the chest cavity it can lead to recurring hemothorax.

To fight the potentially serious hemothorax in intensive care medicine the usual approach is to either perform a thoracotomy or video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) to drain the residual blood. In recent years, the use of a tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) such as urokinase, which liquefies the clotted hemothorax, has come up as a less invasive method for treatment (8). Fibrinolytic agents as streptokinase or urokinase have been used safely in the posttraumatic hemothorax setting (9) or after lung resections (10). The risk of relevant bleeding using these agents is described in the literature with 2–15% in mostly immunocompetent patients.

In our PubMed search, we could not find an example of a patient with mucormycosis who has been treated with urokinase. Due to the comorbidity in mucormycosis patients the risk of repeated surgery is relatively high.

Our case shows the successful treatment of an immunocompromised patient with generalized mucormycosis using the combination of surgical removal of the infected tissue and antifungals. To minimize the need for repetitive surgery in recurrent hemothorax the use of urokinase is a treatment option.

It is of high importance to treat those patients in a multidisciplinary experienced center. Especially using a fibrinolytic agent in a situation like this requires a careful and tight monitoring of the patient course.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this manuscript and any accompanying images.

References

- De Pauw B, Walsh TJ, Donnelly JP, et al. Revised definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. Clin Infect Dis 2008;46:1813-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang X, Wang R, Di X, et al. Different microbiological and clinical aspects of lower respiratory tract infections between China and European/American countries. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:134-42. [PubMed]

- Danion F, Aguilar C, Catherinot E, et al. Mucormycosis: New Developments into a Persistently Devastating Infection. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2015;36:692-705. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Spellberg B, Edwards J Jr, Ibrahim A. Novel perspectives on mucormycosis: pathophysiology, presentation, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev 2005;18:556-69. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chretien ML, Legouge C, Pagès PB, et al. Emergency and elective pulmonary surgical resection in haematological patients with invasive fungal infections: a report of 50 cases in a single centre. Clin Microbiol Infect 2016;22:782-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Spellberg B, Walsh TJ, Kontoyiannis DP, et al. Recent advances in the management of mucormycosis: from bench to bedside. Clin Infect Dis 2009;48:1743-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Roden MM, Zaoutis TE, Buchanan WL, et al. Epidemiology and outcome of zygomycosis: a review of 929 reported cases. Clin Infect Dis 2005;41:634-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stiles PJ, Drake RM, Helmer SD, et al. Evaluation of chest tube administration of tissue plasminogen activator to treat retained hemothorax. Am J Surg 2014;207:960-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Inci I, Ozçelik C, Ulkü R, et al. Intrapleural fibrinolytic treatment of traumatic clotted hemothorax. Chest 1998;114:160-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huang D, Zhao D, Zhou Y, et al. Intrapleural Fibrinolytic Therapy for Residual Coagulated Hemothorax After Lung Surgery. World J Surg 2016;40:1121-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]