A suspected case of inflammatory bronchial polyp induced by bronchial thermoplasty but resolved spontaneously

Introduction

Bronchial thermoplasty (BT) is a novel treatment for patients with severe asthma (1). Although respiratory adverse events such as asthma attack, atelectasis, and pneumonia are widely known as complications following BT (1), endobronchial organic lesions such as inflammatory bronchial polyps are not generally recognized as such by clinicians. We experienced a suspected case of an inflammatory bronchial polyp induced by BT that showed a spontaneous resolution. Written patient consent was obtained for this case report.

Case presentation

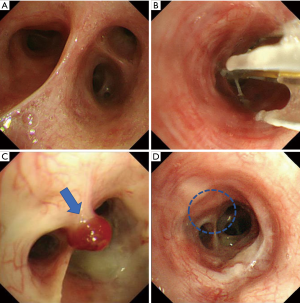

A 30-year-old man with severe refractory asthma was referred to our hospital to receive BT. The patient was diagnosed as asthma at 25 years old; the patient had no medical history otherwise. The patient’s medications included high-dose fluticasone propionate/formoterol combination inhaler (1,000 µg/36 µg daily), tiotropium bromide inhaler (5 µg daily), ciclesonide inhaler (400 µg daily), oral prednisolone (10 mg daily), pranlukast (450 mg daily), theophylline (400 mg daily), carbocisteine, hydroxyzine (1,500 mg daily), and ozagrel hydrochloride hydrate (400 mg daily). The patient quit smoking 7 years ago. Expiratory wheezes were heard on chest auscultation. A chest radiograph showed no abnormality. The serum total IgE level was 44.6 IU/mL without any sensitization to specific aeroallergens. Inflammatory markers showed low blood eosinophil counts (8/µL) but an elevated fraction of exhaled nitric oxide (33.9 ppb). Forced expiratory volume in one second was 3.48 L (91.3% of predicted). Omalizumab and mepolizumab were not applicable to this non-atopic patient without blood eosinophilia. Thus, BT was considered the optimal option for this patient. BT initially for the right lower lobe was uneventful without serious complications. The total number of cauterization to the right B6b was seven (each once to 6b, 6bi, 6biα, 6biβ, 6bii, 6biiα and 6biiβ), which was intact before and during the first BT (Figure 1A,B). The second BT was performed at 6 weeks after first BT, which was delayed due to a patient’s circumstance. There were no endoscopic abnormalities again during the procedure. However, when the final BT was conducted at 3 weeks after the second BT procedure (i.e., 9 weeks after the first BT), bronchoscopy revealed a dark red pedunculated polyp at the right B6b which was treated by the first BT (Figure 1B,C). A classical inflammatory bronchial polyp was suspected visually, but transbronchial biopsy was not conducted due to the risk of hemorrhage. At 23 weeks after the first BT, bronchoscopy revealed a spontaneous disappearance of the polyp from that region (Figure 1D).

Discussion

The long-term therapeutic benefits and safety of BT have been known for at least 5 years (1). A number of transient adverse events, such as asthma attack, hemoptysis, and pneumonia, are sometimes observed after BT. However, endobronchial lesions including inflammatory bronchial polyps have not been reported. Recently, it has been reported that chest computed tomography after BT had revealed peribronchial consolidations and ground-glass opacities without clinical symptoms, which spontaneously eliminated or disappeared within 1 month (2). Histological analysis performed 5 to 20 days after BT showed metaplasia of the mucus ducts and glands, thrombosis in the perichondrial vessels, mild focal necrotic cartilage, and peribronchial pneumonitis characterized by a patchy accumulation of inflammatory cells, mainly lymphocytes in interstitial spaces, and fibroblasts (3). A similar phenomenon was found after radiofrequency ablation of pulmonary neoplasms which also involves moderately high temperature (>60 °C), causing tissue inflammation with edema, infiltration of inflammatory cells, and functioning blood vessels (4). These thermal-induced histological changes may be associated with the development of polyp after the BT procedure. Indeed, we observed the polypoid lesion in right B6b, the location of which was consistent with the attachment of the catheter during the first BT (Figure 1B).

Among the central airway tumors, inflammatory bronchial polyps are rare and their frequency remains unknown (5). We should distinguish endobronchial tumors such as primary lung cancer (e.g., squamous cell carcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma and carcinoid tumors), metastatic cancer (e.g., renal cell carcinoma and colon carcinoma), and benign tumors (e.g., hamartoma, leiomyoma, chondroma, lipoma and inflammatory bronchial polyps, etc.). Although histological evaluation is essential for these diagnoses, specific external appearance can be observed by endoscope. For example, squamous cell carcinoma has vascular hyperplasia, necrosis, and irregularities on the mucosal membrane. Adenoid cystic carcinoma is a rough tumor with vascular hyperplasia, and carcinoid tumor is typically a hemispherical, smooth and red tumor (6). The characteristic findings of metastatic endobronchial tumors vary with the primary lesions (e.g., endobronchial metastasis from renal cell carcinoma bleeds easily). These differential diagnoses are unlikely in our case. Additionally they almost never disappear spontaneously. For the benign tumors, hamartomas and chondromas are white or yellow, smooth tumors, and hard as they contain cartilage tissue. Leiomyomas emerge from the membranous portion of the bronchus and they are covered with normal bronchial mucosa. Lipomas are smooth polypoid submucosal tumors (7). These characteristics are not consistent with our case. Inflammatory bronchial polyps are white or red lustrous polyps with a smooth, but sometimes rough, mucous membrane without erosion or ulcers (6). Inflammatory bronchial polyps are developed by epithelialization secondary to bronchial mucosa injury with submucosal extension, such as intubation or thermal injury, and damage to the fibrous connective tissue with the infiltration of inflammatory cells (5,8,9). Although pathological findings could not be evaluated in the current case, a classical inflammatory bronchial polyp is the most likely diagnosis because of its appearance and clinical course (10). However, it remains a matter of speculation.

The association of inflammatory bronchial polyps with asthma is very rare. Niimi et al. reported a case of asthma with an inflammatory bronchial polyp that did not change for 6 years but regressed when the patient commenced inhaled corticosteroids (11). In this case, the biopsy specimen showed the infiltration of lymphocytes and eosinophils in the polyp, suggesting that inflammatory bronchial polyps might be attributed to chronic inflammation of asthma (11). In the current case, the inflammatory bronchial polyp newly developed within 9 weeks after the first BT and had already regressed 14 weeks after the final BT. Irritation due to thermoinactivation to bronchial mucosa may have exaggerated the infiltration of inflammatory cells such as neutrophils in the airways, which may have resulted in the development of inflammatory bronchial polyps. However, we could not perform histological evaluation of the polypoid lesion. Therefore, the definite diagnosis of inflammatory bronchial polyp could not be made. Although this is the most considerable limitation of this case report, we think clinicians should take into account the development of an inflammatory bronchial polyps after BT even if it may be a rare complication.

The natural course of inflammatory bronchial polyps remains unknown because the majority of them are removed for symptomatic relief (10). Meanwhile, in a case following endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) reported by Lee et al., the inflammatory bronchial polyp regressed spontaneously without treatment (10). Our patients had no respiratory symptoms caused by the polypoid lesion so we could observe the natural course without its removal, which resulted in spontaneous resolution. Unless causing severe respiratory symptoms, observation without removal may be a reasonable treatment choice.

In conclusion, to our best knowledge, this is the first report of suspected inflammatory bronchial polyp induced by BT. We should consider the possibility of its occurrence, and also its spontaneous resolution.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: A Niimi received lecture fees from Astellas, AstraZeneca, Kyorin, GSK, MSD, and Boehringer Ingelheim. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

References

- Wechsler ME, Laviolette M, Rubin AS, et al. Bronchial thermoplasty: Long-term safety and effectiveness in patients with severe persistent asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013;132:1295-302. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Debray MP, Dombret MC, Pretolani M, et al. Early computed tomography modifications following bronchial thermoplasty in patients with severe asthma. Eur Respir J 2017.49. [PubMed]

- Miller JD, Cox G, Vincic L, et al. A prospective feasibility study of bronchial thermoplasty in the human airway. Chest 2005;127:1999-2006. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abtin FG, Eradat J, Gutierrez AJ, et al. Radiofrequency ablation of lung tumors: imaging features of the postablation zone. Radiographics 2012;32:947-69. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gamblin TC, Farmer LA, Dean RJ, et al. Tracheal polyp. Ann Thorac Surg 2002;73:1286-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi E, Nagai T, Kamishima K, et al. Inflammatory polyp of the respiratory tract -with special reference to fifty-one idiopathic cases. J Jpn Soc Respir Endoscopy 1984;6:163-71.

- Niimi A, Kobayashi H, Sugita T, et al. A case of endobronchial hamartoma completely removed by transbronchial biopsy. J Jpn Soc Respir Endoscopy 1990;12:190-4.

- McShane D, Nicholson AG, Goldstraw P, et al. Inflammatory endobronchial polyps in childhood: clinical spectrum and possible link to mechanical ventilation. Pediatr Pulmonol 2002;34:79-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Adams C, Moisan T, Chandrasekhar AJ, et al. Endobronchial polyposis secondary to thermal inhalational injury. Chest 1979;75:643-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee KM, Jang SM, Oh SY, et al. The Natural Course of Endobronchial Inflammatory Polyps as a Complication after Endobronchial Ultrasound-Guided Transbronchial Needle Aspiration. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul) 2015;78:419-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Niimi A, Amitani R, Ikeda T, et al. Inflammatory bronchial polyps associated with asthma: resolution with inhaled corticosteroid. Eur Respir J 1995;8:1237-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]