Relationship between performance status or younger age and osimertinib therapy in T790M-positive NSCLC: are the available data convincing?

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) represents the leading cause of death for cancer (1). In 2004, for the first time Lynch et al. demonstrated that a subgroup of NSCLC patients (10–15%), harboring somatic mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene, showed sensitivity and clinical benefit to a novel class of drugs targeting the tyrosine kinase domain; the so called tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) (2). After five years, Mok et al. showed, in the phase III IPASS trial, the superiority of the first generation TKI gefitinib in comparison with a standard-of-care regimen (carboplatin-paclitaxel) in patients carrying the EGFR mutation (3). The 12-month rates of progression-free survival (PFS) were 24.9% with gefitinib respect to 6.7% treated with chemotherapy with the evidence of a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.48 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.36–0.64; P<0.001) (3). Similar results were obtained by Rosell et al. in the European EURTAC study, in which erlotinib (first generation TKI) showed its superiority respect to standard chemotherapy (median PFS was 9.7 versus 5.2 months, respectively; HR 0.37, 95% CI: 0.25–0.54; P<0.0001) (4). Differently from the first generation, the second generation TKIs (afatinib and dacomitinib) irreversibly bind the EGFR. In the LUX-Lung studies 3 and 6, the efficacy of afatinib was analyzed respect to standard chemotherapy. In these studies, either Asiatic and non-Asiatic patients showed an improvement in PFS versus chemotherapy. In the LUX-Lung 3 the median PFS was 11.1 versus 6.9 months, respectively (HR 0.58, 95% CI: 0.43–0.78; P=0.001), while in the LUX-Lung 6 median PFS was 11.0 versus 5.6 months, respectively (HR 0.28, 95% CI: 0.20–0.39; P<0.0001) (5,6). In the ARCHER 1050, dacomitinib was compared with gefitinib showing an increase in PFS in the dacomitinib versus the gefitinib group (14.7 versus 9.2 months, respectively; HR 0.59, 95% CI: 0.47–0.74; P<0.0001) (7). Moreover, median overall survival (OS) was significantly longer with dacomitinib than with gefitinib being 34.1 versus 26.8 months (HR 0.76, 95% CI: 0.582–0.993; P=0.0438) (8). In nearly 50% of cases, the acquired resistance to first- or second-generation TKIs was represented by the onset of a new EGFR mutation, the exon 20 T790M. To overcome this resistance, osimertinib, a third generation TKI, was developed. In the AURA3, Mok et al. demonstrated the superiority of osimertinib versus pemetrexed plus carboplatin or cisplatin in NSCLC patients harboring EGFR exon 20 T790M both in patients without (median PFS 10.1 versus 4.4 months; HR 0.30, 95% CI: 0.23–0.41; P<0.001) and with central nervous system (CNS) metastasis (median PFS 8.5 versus 4.2 months; HR 0.32, 95% CI: 0.21–0.49) (9). The FLAURA phase III trial randomized untreated EGFR mutated advanced NSCLC patients to receive osimertinib or gefitinib/erlotinib. The median PFS was 18.9 months in the osimertinib arm versus 10.2 months in the gefitinib/erlotinib arm (HR 0.46, 95% CI: 0.37–0.57; P<0.001) (10).

In the Journal of Thoracic Disease, Kato et al. (11) report a retrospective analysis of 31 patients with T790M-positive NSCLC and acquired resistance to initial EGFR-TKIs who received osimertinib therapy. As reported by the Authors, the identification of T790M-positive NSCLC patients in this study was carried out by using the SCORPION ARMS probes in Real-Time PCR. Despite this approach is considered a well-established method to analyse DNA derived from tissue samples, its sensitivity is still limited to better define the real T790M positive population on circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA). Today, other approaches, such as digital PCR or specific adapted ultra—deep Next Generation Sequencing panels are preferred for liquid biopsy setting (12-14).

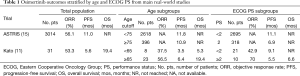

Several clinical features were associated with patients’ age and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) as potential confounding factors. Most of the retrieved patients (74%) were aged ≥65 years and ECOG PS was 2–4 in 32% of them. In this patients’ series, ECOG-PS and age were the only clinical features associated significantly with the prognosis of patients on osimertinib therapy at univariate analysis for PFS, with a median of 3.5 months in young patients and 6.4 months in the elderly (HR 2.41; P=0.041). Median OS was 5.3 and 19.4 months, respectively (HR 2.58; P=0.067). The PFS in patients with good ECOG-PS was 9.1 versus 5.5 months reported in those with poor ECOG-PS (HR 0.39; P=0.071) while OS was not reached versus 6.6 months, respectively (HR 0.39; P=0.061). The objective response rate (ORR) was 53.3% in all patients. A trend towards higher ORR was reported in favor of elderly versus younger patients (56.5% versus 37.5%; P=0.43) and those with poor versus better ECOG-PS (70% versus 42.9%; P=0.25). At the multivariate analysis, both age and ECOG-PS were independent predictors of osimertinib treatment efficacy (11) (Table 1).

Full table

The age cutoff to define the elderly population is still debated. The age of 65 years is usually considered as a cut-point to select elderly population from the epiemiologists’ standpoint. In fact, many trials used 65 years as the reference point for the age subgroup analysis. Conversely, in clinical trials prospectively addressed to examine treatment efficacy in elderly patients, 70 years is considered the age commonly used as lower limit for patient selection because the incidence of age-related changes starts to increase at that age (16). Therefore, it is difficult to compare the results coming from retrospective analyses with those from prospective trials performed in elderly patients. The activity of osimertinib reported by the retrospective analysis of the study by Kato et al. (11) was lower in younger than in elderly patients. The results from the AURA3 trial, in which the range of age for osimertinib was 25–85 years, showed that the benefit of osimertinib was maintained among all age subgroups (cutoff age of 65 years) (9). The activity of osimertinib was the same regardless of the cutoff age of 65 years also as first-line treatment as reported in the FLAURA trial in which the range of age of patients enrolled was 26–85 (10). Furthermore, it is important to underline that, in these trials (9,10), almost all patients carried common EGFR mutations, deletions of exon 19 or point mutation of exon 21 (L858R), like those enrolled in the study by Kato et al. (11). The largest, international, real-world treatment study of osimertinib in EGFR T790M-positive NSCLC (ASTRIS study), enrolled 3,014 patients (69% were Asian) and provided also outcomes in predefined patient subpopulations of interest such as elderly (age cutoff ≥75 years) and those with ECOG PS 2. The preliminary results showed a median PFS of 11.0 months, which was similar regardless of patients’ age (range of age: 27–92), with younger patients (<75 years; n=2,618) showing a median PFS of 10.9 months and elderly ones (≥75 years; n=396) of 11.8 months (15) (Table 1). Overall, controversial data speculating on a differential activity and efficacy of EGFR-TKIs according to age in EGFR-mutant NSCLC patients were reported, although clear mechanisms or rationale responsible for this effect have not been showed. Thus, no clear conclusion can be drawn in absence of specific prospective trials.

Performance status represents the most important predictor of outcome in advanced NSCLC. Patients with a PS of 2 tend to tolerate treatment poorly and have a significantly inferior OS compared with those with a PS of 0 to 1. For this reason, PS 2 patients have been historically excluded from clinical trials (17). In the study by Kato et al. (10), 32% of analyzed patients were PS 2–4 showing median PFS and OS of 5.5 and 6.6 months, respectively. In the ASTRIS trial, 318 patients were PS 2 and showed a median PFS of 6.9 months respect to 11.1 months showed by 2,695 patients with PS 0–1 (15) (Table 1). The role of PS 2 as a negative prognostic factor is true regardless the molecular characteristics of advanced NSCLC. However, it is important to underline that patients addressed to receive a targeted agent on the basis of a genomic abnormality (i.e., in oncogene-addicted disease), do benefit from treatment regardless of PS, while such effect is not reproducible for patients with poor PS (for example PS 3–4) selected to receive chemotherapy (i.e., non oncogene-addicted disease). Therefore, this lower efficacy of osimertinib in PS 2–4 NSCLC patients is not related to the drug but it is an effect of this subgroup of patients.

Kato et al. concluded that poor ECOG-PS and younger age were associated with lower efficacy of osimertinib in T790M-positive NSCLC (11). However looking to other studies, many other factors were identified as negative predictors of efficacy by EGFR-TKIs in EGFR-mutated NSCLC (18-20). For this reason, all the available data must be considered just as speculative information and no therapeutic choice can be driven upon this basis. At the same way, the lower activity and efficacy of osimertinib in younger and ECOG PS 2 patients as shown by the study from Kato et al. cannot be considered as a definite and robust evidence.

The very small number of analyzed patients and the retrospective nature represent the main limits of the present study. Nevertheless, such kind of analyses may help in generating hypotheses to be potentially proven in the context of larger trials or patient series more similar to real-world contexts, such as phase IIIB studies or expanded-access-series. In this regard, the final results of the ASTRIS trial would add more robust evidence for clinical practice to the potential factors influencing negatively the efficacy of osimertinib. Moreover, only prospective well-designed trials can really provide information that can influence clinical practice choices.

Acknowledgments

Funding: E. Bria is supported by the Italian Association for Cancer Research AIRC-IG 20583; E Bria was supported by the International Association for Lung Cancer (IASLC), the LILT (Lega Italiana per la Lotta contro i Tumori) and Fondazione Cariverona.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: Umberto Malapelle: Advisory Board member and honoraria as speaker bureau for MSD, Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca; Antonio Rossi: Advisory Board member and honoraria as speaker bureau for MSD, Eli-Lilly, Roche, Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca; Emilio Bria: Speakers’ and travels’ fee from MSD, Astra-Zeneca, Celgene, Pfizer, Helsinn, Eli-Lilly, BMS, Novartis and Roche. Consultant’s fee from and Advisory Board member for Astra-Zeneca, Roche, Pfizer. Institutional research grants from Astra-Zeneca, Roche.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

References

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin 2019;69:7-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med 2004;350:2129-39. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med 2009;361:947-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rosell R, Carcereny E, Gervais R, et al. Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as first-line treatment for European patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (EURTAC): a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:239-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sequist LV, Yang JC, Yamamoto N, et al. Phase III study of afatinib or cisplatin plus pemetrexed in patients with metastatic lung adenocarcinoma with EGFR mutations. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:3327-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu YL, Zhou C, Hu CP, et al. Afatinib versus cisplatin plus gemcitabine for first-line treatment of Asian patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring EGFR mutations (LUX-Lung 6): an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:213-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu YL, Cheng Y, Zhou X, et al. Dacomitinib versus gefitinib as first-line treatment for patients with EGFR-mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (ARCHER 1050): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:1454-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mok TS, Cheng Y, Zhou X, et al. Improvement in overall survival in a randomized study that compared dacomitinib with gefitinib in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer and EGFR-activating mutations. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:2244-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mok TS, Wu Y-L, Ahn M-J, et al. Osimertinib or platinum-pemetrexed in EGFR T790M-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2017;376:629-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Soria JC, Ohe Y, Vansteenkiste J, et al. Osimertinib in untreated EGFR-mutated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2018;378:113-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kato Y, Hosomi Y, Watanabe K, et al. Impact of clinical features on the efficacy of osimertinib therapy in patients with T790M-positive non-small cell lung cancer and acquired resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors. J Thorac Dis 2019;11:2350-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Malapelle U, Raez LE, Serrano MJ, et al. Detection of epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in circulating tumor DNA: reviewing BENEFIT clinical trial. J Thorac Dis 2018;10:6388-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pisapia P, Malapelle U, Troncone G. Liquid biopsy and lung cancer. Acta Cytol 2018;19:1-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Malapelle U, Mayo de-Las-Casas C, Rocco D, et al. Development of a gene panel for next-generation sequencing of clinically relevant mutations in cell-free DNA from cancer patients. Br J Cancer 2017;116:802-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu YL, Cho BC, Zhou Q, et al. ASTRIS: A real world treatment study of osimertinib in patients with EGFR T790M mutation-positive NSCLC. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:abstr 9036.

- Balducci L. Geriatric oncology: challenges for the new century. Eur J Cancer 2000;36:1741-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lilenbaum RC. Treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer in special populations. Oncology (Williston Park) 2004;18:1321-5; discussion 1326, 1329-33.

- Yao ZH, Liao WY, Ho CC, et al. Real-world data on prognostic factors for overall survival in EGFR mutation positive advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with first-line gefitinib. Oncologist 2017;22:1075-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jain A, Lim C, Gan EM, et al. Impact of smoking and brain metastasis on outcomes of advanced EGFR mutation lung adenocarcinoma patients treated with first line epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors. PLoS One 2015;10:e0123587. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim MH, Kim HR, Cho BC, et al. Impact of cigarette smoking on response to epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-tyrosine kinase inhibitors in lung adenocarcinoma with activating EGFR mutations. Lung Cancer 2014;84:196-202. [Crossref] [PubMed]