Women in thoracic surgery: social media and the value of mentorship

Background

For the first time in 2017, the proportion of matriculating female medical students surpassed that of their male colleagues in the United States (1). However, despite these demographic shifts in the overall population of rising physicians, the proportion of practicing female physicians in the workforce still lags significantly behind that of males, particularly within surgical fields (2,3). This finding is in stark contrast to that observed within other specialties, such as pediatrics and obstetrics/gynecology, which attract significantly greater proportions of females, harboring a predominantly female workforce (4). Importantly, it has been established that females are no less successful in completing surgical training or entering the surgical workforce when compared to their male residency colleagues (5). While it will take decades for the population of practicing physicians to reflect this newly achieved equilibrium of sexes in training, it remains concerning that surgical fields are failing to proportionately garner interest from highly qualified, talented female trainees.

This discrepancy is exceedingly apparent in the field of cardiothoracic surgery, with an extremely low percentage of practicing female physicians, far less than other surgical specialties, aside from orthopedic surgery (6). Despite a genuine welcoming from the current community of (largely male) cardiothoracic surgeons, as well as patients and families, the integration of women into the field of cardiothoracic surgery has been sluggish (7). However, organizations such as Women in Thoracic Surgery continue to promote the importance of female surgeons in the field, with international support and myriad opportunities for professional growth and development (8,9).

Nonetheless, factors contributing to the continued underrepresentation of women in this and other male-dominated surgical subspecialties are numerous and complex (10). When considering surgical training, fears regarding sex-based discrimination are cited (11,12). Additionally, perceptions of environments which do not foster family planning and childbearing abound (13). Lastly, several investigations have identified the lack of exposure of female trainees to available female surgical mentors as a limiting factor preventing more women from entering the field (10,12,14). These issues, unfortunately, result in a self-perpetuating prophecy, wherein females do not opt for careers in cardiothoracic surgery because they do not find available role models.

Women are furthermore notably absent from leadership roles locally and at the national level. Women infrequently serve as departmental chairs or division chiefs, and leadership within regional and national organizations additionally lack adequate representation (15-18). In academics, a lesser proportion of women achieve full professorship compared to men, and principal investigators of research endeavors are less likely to be women, though promising trends have been noted (8,19).

In discussing the importance of mentorship, it is often stated that, “You can’t be what you can’t see.” Understandably, the value of mentorship, particularly same-sex mentorship for female trainees, has been increasingly appreciated (10,20,21). Though women seek these relationships in their early career developments, they often find it challenging to identify such mentors (22). Lacking minimal opportunities for mentorship locally, trainees and mentors alike have turned to novel avenues via social media to foster such relationship in the trajectory of professional development (23).

Social media for surgeons

Social media encompasses a variety of online tools and communities, which augment learning, information sharing, and collaboration via expanded networks of novices and experts (24). In-person groups that were formerly small or challenging to identify are now readily accessible. Likewise, otherwise elusive expert opinions and research can be found nearly instantaneously in well-organized fora and communities. The routine, if not ubiquitous, use of smartphones has further promoted the quick and easy use of a variety of social media platforms available through mobile technology.

Increasingly, the value of social media for professional development has been recognized across all professions, although physicians and particularly surgeons have been a bit slower to adopt, citing concerns about patient privacy and the informality of one’s virtual, versus in-person, presence (25,26). However, the value of these online tools continues to be touted across a variety of medical fields, providing opportunities for networking and learning for established experts, trainees, and patients alike. To this end, social media has “leveled the playing field” to a great extent—bringing fans closer to celebrities, readers nearer to authors, and students approaching experts.

For patients and families, social media not only has provided opportunities for information gathering regarding specific disease states; in addition, many have found comfort in virtual communities with others who share their diagnoses and with whom they might share experiences and questions (27-29). Particularly astute medical and surgical groups have used these virtual communities to observe and better understand the information gaps and coping mechanisms present in their patient populations; these findings have then been used to further guide the social support aspect of patient care (30,31). Additionally, one study found that over 25% of patients in a surgical practice had used social media to aid in their surgeon selection (32).

For those in the medical community, social media—particularly Twitter—has served as a platform for continued and expanded dialogue beyond breakroom fodder and routine journal clubs. An exemplary example has been the success of the Thoracic Surgery Social Media Network (TSSMN) (33,34). This collaborative virtual group formed by the joint efforts of The Annals of Thoracic Surgery and The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery has 18 delegates and collectively over 53,000 followers. The TSSMN has been successful in bringing together medical professionals and trainees at all levels across the world for networking and dissemination of topical journal articles in the field of cardiothoracic surgery via TweetChat-based journal clubs (35). Additionally, recent results from a randomized trial demonstrated significantly improved Altmetric scores, Mendeley reads, and Twitter impressions when articles were tweeted versus control (non-tweeted), suggesting that this academic dialogue is impactful and long-lasting (36).

Importantly, the benefits of this digital forum are not limited to opportunities for scholarly discourse among learners and experts in the field of cardiothoracic surgery. Social media has additionally provided a much needed vehicle for women to share experiences and provide support in novel ways. Various blogs, such as those through the Association of Women Surgeons or Women in Thoracic Surgery, attract a great deal of internet traffic, with topics spanning all things from professional to personal life (37). These postings often provide personal stories in a form that is more accessible and intimate that a formal meeting, while also offering the convenience of the ability to view at any time.

Social media has offered more avenues for honest and open dialogue, and it has further been a significant impetus in the changing face of surgery today. In a predominantly male-dominated field, in which aspiring young surgeons may not have access to female mentors, the notion that “You can’t be what you can’t see” again becomes germane. With many female students feeling discouraged by the lack of visibility (or simply lack entirely) of exemplarily female role models, movements such as #ILookLikeASurgeon have brought strong female faces and names to the forefront, offering trainees the opportunity to see themselves in such roles (20-22,38). This was followed by #NYerORCoverChallenge, the overwhelming response fueled by a cover of The New Yorker, in which the four faces of the surgical team looking down upon a patient were exclusively women (39). This social media movement brought women together across surgical fields, dissolving hierarchical relationships, in a communal excitement to change stereotypes and represent the amazing identity of women surgeons.

Social media for networking, mentorship, and sponsorship

The importance of mentorship in the training of the next generation of surgeons is widely recognized. Effective mentorship has been reported to be associated with stress reduction, greater job satisfaction, confidence, research productivity, and promotion (40). A study to appraise mentorship in cardiothoracic surgical training demonstrated that 84% of cardiothoracic surgery residents had mentors, with the majority of respondents citing mentorship as critical to their success and career choice (41).

While women represent approximately half of graduating medical students, they continue to remain a minority in the surgical specialties, comprising 38% of surgical residents and less than 20% of full-time surgical faculty (21). Furthermore, this gender gap is more pronounced in surgical subspecialties such as cardiothoracic surgery, where women comprise of approximately 3% of total American Board of Thoracic Surgery certified diplomats and less than 5% of practicing cardiothoracic surgeons (8). Women in surgery often cite a lack of mentorship as a significant obstacle to career selection, progression, and satisfaction in the specialty (21,42,43), while valuing same-sex mentors as role models who assist them in succeeding in personal and professional career paths (41,44).

Social media allows for near instantaneous synchronous and asynchronous communication, breaking down the barriers of geography and time and can be a potent tool for not only networking and education, but also for promoting positive and diverse role models surgery (39). The #ILookLikeASurgeon (38), #NYerORCoverChallenge (39,45), and #HeForShe are examples of social media campaigns that have brought considerable attention to the role of women as surgeons and is changing stereotypes and highlighting the united community of surgeons (both women and men) in welcoming, educating, and supporting the future of surgery. In addition to increased awareness, social media can be a useful supplement to physician and trainee interactions, particularly for women in cardiothoracic surgery who may lack exposure to same-sex mentors at their own institution.

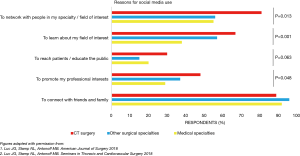

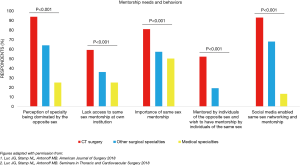

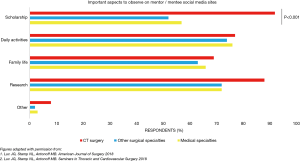

Although we do not yet have data to demonstrate that more women are entering surgical careers, specifically cardiothoracic surgery, as a result of social media engagement, prior literature has demonstrated the emerging role of social media for networking and mentorship. Previous studies published by our group in the American Journal of Surgery (44) and the Seminars in Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (46) have aimed to address this question. We have shown in a survey of 282 respondents (44,46) that individuals in different specialties use social media differently (Figure 1) with those in cardiothoracic surgery more likely to use social media to network with people in their specialty, learn about their field of interest and to promote their professional interests. Compared to medical and other surgical subspecialties, women in cardiothoracic surgery were more likely to find their field dominated by the opposite sex (cardiothoracic surgery 94% vs. other surgical specialty 64% vs. medical specialty 25%, P<0.001) and lack access to same sex mentorship at their own institution (cardiothoracic surgery 59% vs. other surgical specialty 36% vs. medical specialty 25%, P<0.001), though desire same sex mentorship (cardiothoracic surgery 81% vs. other surgical specialty 57% vs. medical specialty 50%, P<0.001). Importantly, compared to medical specialties, women in surgical specialties were more likely to report that social media has allowed them to build a larger network of same-sex mentorship than they could have been able to achieve (cardiothoracic surgery 93% vs. other surgical specialty 68% vs. medical specialty 13%, P<0.001) (Figure 2). We have also provided data in regards to important aspects sought on mentor/mentee social media sites (Figure 3).

It has been shown that a lack of sponsorship is keeping women from advancing in leadership in the business world (47,48) with women being over-mentored and under-sponsored (49). Social media can play a role in making connections for career advancement, even beyond mentorship, by becoming a modality by which one can build one’s brand (24), advocate for issues of personal interest (50) as well as network, role model, and offer sponsorship to other individuals (44,46). We have shown that social media can allow for remote attendance of academic meetings, with The Society of Thoracic Surgeons setting the standard to allow for alternative means for women on medical and parental leave to contribute to meetings (51). Given the increased use of social media for live-tweeting meetings (52) and bridging surgical scholarship to Twitter (53,54) through TweetChats (55) and community support (56), the potential uses of social media to create further unique opportunities to support women are limitless.

Moreover, we have demonstrated in a bibliometric analysis of the Annals of Thoracic Surgery that there has not only been a temporal trend towards improvement in female representation in authorship over the years, but, additionally, articles published by women were more likely to receive social media attention through Twitter (57). Social media attention has been shown to lead to higher article-level metrics (36) and citations in a recent prospective randomized controlled trial of tweeting articles through the Thoracic Surgery Social Media Network (58). Given that publications and citations were lower for women in surgical subspecialties compared to men and often cited as a potential barrier for promotion of women, this finding has particular relevance (17). Social media may provide a platform through which individuals can advocate and promote their work and the work of others, with specific utility for women to break the glass ceiling given, given that research productivity and impact are benchmarks of achievement often used as metrics for promotion in academic medicine (17).

Looking toward the future

Social media is constantly evolving, and, as we look toward the future, it is clear that the breadth, reach, and means of accessing social media will continue to change. While none of us has a crystal ball to predict the future, there are some expectations of how social media in the coming years may progress. While some of the predictions center around issues such as security, type of content (more videos), and less need for typing, some very likely forecasts emphasize the future role of mobile access (59). With more than 3 billion people in possession of mobile phones in 2020, it is clear that even busy surgeons will have greater ability to be engaged on such platforms along with the rest of the world’s growing social media savvy population (59).

Given social media’s broad reach and rapidly increasing potential for privacy and professionalism breaches, organizational bodies including the American Medical Association (60), American College of Surgeons (61) and the Cardiothoracic Ethics Forum comprised of membership of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery Ethics Committee and The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Standards and Ethics Committee (62,63) have published guidelines for ethical standards and use of social media for physicians and surgeons. Such guidelines will be especially emphasized as we consider the future roles of social media in our profession.

In addition, as the role of social media changes, we will see simultaneous progression of women in surgery. It is critical to recognize that, in consideration of the gender gap in medicine, the playing field has still not been leveled (64). Complete gender parity may not be necessary to change culture, as it is believed that when 20–30% of a group is comprised of women, their voices begin to be heard (65). Fortunately, despite the fact that women only comprise about 5% of our workforce, we do expect that, with time, we will reach a critical mass, and, perhaps, the need for external same-sex mentors will become de-emphasized. However, with the parallel growths in social media and digital networking, it is likely that such means of interaction will still be important components of rounding out one’s armamentarium of mentors and sponsors, even if for reasons other than finding networks of role models and colleagues of the same gender.

Conclusions

Social media has an important role in networking and mentorship, particularly for women in cardiothoracic surgery. In addition, social media can facilitate professional interactions, collaboration, development of online reputations, engagement in continued education, dissemination of new research findings, and public education. The utility of social media is wide and its effects far-reaching. Future studies are needed to establish the durability of social media and predictors in its effectiveness in achieving its goals.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (Cecilia Pompili and Leah Backhus) for the series “Women in Thoracic Surgery” published in Journal of Thoracic Disease. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jtd.2020.04.11). The series “Women in Thoracic Surgery” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. MA serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Journal of Thoracic Disease from Aug 2019 to Jul 2021. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- More Women Than Men Enrolled in U.S. Medical Schools in 2017. 2017. Available online: https://news.aamc.org/press-releases/article/applicant-enrollment-2017/. Accessed March 8, 2019.

- AAMC. Physician Specialty Data Report. 2016;2016.

- Ali AM, McVay CL. Women in Surgery: A History of Adversity, Resilience, and Accomplishment. J Am Coll Surg 2016;223:670-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- AAMC. State Physician Workforce Data Report. Available online: https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/report/state-physician-workforce-data-report. Accessed February 12, 2020.

- Carter JV, Polk HC Jr, Galbraith NJ, et al. Women in surgery: A longer term follow-up. Am J Surg 2018;216:189-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- AAMC. Active Physicians by Sex and Specialty, 2017. 2017. Available online: https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/active-physicians-sex-and-specialty-2017. Accessed January 30, 2020.

- Urschel HC Jr. Contributions of women to general thoracic surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2001;71:S14-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Antonoff MB, David EA, Donington JS, et al. Women in Thoracic Surgery: 30 Years of History. Ann Thorac Surg 2016;101:399-409. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Scott RP. Women in thoracic surgery: an ancient tradition and a new milestone. Ann Thorac Surg 2000;69:11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marks IH, Diaz A, Keem M, et al. Barriers to Women Entering Surgical Careers: A Global Study into Medical Student Perceptions. World J Surg 2020;44:37-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grobelna MK, Stepak H, Kolodziejczak B, et al. Career in vascular surgery - the medical student's perspective. Pol Przegl Chir 2017;89:33-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dixon A, Silva NA, Sotayo A, et al. Female Medical Student Retention in Neurosurgery: A Multifaceted Approach. World Neurosurg 2019;122:245-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mulcahey MK, Nemeth C, Trojan JD, et al. The Perception of Pregnancy and Parenthood Among Female Orthopaedic Surgery Residents. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2019;27:527-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Foote DC, Meza JM, Sood V, et al. Assessment of Female Medical Students' Interest in Careers in Cardiothoracic Surgery. J Surg Educ 2017;74:811-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Silver JK, Slocum CS, Bank AM, et al. Where Are the Women? The Underrepresentation of Women Physicians Among Recognition Award Recipients From Medical Specialty Societies. PM R 2017;9:804-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Greenberg CC. Association for Academic Surgery presidential address: sticky floors and glass ceilings. J Surg Res 2017;219:ix-xviii. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Valsangkar N, Fecher AM, Rozycki GS, et al. Understanding the Barriers to Hiring and Promoting Women in Surgical Subspecialties. J Am Coll Surg 2016;223:387-98.e2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carr PL, Raj A, Kaplan SE, et al. Gender Differences in Academic Medicine: Retention, Rank, and Leadership Comparisons From the National Faculty Survey. Acad Med 2018;93:1694-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Olive JK, Preventza OA, Blackmon SH, et al. Representation of Women in The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Authorship and Leadership Positions. Ann Thorac Surg 2020;109:1598-604. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schmidt LE, Cooper CA, Guo WA. Factors influencing US medical students' decision to pursue surgery. J Surg Res 2016;203:64-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Faucett EA, McCrary HC, Milinic T, et al. The role of same-sex mentorship and organizational support in encouraging women to pursue surgery. Am J Surg 2017;214:640-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Retrouvey H, Gdalevitch P. Women Plastic Surgeons of Canada: Empowherment Through Education and Mentorship. Plast Surg (Oakv) 2018;26:145-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Corsini EM, Boeck M, Hughes KA, et al. Global Impact of Social Media on Women in Surgery. Am Surg 2020;86:152-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Antonoff MB. Using social media effectively in a surgical practice. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2016;151:322-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Margolin DA. Social media and the surgeon. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2013;26:36-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brown J, Ryan C, Harris A. How doctors view and use social media: a national survey. J Med Internet Res 2014;16:e267. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hawkins CM, DeLa OA, Hung C. Social Media and the Patient Experience. J Am Coll Radiol 2016;13:1615-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- des Bordes JKA, Foreman J, Westrich-Robertson T, et al. Interactions and perceptions of patients with rheumatoid arthritis participating in an online support group. Clin Rheumatol 2020;39:1775-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Muhammad S, Allan M, Ali F, et al. The renal patient support group: supporting patients with chronic kidney disease through social media. J Ren Care 2014;40:216-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- De Silva D, Ranasinghe W, Bandaragoda T, et al. Machine learning to support social media empowered patients in cancer care and cancer treatment decisions. PLoS One 2018;13:e0205855. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huestis MJ, Kahn CI, Tracy LF, et al. Facebook Group Use among Parents of Children with Tracheostomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2020;162:359-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Curry E, Li X, Nguyen J, et al. Prevalence of internet and social media usage in orthopedic surgery. Orthop Rev (Pavia) 2014;6:5483. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Luc JGY, Ouzounian M, Bender EM, et al. The Thoracic Surgery Social Media Network: Early Experience and Lessons Learned. Ann Thorac Surg 2019;108:1248-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Luc JGY, Ouzounian M, Bender EM, et al. The Thoracic Surgery Social Media Network: Early experience and lessons learned. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2019;158:1127-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ni hIci T, Archer M, Harrington C, et al. Trainee Thoracic Surgery Social Media Network: Early Experience With TweetChat-Based Journal Clubs. Ann Thorac Surg 2020;109:285-90.

- Luc JGY, Archer MA, Arora RC, et al. Social Media Improves Cardiothoracic Surgery Literature Dissemination: Results of a Randomized Trial. Ann Thorac Surg 2020;109:589-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhao JY, Romero Arenas MA. The surgical blog: An important supplement to traditional scientific literature. Am J Surg 2019;218:792-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hughes KA. #ILookLikeASurgeon goes viral: How it happened. Bull Am Coll Surg 2015;100:10-6. [PubMed]

- Antonoff MB, Stamp N. The #NYerORCoverChallenge: What it means for women in cardiothoracic surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2017;154:1349-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusic A. Mentoring in academic medicine: a systematic review. JAMA 2006;296:1103-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stephens EH, Goldstone AB, Fiedler AG, et al. Appraisal of mentorship in cardiothoracic surgery training. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2018;156:2216-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Park J, Minor S, Taylor RA, et al. Why are women deterred from general surgery training? Am J Surg 2005;190:141-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cochran A, Melby S, Neumayer LA. An Internet-based survey of factors influencing medical student selection of a general surgery career. Am J Surg 2005;189:742-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Luc JGY, Stamp NL, Antonoff MB. Social media in the mentorship and networking of physicians: Important role for women in surgical specialties. Am J Surg 2018;215:752-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pitt SC. What does #NYerORCoverChallenge mean for men in cardiothoracic surgery? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2017;154:1352-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Luc JGY, Stamp NL, Antonoff MB. Social Media as a Means of Networking and Mentorship: Role for Women in Cardiothoracic Surgery. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2018;30:487-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tesch BJ, Wood HM, Helwig AL, et al. Promotion of women physicians in academic medicine. Glass ceiling or sticky floor? JAMA 1995;273:1022-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ibarra H. A Lack of Sponsorship Is Keeping Women from Advancing into Leadership. 2019. Available online: https://hbr.org/2019/08/a-lack-of-sponsorship-is-keeping-women-from-advancing-into-leadership. Accessed 19 Feb 2020.

- Ibarra H. Women Are Over-Mentored (But Under-Sponsored). 2019. Available online: https://hbr.org/2010/08/women-are-over-mentored-but-un. Accessed 19 Feb 2020.

- Stamp NL, Luc JGY, Ouzounian M, et al. Social media as a tool to rewrite the narrative for women in cardiothoracic surgery. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2019;28:831-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Antonoff MB. Opportunities for Academic Achievement During Parental Leave: The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Sets the Standard. Ann Thorac Surg 2018;106:321-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Luc JGY, Antonoff MB. Live Tweet The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Annual Meeting: How to Leverage Twitter to Maximize Your Conference Experience. Ann Thorac Surg 2018;106:1597-601. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Antonoff MB. Thoracic Surgery Social Media Network: Bringing Thoracic Surgery Scholarship to Twitter. Ann Thorac Surg 2015;100:383-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Antonoff MB. Thoracic Surgery Social Media Network: Bringing thoracic surgery scholarship to Twitter. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2015;150:292-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Luc JGY, Varghese TK Jr, Antonoff MB. Participating in a TweetChat: Practical Tips From The Thoracic Surgery Social Media Network (#TSSMN). Ann Thorac Surg 2019;107:e229-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Luc JGY, Antonoff MB. Bridging gaps in transition to practice. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2019;158:e177. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Luc JG, Percy ED, Hirji S, et al. Predictors of High-Impact Articles in The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons 56th Annual Meeting. January 25-28, 2020. New Orleans, LA, USA.

- Luc JGY, Archer M, Arora R, et al. Does Tweeting Improve Citations? One-Year Results from the TSSMN Prospective Randomized Trial. Ann Thorac Surg 2021;111:296-300. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chiaruain AN. What Will Social Media Look Like in the Future? 2019. Available online: https://blog.logograb.com/social-media-future/. Accessed 19 Feb 2020.

- AMA. Professionalism in the Use of Social Media. 2012. Available online: https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/ethics/professionalism-use-social-media. Accessed 17 Feb 2020.

- Logghe HJ, Boeck MA, Gusani NJ, et al. Best Practices for Surgeons' Social Media Use: Statement of the Resident and Associate Society of the American College of Surgeons. J Am Coll Surg 2018;226:317-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Varghese TK Jr, Entwistle JW 3rd, Mayer JE, et al. Ethical Standards for Cardiothoracic Surgeons' Participation in Social Media. Ann Thorac Surg 2019;108:666-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Varghese TK Jr, Entwistle JW 3rd, Mayer JE, et al. Ethical standards for cardiothoracic surgeons' participation in social media. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2019;158:1139-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Arora S, Galanos AN. The tipping point: academic careers of women in medicine today. Acad Med 2011;86:921-2; author reply 2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Newton J. Critical Mass: What Happens When Women Start to Rule the World. Harvard Kennedy School of Politics. Available online: https://iop.harvard.edu/get-involved/study-groups/critical-mass-what-happens-when-women-start-rule-world-led-jay-newton. Accessed 19 Feb 2020.