Women in thoracic surgery: perspectives from South America

Introduction

South America has an estimated population of 440 million people, mainly speaking two languages (Spanish and Portuguese) (1). Female participation in the labor force is lower than in Europe or North America, but it has increased over time. Currently, 52% to 74% of South American women ages 15 to 64 years are active workers (2). South American countries still carry the traditional legacy of predominantly male societies; the best opportunities and the highest salaries are offered to men. Worldwide, gender-related bias in the surgical specialties has been documented in several studies (3,4). Interestingly, the proportion of women in medical school is growing exponentially, including the number of women going into surgical specialties. However, gender opportunities are far from equal in South America. This text aims to describe the medical pathway to become a thoracic surgeon in South America and portray some of the difficulties that female surgeons face.

Medical academic journey in South America

The academic journey to a thoracic surgical career is quite similar among South American countries. Brazil is the largest country and contains half of the South American population. In Brazil, after high school is completed, candidates apply directly to a 6-year medical school program. As in the United States, medical schools in South America can be either private or public. To enter a program, candidates must take a national exam. General surgery residency is required, and Brazil lacks common trunk programs integrated with the thoracic surgery specialty. General surgery programs last 2 or 3 years, and the resident will rotate through several specialties. Interruption of residency training for a research fellowship is not permitted. Thoracic surgery residencies are two-year programs that include only general thoracic surgery; neither cardiac surgery nor esophageal surgery (with rare exceptions) are part of the programs. Further training after the thoracic surgical residency is optional. There are fellowship programs in lung transplant, minimally invasive surgery, lung cancer surgery, and airway surgery. If a master’s or doctoral degree is pursued, the surgeon usually starts that program after completing his or her surgical fellowship. It is more difficult to get a position in a general surgery residency than in an academic postgraduate program, justifying this typical order. There are small variations in this model across South American countries. For example, Uruguay has a 7-year medical school duration and 5-year thoracic surgery residency duration. In all countries, however, the pathway to complete thoracic surgery training is very long, as it probably should be.

Women in thoracic surgical residencies

Although the numbers of male and female medical students are well balanced, we cannot assume that this balance extends into surgical residency programs, in South America or worldwide. The lack of female mentors at academic positions might explain why fewer women pursue surgical careers as compared with their male peers. Additionally, during residency, effective median working hours are higher in surgical programs than in clinical specialties. Thereafter, the training period is longer compared with other specialties. These aspects are important when you want to start a family and advance in your academic career.

Because basic science research laboratories run by active surgeons are not common in most South American countries, there are not many opportunities to attract young students or promote residents into an academic career. Additionally, maternity leave is not well accepted as part of residency programs in South America and worse, is not seen as a natural part of a woman’s life. Only after 10 months of training the resident is entitled to receive maternity leave payment (5). Female residents can be mistreated or misjudged as someone that is letting the team understaffed. Female residents worldwide encounter challenges not faced by their male peers. For example, Meyerson and colleagues found a significant bias against female thoracic surgery residents in evaluations of operative autonomy from both residents and faculty. Residents reported that female faculty gave residents of both genders equal autonomy, while male faculty gave male residents more autonomy (6).

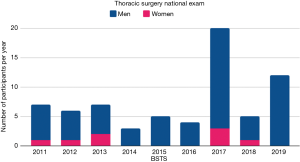

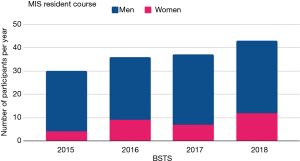

The number of residents in Brazil and their activities are a proxy for trends in the specialty in South America. Representation of women among thoracic surgical residents is much higher than a decade ago and continues to grow. The Brazilian Society of Thoracic Surgery (BSTS) is responsible for the thoracic surgery national exam that is equivalent to the United States thoracic surgery boards exam. In Brazil, however, you are not obligated to take the exam before starting your career. Since 2011, the percentage of national exam applicants who were women has ranged from 0% to 28.6% (Figure 1). The BSTS also sponsors a yearly minimally invasive surgery course offered to all second-year residents in the country that has over 95% attendance. In the past four years, female residents had a median participation of 21.9% (Figure 2). This data gives us some hope for changes in gender representation among Brazilian thoracic surgeons in the future.

Women in thoracic surgery in Brazil

The BSTS is a national society of board-certified, non-cardiac, thoracic surgeons. It has over 600 members (7). Society participation by women has varied over the years, and women have comprised a median 12% of the active members over time, according to the BSTS. Once every two years, the society organizes a national conference meeting. Gender bias has been evident at this meeting and is indicative of the surgical culture in Brazil. First, only a handful of females are invited for lectures. In contrast, oral abstracts, which are blinded selected, are equally presented by surgeons of both genders. Second, female surgeons will often be referred to by their first names when they are presenting or moderating instead of by their complete name as should be customary for any presenter or moderator. This behavior was analyzed systematically at a major surgical society meeting in the United States (8). Davids and colleagues reported an imbalance in the formality of speaker introductions between sexes at a colorectal surgery meeting. Female moderators were similarly formal when introducing male and female speakers; however, male moderators were significantly less likely to formally introduce a female colleague as compared with a male colleague (8).

Chief positions and full professor appointments in tertiary and university-affiliated hospitals are predominantly occupied by men in South America, as is also the case in the United States, Great Britain and Japan (9). In centers with more than one professor on the thoracic surgery service, a female surgeon might have the opportunity to advance her academic career.

As technology evolves within the Brazilian medical system, access to new platforms has also not been equal for male and female surgeons. Worldwide and in South America, robotic surgery is being adopted rapidly. Hospitals require the surgeon to complete training and obtain certification prior to starting to practice robotic surgery. This strategy allows the companies who manufacture the robotic equipment to identify the surgeons using the equipment and control the number of surgeons with privileges across the country. Unfortunately, fewer than 5% of robotic thoracic surgeons in Brazil are women. The male-female ratio of robotic surgeons in Brazil is low, again reflecting a huge disparity in opportunities between the genders (non-published data from the BSTS).

Additional problematic situations

We have encountered additional situations that exemplify a lack of respect and understanding that we believe are worth noting. In the first, a pregnant faculty attendee was rounding with colleagues and residents. One of her colleagues said “Watch out, at any minute she could give birth like a brooder hen”. This type of joke has become so common that people simply accept it and laugh. Although it was not meant to be an aggressive comment, it was completely improper. After a female surgeon gives birth and becomes a new mom, she will hear things like “you can’t count on her, you never know when her baby will be sick”. Both are examples of a lack of respect, unfortunately seen in several South American countries.

A woman may choose to postpone pregnancy or freeze her eggs to preserve her fertility. The process of egg freezing usually demands an entire month, with two or three visits to the fertility center during stimulation of ovulation. When the time comes to collect the eggs, it is not possible to anticipate or postpone the date. A flexible surgical schedule and colleagues who will cover her work are required, but the female surgeon may encounter resistance or resentment in meeting this demand.

Future perspectives

Women in Thoracic Surgery (WTS) is the only professional society dedicated to female surgeons. Both authors have benefitted from their involvement with WTS. Surgeons of any gender can be members; however, we reach out to female thoracic surgeons nationally and internationally. The society aims to mentor and enhance educational opportunities for young women thoracic surgeons. International exchange programs and academic research are also promoted by WTS. As a unique society, this facilitates our communication and helps us grow stronger. One of the best ways to increase the number of women in leadership positions is through quality medical care provided to patients by female thoracic surgeons.

There is a strong support from major international thoracic surgery societies to change the role of women in thoracic surgery, allowing them to have equal opportunities. WTS is actively conducting research into how we can make the thoracic surgery specialty more attractive to women. We also need more female role models to encourage and help female students and residents to pursue this amazing career.

Guidelines specific to address and overcome gender-related implicit bias in surgical resident education have been published in the United States (10). In South America, the presence of unconscious bias should at least be addressed in order to start changing the culture and give a fair and equal education to male and female residents.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Luis Eduardo Liguera Soza, Brazilian Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (Cecilia Pompili and Leah Backhus) for the series “Women in Thoracic Surgery” published in Journal of Thoracic Disease. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jtd.2020.04.12). The series “Women in Thoracic Surgery” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Available online: https://countrymeters.info/en/South_America

- Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.TLF.ACTI.FE.ZS?name_desc=false&view=map

- Rohde RS, Wolf JM, Adams JE. Where Are the Women in Orthopaedic Surgery?. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2016;474:1950-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Capdeville M. Gender Disparities in Cardiovascular Fellowship Training Among 3 Specialties From 2007 to 2017. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2019;33:604-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Available online: http://portal.mec.gov.br/index.php?option=com_docman&view=download&alias=9466-perguntasfrequentes-bolsaelicencamaternidade&category_slug=novembro-2011-pdf&Itemid=30192

- Meyerson SL, Sternbach JM, Zwischenberger JB, et al. The Effect of Gender on Resident Autonomy in the Operating room. J Surg Educ 2017;74:e111-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://sbct.org.br/

- Davids JS, Lyu HG, Hoang CM, et al. Female Representation and Implicit Gender Bias at the 2017 American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons' Annual Scientific and Tripartite Meeting. Dis Colon Rectum 2019;62:357-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Epstein NE. Discrimination against female surgeons is still alive: Where are the full professorships and chairs of departments? Surg Neurol Int 2017;8:93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hemphill ME, Maher Z, Ross HM. Addressing Gender-Related Implicit Bias in Surgical Resident Physician Education: A Set of Guidelines. J Surg Educ 2020;77:491-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]