Women in thoracic surgery: European perspectives

Introduction

In medical schools throughout Europe, women are representing an increasing proportion of graduates entering the medical profession. Even though this phenomenon is also found in the surgical profession, women are still clearly underrepresented, in particular in leadership positions. It is difficult to depict a singular experience reflective of all of Europe, as differences in culture, medical systems and government policies may have affected the women choices during their medical career. However, there might be additional reasons for this gender gap related to the fact that diversity has not arrived yet in our specialty.

In a recent survey, women reported significantly more discrimination during their cardiothoracic residency training than their male counterparts (1). According to this evaluation reporting intraoperative autonomy among thoracic surgery residents using the Zwisch scale, faculty reported that female residents had less autonomy than male residents (30% vs. 37%). In addition, female residents self-reported lower autonomy compared to male residents (19% vs. 33% with meaningful autonomy).

Regarding surgical confidence, female residents were less likely to self-identify as a “surgeon” (11% vs. 38%) (2). They felt their professional role was disregarded more often by patients and physicians.

Microaggressions & burnout are phenomena that typically occur in the work and life of a surgeon. However, surveys have found that the prevalence of burnout may be as much as 20% to 60% higher among women physicians than among men physicians (3,4).

This is despite the fact that female health care providers are perceived as more alert with a greater tendency to stick to clinical guidelines thus being more likely to deliver evidence-based treatment and better communication with patients and families. In general, female doctors display more empathy for their patients, who in effect appear to share more medical and psychosocial information and make more supportive statements (5). The mechanism behind better outcomes for patients treated by female surgeons might be related to delivery of care that is more compliant with standard, more patient-centered, and involves superior communication (5-8).

Women surgeons face challenges in both training and practice. It has been shown that the “surgical personality”, surgical culture, and sexism, as well as factors of lifestyle and workload, are deterrents for women considering a surgical career. In addition, difficulty in identifying mentors due to the lack of women in surgical leadership may exacerbate the difficulties. These barriers may result in a selection of women with higher standards to gain entrance into the surgical workforce than men, with women more skilled, motivated, and harder working.

In a recent UK survey of women in surgery of all specialties, they found that 88% felt surgery was still male dominated, 59% reported or witnessed discrimination against women in the workplace, and that there was a lack of flexibility with 34% feeling that the profession was not conducive to motherhood (9).

Women are also a minority in surgical academia. Furthermore, female academics report greater social isolation than men, and they are less integrated into university departments. Women report more difficulties with relationships with colleagues, and more leave their positions because of negative relationships (10). One strategy that women academics employ leads them to strive to be incredibly conscientious and dedicated, putting excess pressure on themselves.

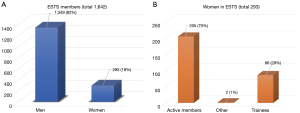

The European Society of Thoracic Surgeons (ESTS) involves 1,642 members including 18% female across all membership types: in particular, 70% of the female members are active, 29% are trainees and only one honorary member (Figure 1). Increasing number of initiatives, however, like the first ESTS Women in Thoracic Surgery Scientific Session or the annual Women in Thoracic ESTS Reception during the Annual Conference, are done in an effort to encourage all female colleagues to join this specialty and increase the opportunity to share their experience and meet potential mentors.

In this article we describe the situation in some of the European countries whose female thoracic surgeons have led the way. We aim to give the next generation examples that can influence women’s choice of surgical career, and the possible strategies and initiatives to reduce the gender discrimination within healthcare.

Gender gap in medical professional career including thoracic surgery: the Italian situation

In these paragraphs we analyze some aspects of gender discrimination at work in Italy with a focus on the situation of women in thoracic surgery compared to other European and international countries.

What is the gender pay gap in Italy?

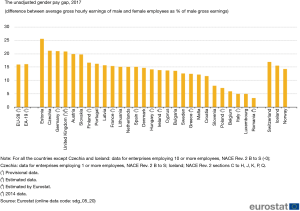

The gender pay gap is the difference in average gross hourly wage between men and women across the economy. In Italy the gender pay gap stands at 5.3% vs. 16% in Europe (11). In 2017, the highest gender pay gap in the EU was recorded in Estonia (25.6%) and the lowest in Romania (3.5%). The highest gender pay gap is in financial and insurance industries, and is higher in the private sector than in the public. Smaller gender pay gap is seen among younger employees.

Figure 2 shows the unadjusted gender pay gap in 2017 in terms of difference between average gross hourly earnings of male and female employees as % of male gross earnings (11).

The gender gap in earnings is the difference between the average annual earnings between women and men. The overall earning gap in Italy is –43.7% compared to men an is worse than in Europe overall which is –39.6%. This situation is related to different types of disadvantages that women have to face. Lower hourly earnings working fewer hours in paid jobs, women more often work part-time and they work in lower paid sectors lower employment rates because often have to take the primary responsibility for care of their families. They are also confronted with the corporate glass-ceiling (Eurostat, 2016). We must consider that in Europe only 6.3% of CEO are women.

Women in thoracic surgery: the situation in Italy

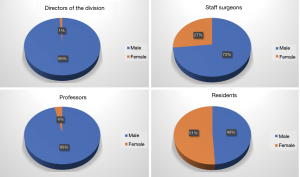

In January 2020 a letter was sent by the Society of Thoracic Surgery in Italy to all the directors of divisions asking to report the number of female and male surgeons in the staff of Thoracic Surgery Divisions or Units they directed. In addition, we asked for the number of female or male residents in the Thoracic Surgery Schools and recorded the numbers of associate or full professors from the registry of the Ministry of Education, University and Research (MIUR). The results are reported in the Figure 3. Data were recorded in 34 Italian centers out of 81 Units or Divisions representatives of the three area of North Italy, Centre and South Italy.

While the residents are equally distributed in the two genders 51% and 49%, staff surgeons are more represented by male (73% male vs. 27% female). The situation in the academic positions are even more unbalanced versus male gender which represents the 96% of the professors with only 2 female associate professors out of 56. The leadership position is a rarity for women surgeons in Italy with only 1 Director of Unit out of 82 Units in the territory.

The Italian data confirm a situation far from parity and equality for women to enter the professional world of thoracic surgery despite equal number of women represented in surgical schools. Much like in the US, the difference even larger in Italian academia.

A paper published in the Annals of Internal Medicine explored gender domestic roles and responsibilities of physicians in academia. Jolly and colleagues (12) hypothesized that differences in nonprofessional responsibilities may partially explain the gap in career success between female physician researchers and male counterparts. The survey study was carried among 1,049 physicians with a current affiliation to a U.S. academic institution and research role. These physicians were selected to participate in the survey based upon recent National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant awards of K08 and K23, between the years 2006 to 2009. Time spent on parenting and domestic tasks was determined through self-report among married or partnered respondents with children. Women spent 8.5 more hours per week on domestic and parenting activities than men after adjustments for work hours, spousal employment, and other factors. Women in the study were more likely to have partners who worked full-time at a rate of 85.6% compared to men at 44.9%. More interestingly, female gender was independently associated with less time spent on research and women were more likely to report taking time off during disruptions of usual child care arrangements (e.g., sick child). The authors hypothesized that this could be a hindrance to advancement of female academic career. Other areas, like patient teaching time or clinical care time were not impacted. Most certainly, research time will directly affect academic success and achievement.

There is still considerable distance to achieve parity and equity for women in thoracic surgery in Italy. The pipeline, however, is now more robust, with a steady stream of qualified individuals representing female gender even in surgical professions. To promote gender equity, we advocated for more work place child care services, since the burden of these duties falls unto women. A change in the culture access to child care resources could free up these high-level professionals to focus more on work and allow less worry and guilt felt by many mothers.

Gender gap in medical professional career including thoracic surgery: the Spanish situation

Spain was different

Spaniards used to say “Spain is different” to explain many things that happen in our country. However, in this matter, this may be true. It is well-known that the Spanish social security system is equalitarian not only for patients but also for doctors. After medical school, the applicant meets their future peers at the national board examination. This exam will give him/her the chance to choose among available positions around the country depending on test results and preferences. Once into the system, there are no differences on salary or working conditions between men and women. However, working circumstances depend on the head and staff of the unit the applicant will be working in.

In 1976, the first Spanish female thoracic surgeon started her residency training in Barcelona. After in 1990, there were two females already with independent practice and four more in training in different hospitals mainly located in the Madrid area. Although female surgeons were increasing in 1998, still our male counterpart was overwhelming (Figure 4).

Current situation of female thoracic surgeons in Spain

Over the past two decades the proportion of women entering medical school in Spain has increased dramatically, such that more than half of today’s graduating medical students are women. Moreover, in 2017, the number of female registered medical practitioner overcame the number of male doctors for the first time. And in the last national board examination [2019], 64.1% of applicants were women. Similarly, the proportion of females entering surgical residency is growing, albeit at a slower rate than what has been observed in medical schools. Regarding Thoracic Surgery residency program, in the latest national board examination, 65.4% of doctors who chose this specialty were female. Thus, our specialty is becoming increasingly more attractive among women. Today, Spain has 275 thoracic surgeons, of whom 38.7% are women. According to the Ministry of Health, in 2025, this number will decrease due to retirements to an estimated 44.5% female.

Thoracic Surgery residency training in Spain is 5 years and has a rigorous career path that requires an average of 60-hour workweeks (7.5-hour weekday and one 24- or 17-hour shift). Training starts, for most, in their mid-20s and finishes into their early 30s. The residency is not just physically taxing (a resident spends most of the day on her feet and a lot of hours without eating or even drinking water), it also takes a psychological toll. Although equity is guaranteed and gender disparities do not affect work schedules and salaries, getting good surgical training depends on the participation and dedication of the residents more than the environment. The surgical resident life includes lifestyle changes with little flexibility to accommodate personal or family responsibilities and this circumstance continues throughout their professional life. This is the reason why some young doctors perceive an inability to achieve work-life balance in the surgical specialties and this is also the reason why women are more prone than their male counterparts to reject a surgical career due to a desire to have children.

Regarding motherhood, in Spain, parental leave varies between men and women. For women, it lasts 16 weeks, meanwhile at present it lasts only 12 weeks for men. This period will increase up to 16 weeks in 2021 in an attempt of the government to achieve a real equity between males and females. Transitioning from maternity leave back to clinical work can be tough, making childcare, breastfeeding and even sleep a challenge. In general, hospitals are not prepared for female doctors who breastfeed and sometimes can be difficult to find the perfect place and time to pump milk and store it properly in a secure space. Moreover, family support or childcare providers are indispensable to survive the first years of parenthood. But even being hard, many surgeons think parenthood is worth it. One typical worry is that motherhood might take away “edge” or even the focus of a surgeon. Instead, having children, frequently makes women surgeons more empathetic and attuned to patient and colleagues needs.

Historically, there has been a lack of female role models and mentors in the surgical specialties in Spain. Mentorship is important since experienced surgeons can help medical students, residents and young attending surgeons to navigate their career paths and give advice. Although male doctors can be excellent mentors for women, having strong female role models can be helpful to identify and overcome challenges unique to women. Fortunately, in recent years, the number of women surgeons available to act as mentors and role models is increasing progressively in Spain.

Finally, although the rise in the number of women choosing a career in surgery is encouraging, the number of women surgeons in positions of power continues to be low. For instance, the young Spanish Society of Thoracic Surgery (SECT) was officially created in 2009. In more than 10 years of history, no woman has achieved any position of leadership. Only two thoracic surgical units are led by women. Similarly, at the ESTS founded in 1993, there has only been one woman president in the history of this society (Dr. Gunda Leschber) and among the 32 honorary members, there is only one woman (Dr. Valerie Rush). However, the number of female members of the Board of Directors has increased as has the number of female members of the society.

Gender gap in medical professional career including thoracic surgery: the Swiss situation

The Swiss diversity

The under-representation of female (thoracic) surgeons in Switzerland mirrors the statistics from the countries mentioned above: The Swiss Society of Thoracic Surgery has a total of 71 members, of which there are 6 females (8.5%) [in comparison the German Thoracic Society (DGT) with 675 members of which there are 150 females (22%)]. On the other hand, the trend towards a majority of female medical students seems to be the same throughout Europe and other parts of the world, and this is indeed a great development in comparison to a century ago. Furthermore, female doctors in general are not a rarity anymore, at the resident level the percentage of women (58.6%) is even higher (13), but in many subspecialties women are still largely underrepresented. In Switzerland men, compared to women, make up the majority in the surgical field (thoracic surgery 94.3%, orthopedic surgery 90.0%, vascular surgery 87.7%, heart and thoracic vascular surgery 87.7%, neuro surgery 85.7%, urology 85.0%) (14). Furthermore, the translation into leadership positions in academic surgery is still very rare. In Switzerland, looking at all specialties, the number of female physicians declines with ascending hierarchy or higher leadership levels. At the level of junior attending physicians there are 47.9% females, at the level of senior attending physicians 24.5%, and at the level of head physicians there are only 12.4% females (14).

The situation in Germany is similar. Even though more females than males start studying medicine, many female physicians end their further education without a specialist degree. Among head physicians and senior attending physicians, females are clearly underrepresented, especially in surgery. But there is an increasing trend over the past decades: in general surgery, the percentage of female surgeons in 1930 was 2%. In 1956, it increased to 3.1%, in 1996 it was 11.8%, and in 2000 it was 14.1%. As mentioned, the trend is increasing—but, in absolute numbers, there were 4,128 female surgeons compared to 16,086 male surgeons—in 2013 (statistics of BÄK 2013).

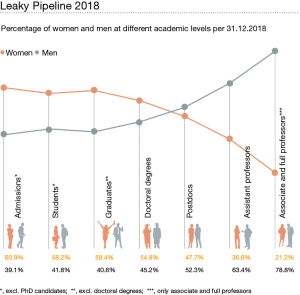

Taking the discussion into the academic environment, the statistics show a clear difference not only at the level of full professors but also at the level of lecturers or assistant professors as depicted in the gender monitoring figure of the University of Zurich (Figure 5).

The attrition of women on their pathway from graduation to leadership academic positions might be explained in part, by heavy workload in balancing clinical, research, and teaching activities combined with the lack of domestic support.

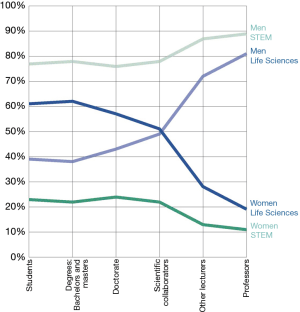

This “leaky pipeline” is particularly strong in the life sciences. In science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM), the dropout rate is less marked, but the proportion of women is much lower from the outset (Figure 6).

These figures and facts lead to numerous initiatives in different countries in order to overcome these barriers—being cultural, social, institutional, and/or personal—and this can be indeed very supportive for the next generation of female surgeons, doctors, or any female professionals.

Medicine and surgery in particular, is also biased with historical gender images and mentally associated with a professional “ethos of permanent availability”, implying long and atypical working hours, which by definition are difficult to align with a family.

Therefore, the task for our generation will be to remove some of these barriers, both personal and institutional: the first responsibility lies in hiring strategies to influence gender composition of the staff-personal and institutional biases have to be overwhelmed. The next step will be to introduce working models allowing adequate training and fulfilling the role as a mother, wife, daughter, sister, etc. This might be the biggest challenge to implement these models by complying to working hours restrictions and training requirements in highly specialized fields, such as thoracic surgery. But, even in surgery, there are options for part-time engagement. Besides classical part-time work (50% employment), there are possibilities to work 60%, 75%, or 80%. The arrangement of those close-to-full-time part-time employments is to be adapted to the needs of the employee: working days with reduced hours or full days with 1–2 free days per week to accommodate for taking care of children or relatives in need. The duration of training will however be expanded, when done on a part-time basis.

Part-time employments can also be identified in specially defined work areas. These are particularly an option for physicians after their specialist training is finished; e.g., ambulatory surgery setting or specializing in highly elective operations (e.g., thyroid surgery).

Other strategies must come from higher institutional levels, including local and national government. The Swiss National Science Foundation sets a great example here by complementing efforts by all stakeholders in the system and the measures here focus on the postdoctoral level by providing excellence grants for female doctoral candidates in life sciences.

Gender gap in medical professional career including thoracic surgery: the UK situation

Women are underrepresented in the surgical specialties in the UK despite more women than men qualifying from medical schools for many years. The situation has improved, but progress has been very slow over the last three decades. The percentage of female consultant surgeons across all specialties has risen from 3% in 1991 to 12.9% in 2019 (15). In Cardiothoracic Surgery only 10% of consultant posts are held by women (the majority of these are thoracic surgeons, with only 11 cardiac surgeons and 2 congenital cardiac surgeons as of May 2020). Reassuringly, the number of women in training has increased year over year.

The Royal College of Surgeons of England (RCS) actively promotes surgery as a career open to people of all backgrounds. Women in Surgical Training (WiST) was launched in 1991, and is now known as Women in Surgery (WinS)—its mission statement is to encourage, enable and inspire women to fulfil their surgical potential (https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/careers-in-surgery/women-in-surgery/). This is done through a variety of initiatives including hosting networking events, conferences, sharing positive images and stories of women surgeons across all grades and specialties, as well as practical advice on issues such as pregnancy and parenthood. ‘Normalizing’ working less than full time (if wished) and taking time out for maternity leave should encourage women not seeing family life and a surgical career as mutually exclusive. The need for support does not end with the training years; stepping up into leadership roles can also be a hurdle when juggling other priorities. To address this, RCS launched the Lady Estelle Wolfson Emerging Leaders Fellowship in 2015, which provides fellows with access to mentors and leadership skills. Social media including Facebook, twitter and more recently Instagram has allowed the WinS message to reach a wider audience, and interact with our global colleagues, whether that is sharing opportunities or joining in powerful campaigns such as #ILookLikeASurgeon or #HeForShe.

Within Cardiothoracic Surgery, a number of professional bodies [The Society for Cardiothoracic Surgery (SCTS), the Specialist Advisory Committee (SAC) and the Intercollegiate Specialty Board (ISB)] work together to ensure objectivity in terms of recruitment into national training, quality of training, and standards for examinations (16). This also includes having a diverse range of interviewers, examiners and striving for balanced panels on courses and at conferences—thus ensuring visible role models of different genders, ethnicities and intersectionality. The latter cannot be underestimated in its importance, and nor can the support of our male colleagues in achieving an improvement in numbers of women surgeons.

In summary, whilst only 10% of cardiothoracic surgeons in the UK are women (and the proportion is far lower for cardiac surgeons), things are improving, albeit slowly. Great strides are being made to encourage women into our specialty, understanding the issues they face and supporting them in their careers. Cardiothoracic Surgery needs these women—they are valuable and vital members of our surgical workforce.

Conclusions

This paper provides important insights about the ways in which single countries have faced the gender gap in surgery. There is a clear overall improvement in numbers of female surgeons among these countries which should encourage the new students and young clinicians who to pursue personal aspirations in the surgical field.

The academic career seems to be the one most affected by concerns about work-life balance (17,18), but the understanding of the shared experience may help mentors and mentees to overcome the gender bias’s obstacles. The development of female surgical associations, mentorship programmes and national initiatives will further champion the gender equality in this specialty across Europe.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Italian Society of Thoracic Surgery (SICT) and the Directors of the Italian Divisions of Thoracic Surgery to have participated to the survey.

Finding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the editorial office, Journal of Thoracic Disease for the series “Women in Thoracic Surgery”. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jtd-2020-wts-09). The series “Women in Thoracic Surgery” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. CP served as an unpaid Guest Editor of the series and serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Journal of Thoracic Disease from Sept 2018 to Aug 2020. Dr. GV reports grants from Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC), Ministry of Health, Istituto nazionale Assicurazione Infortuni sul Lavoro (INAIL), personal fees from Medtronic, personal fees from Ab Medica, personal fees from Johnson & Johnson, outside the submitted work. The other authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Meyerson SL, Sternbach JM, Zwischenberger JB, et al. The effect of gender on resident autonomy in the operating room. J Surg Educ 2017;74:e111-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Myers SP, Hill KA, Nicholson KJ, et al. A qualitative study of gender differences in the experiences of general surgery trainees. J Surg Res 2018;228:127-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McMurray JE, Linzer M, Konrad TR, et al. The work lives of women physicians results from the physician work life study. The SGIM Career Satisfaction Study Group. J Gen Intern Med 2000;15:372-80. [PubMed]

- Dimou FM, Eckelbarger D, Riall TS. Surgeon burnout: a systematic review. J Am Coll Surg 2016;222:1230-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Roter DL, Hall JA, Aoki Y. Physician gender effects in medical communication: a meta-analytic review. JAMA 2002;288:756-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Frank E, Dresner Y, Shani M, et al. The association between physicians' and patients' preventive health practices. CMAJ 2013;185:649-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lurie N, Slater J, McGovern P, et al. Preventive care for women. Does the sex of the physician matter? N Engl J Med 1993;329:478-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bertakis KD, Helms LJ, Callahan EJ, et al. The influence of gender on physician practice style. Med Care 1995;33:407-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bellini MI, Graham Y, Hayes C, et al. A woman's place is in theatre: women's perceptions and experiences of working in surgery from the Association of Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland women in surgery working group. BMJ Open 2019;9:e024349. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carr PL, Gunn CM, Kaplan SA, et al. Inadequate progress for women in academic medicine: findings from the National Faculty Study. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2015;24:190-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boll C, Lagemann A. The gender pay gap in EU countries—new evidence based on EU-SES 2014 data. Intereconomics 2019;54:101-5. [Crossref]

- Jolly S, Griffith KA, DeCastro R, et al. Gender differences in time spent on parenting and domestic responsibilities by high-achieving young physician-researchers. Ann Intern Med 2014;160:344-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hostettler S, Kraft E. FMH Aerztestatistik 2018: Wenig Frauen in Kaderpositionen. Schweiz Ärzteztg 2019;100:411-6.

- Verbindung der Schweizer Ärztinnen und Ärzte FMH. FMH-Ärztestatistik: Frauen- und Ausländeranteil als Schlüsselfaktoren, Gefälle bei Ärztedichte. 2016. Available online: https://www.tellmed.ch/tellmed/Presse/FMH_Aerztestatistik_Frauen_und_Auslaenderanteil_als_Schluesselfaktoren_Gefaelle_bei_Aerztedichte.php

- Royal College of Surgeons of England. Statistics: Women in surgery. 2019. Available online: https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/careers-in-surgery/women-in-surgery/statistics/

- Specialty Advisory Committee and the Society for Cardiothoracic Surgery in Great Britain and Ireland. UK Cardiothoracic Surgery, Workforce report 2019. 2019. Available online: https://scts.org/released-workforce-report-2019/

- Strong EA, De Castro R, Sambuco D, et al. Work-life balance in academic medicine: narratives of physician-researchers and their mentors. J Gen Intern Med 2013;28:1596-603. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Edmunds LD, Ovseiko PV, Shepperd S, et al. Why do women choose or reject careers in academic medicine? A narrative review of empirical evidence. Lancet 2016;388:2948-58. [Crossref] [PubMed]