The prognosis of stage I non-small cell lung cancer with visceral pleural invasion and whole pleural adhesion after video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy: A single center retrospective study

Introduction

Surgery is the most effective treatment of early stage lung cancer. Since the development of minimally invasive surgery, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) is now the most commonly used procedure, and VATS lobectomy has become a standard surgical procedure for stage I non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). In terms of surgical outcomes, VATS lobectomy has a number of advantages over open thoracotomy (1); including less postoperative pain, shorter hospital stays, fewer complications and earlier functional recovery (2). Therefore, VATS lobectomy is currently performed for the treatment of lung cancer in most Korean hospitals.

According to the NCCN (National Comprehensive Cancer Network) guidelines, non-small cell lung cancer, version 3.2020, VATS should be strongly considered for NSCLC patients with no anatomic or surgical contraindications, provided the standard oncologic and dissection principles of thoracic surgery are not compromised. According to these guidelines, VATS should be performed when complete resection is possible. However in the case of severe pleural adhesion it is doubtful that complete resection can always be successfully performed. In the case of whole pleural adhesion, the operation time is long, the field of view is poor, and the tumor can be easily touched by surgical instruments, so there is a risk of potential tumor dissemination. In particular, in the case of whole pleural adhesions where the entire pleura and lung are attached, there may not even be a space where a thoracoscope can be inserted. While most surgeons can perform VATS lobectomy with pleural adhesiolysis to treat lung cancer, there has been little research done on the prognosis of lung cancer when VATS is performed in cases of severe whole pleural adhesion. Particularly in the case of peripheral lung cancer with visceral pleural invasion, it is questionable as to whether VATS is a safe operation.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate, in cases of stage I NSCLC treated by VATS, the prognostic effect of whole pleural adhesion when the tumor has undergone visceral pleural invasion. We set out to determine whether whole pleural adhesion is a risk factor for recurrence of tumor when performing VATS lobectomy for stage I NSCLC with visceral pleural invasion. We present the following article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jtd-20-1840).

Methods

Patients

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). This study was approved by the institutional review board of Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital at the Catholic University of Korea and individual consent was waived (Referral number: KC20RISI0343).

From January 2010 to December 2018, 1,994 consecutive patients underwent curative surgery for NSCLC at a tertiary hospital in Korea. Among them, 166 patients were diagnosed as stage I NSCLC with visceral pleural invasion and they underwent VATS lobectomy. Of these, we excluded 43 cases of partial pleural adhesion, leaving 123 consecutive patients to be reviewed retrospectively. We defined whole pleural adhesion as being where adhesion exists between the whole parietal pleura and visceral pleura; whereas partial pleural adhesion was defined as being where there was only partial adhesion between parietal pleura and visceral pleura. To reduce the selection bias, all data were obtained from consecutive patient data. The patients were divided into two groups; a whole pleural adhesion group, and a non-adhesion group. The clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis were compared between the two groups.

Clinical staging and surgical procedures

Patients diagnosed with clinical stage I lung cancer on the basis of chest computed tomography (CT) and positron emission tomography (PET)/CT scans, were deemed eligible for surgical treatment. As per ESTS (European Society of Thoracic Surgeons) guidelines, preoperative invasive nodal staging was not performed routinely on these patients because all tumors were peripheral and less than 3 cm in size (3).

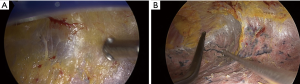

All patients underwent VATS lobectomy. VATS was performed by using one working incision and 2 or 3 thoracoscopic ports. In the case of whole pleural adhesion, a surgeon’s finger was placed into the working incision and blunt dissection undertaken to create a space. Then, the thoracoscope was put into the working incision (Figure 1A) and meticulous pleural adhesiolysis was conducted by electrocauterization using a curved instrument (Figure 1B).

The operation was undertaken by 2 surgeons. All surgeons were experts in thoracic surgery, with more than 20 years of experience in thoracic surgery. Operative procedures included anatomical lobectomy, and most patients also underwent systematic nodal dissection (SND) or lobe-specific nodal dissection (LSND). SND was defined as en bloc dissection of lymph node, with adjacent fat tissue, of more than 3 mediastinal lymph node stations and hilar lymph nodes. For patients with right-sided tumors, the paratracheal and subcarinal lymph nodes were routinely dissected; and for those with left-sided tumors, para-aortic, subaortic, and subcarinal lymph nodes were routinely dissected. LSND was defined as selective mediastinal lymph node dissection according to the lobar location of the primary tumor. For example, in the case of upper lobe tumor, only paratracheal or subaortic lymph nodes were dissected (4). N1 lymph nodes were dissected using the same method as for SND.

Histologic evaluation and pathologic staging

All clinical specimens and pathology reports were reviewed. Pathology reports included: histologic type, tumor size, tumor location, histologic tumor grade, visceral pleural invasion and lymphovascular invasion. Visceral pleural invasion was defined as tumor extending beyond the elastic layer. Lymphovascular invasion was defined as tumor cells present in lymphatic or vascular lumina. If the findings could not be determined using hematoxylin-eosin staining alone, special staining such as Verhoeff-Van Gieson elastic staining was performed as necessary. In particular, Verhoeff-Van Gieson elastic staining was performed for the detailed evaluation of visceral pleural invasion in those patients with visceral pleural invasion. TNM staging was based on the 8th edition of the TNM staging system of lung cancer (5). To determine the T category according to the 8th edition, tumor size was measured by the pathologist at the greatest diameter of the invasive component on a histopathological preparation (6).

Statistical analysis

Clinicopathological factors were compared using a Student t test or the Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables and chi-squared or Fisher exact test for categorical variables. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to analyze data collected from the interval between the time of operation and the time of the last follow-up visit. Recurrence-free survival (RFS) rates and disease-specific survival (DSS) rates were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method. Survival of each group was compared by log-rank test. A Cox proportional hazards model was used in a multivariate analysis to identify risk factors for recurrence after surgery. All variables with P<0.10 on univariate analysis were entered into the multivariate analysis. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 24.0 software (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, United States).

Results

Table 1 shows the comparison of clinicopathological characteristics between the whole pleural adhesion group and the non-adhesion group. There was no difference between two groups except in age; the whole pleural adhesion group was older than non-adhesion group (70.6 vs. 64.4 years, P=0.002).

Full table

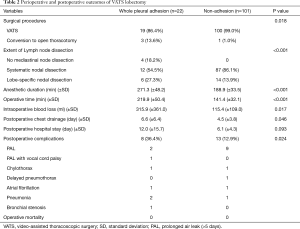

Table 2 shows the perioperative and postoperative outcomes. There were 3 cases of conversion to open thoracotomy in the whole pleural adhesion group and 1 case in the non-adhesion group (P=0.018). The conversions in the whole pleural adhesion group were all performed due to pleural adhesion, and in the non-adhesion group, it was because the lymph node was tightly attached to the blood vessel. The extent of lymph node dissection also differed between the two groups (P<0.001). In the non-adhesion group, mediastinal lymph node dissection was performed in all cases. However, mediastinal lymph node dissection was not performed in 4 patients (18.2%) in the whole pleural adhesion group, and SND was performed in only 12 patients (54.5%). In the whole pleural adhesion group, both anesthetic duration and operative times were longer (P<0.001, P<0.001, respectively). The volume of intraoperative blood loss was also higher in whole pleural adhesion group (P=0.017). The duration of postoperative chest drainage and postoperative hospital stay were longer in the whole pleural adhesion group (P=0.046, P=0.093, respectively). The complication rate was higher in whole pleural adhesion group than in the non-adhesion group (36.4% vs. 12.9%, P=0.024).

Full table

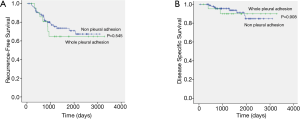

The median follow-up period was 1,330 days (range, 53 to 3,283 days). Two patients died within 1 year, not due to cancer-related causes. There were 7 recurrences in whole pleural adhesion group and 24 recurrences in the non-adhesion group. The distribution of the recurrence sites did not differ between the whole pleural adhesion group and the non-adhesion group (Table 3). The 5-year RFS rates for the whole pleural adhesion group and the non-adhesion group was not statistically different (64.8% and 70.9%, respectively, P=0.545) (Figure 2A). The 5-year DSS rates were also not statistically different in both groups (89.9% and 88.0%, respectively, P=0.908) (Figure 2B). Univariate and multivariate analysis of risk factors for recurrence in patients with stage I NSCLC with visceral pleural invasion after VATS lobectomy were conducted using the Cox proportional hazard model (Table 4). In the univariate analysis, the variables with P values less than 0.10 were: the maximum standardized uptake value of tumor on PET scan, the extent of lymph node dissection, adjuvant chemotherapy, histologic tumor grade, and lymphovascular invasion. Those variables with P values less than 0.10 were entered into the multivariate analysis. In the multivariate analysis, the extent of lymph node dissection (HR=13.854; P=0.023) was a significant risk factor for recurrence in patients with stage I NSCLC with visceral pleural invasion after VATS lobectomy. Whole pleural adhesion was not a risk factor for recurrence in this analysis.

Full table

Full table

Discussion

VATS, unlike open thoracotomy, has a narrow surgical field of view and use of the instrument is limited. However, the development of surgical techniques and of instruments has overcome these disadvantages and VATS lobectomy has now become a commonly performed operation (7,8). However, when we encounter a case of whole pleural adhesion with the entire lung and pleura attached, the limitations of VATS are still apparent. Nevertheless, because VATS has many advantages over open thoracotomy in terms of surgical outcomes, we perform surgery using VATS regardless of pleural adhesion (1,9). However, in the case of peripheral lung cancer with whole pleural adhesion, there is a risk of tumor rupture or tumor dissemination during VATS pleural adhesiolysis. There is concern about the oncological outcome of VATS lobectomy if the patient has whole pleural adhesion and visceral pleural invasion. In this study therefore, we evaluated the prognosis of stage I NSCLC with whole pleural adhesion and visceral pleural invasion, and found that the prognosis of the whole pleural adhesion group was not inferior to that of non-adhesion group.

In this study, we conducted a study on consecutive patients who had undergone lung cancer surgery in a hospital over an 8-year period and who met the inclusion criteria. The hospital, a tertiary hospital in Korea, performs over 250 lung cancer surgeries a year. All patients were consecutive patients, thus reducing the selection bias. Cases of partial pleural adhesion were excluded because the degree of partial adhesion in different patients was very diverse, making it impossible to objectively evaluate the effect of adhesion. As a result, only patients with stage I NSCLC with whole pleural adhesion and visceral pleural invasion were included in the study group, resulting in a relatively small total number of patients; that is, a whole pleural adhesion group (the study group) of 22 patients, and a non-adhesion group (the control group) of 101 patients. However, by conducting a study in a group of patients who had all undergone the same standardized type of surgery, the effect of pleural adhesion could be more accurately evaluated. Therefore, the results of this study, using data from patients who had undergone the same type of surgery, may be more accurate than those from a multi-center study in which various surgeries are applied by many surgeons.

Although the sample size of the whole pleural adhesion group was small in this study, the clinicopathological characteristics between the two groups were well matched, with only age differing; since the mean age of the whole pleural adhesion group was older than in the non-adhesion group. However, although the whole pleural adhesion group was older, the survival rate of the whole pleural adhesion group did not differ from the survival rate of the non-adhesion group. Therefore, even if there is visceral pleural invasion of the tumor, it seems that the effect of whole pleural adhesion on the prognosis following VATS lobectomy is minimal. The whole pleural adhesion group was older probably because these patients were more likely to have had a previous inflammatory disease of the lung.

Visceral pleural invasion has been considered an important prognostic factor for stage I NSCLC, and several previous studies have been undertaken of its prognostic effect (10,11). Even in the TNM staging system, visceral pleural invasion is a factor that may indicate a change in staging from IA to IB (12). In one study, pleural adhesion was shown to be a prognostic factor in stage I NSCLC (13). However, no studies to date have analyzed the risk of whole pleural adhesion in the presence of visceral pleural invasion. So, although our study has the disadvantage of having a small sample size, it is meaningful for this reason.

In our study, whole pleural adhesion was not found to be a risk factor for recurrence of NSCLC, whereas the extent of lymph node dissection was a risk factor for recurrence. In fact, systematic nodal dissection is often difficult to undertake successfully in cases of severe whole pleural adhesion. In addition, mediastinal node dissection, usually the last step in the surgical procedure, may not be performed as successfully as it could be, as the pleural adhesiolysis is a delicate and lengthy process and the concentration of the surgeon may gradually lapse. If the operation is prolonged and pleural adhesiolysis is required to be performed extensively, the amount of bleeding may gradually increase and the patient's condition becomes unstable. Therefore, lymph node dissection may at times be neglected. In this study, mediastinal lymph node dissection was omitted in 4 patients (18.2%) in the whole pleural adhesion group. On the other hand, in the non-adhesion group, all patients underwent mediastinal lymph node dissection. Although there was less lymph node dissection in the whole pleural adhesion group, the prognosis did not differ between the two groups. In other words, the presence of whole pleural adhesion did not affect prognosis in this study. The overall result of this study is that the extent of lymph node dissection is important in stage I NSCLC with visceral pleural invasion. Furthermore, systematic nodal dissection was a better prognostic factor than lobe-specific nodal dissection. It has been reported that clinical stage I NSCLC often undergoes nodal upstaging after surgery (14-18). In particular, in stage IB NSCLC with visceral pleural invasion, an increase in nodal upstaging may be more likely (14). Therefore, it is recommended that systematic nodal dissection should be performed in stage I NSCLC with visceral pleural invasion, even with whole pleural adhesion.

This study had several limitations that should be considered. Firstly, we used a retrospective study design. Secondly, we obtained data from a single institution with a relatively small sample size, so generalizing our results is difficult. However, the study patients were treated by a standardized surgical procedure at single institution. Furthermore, a detailed analysis was possible because of the detailed data contained in the electronic medical records. We also used detailed data from photos or videos of surgical procedures, pathological specimens and pathological reports. We believe that our data can be used as the basis for future investigations and that our results may be further clarified and refined by future studies with larger patient populations. Finally, the follow-up period was relatively short. However, recurrence of NSCLC is most commonly reported within a 2-year postoperative period (19), and early recurrence seems to be an accurate indicator of the long-term outcome (20).

In conclusion, whole pleural adhesion was found not to be a prognostic factor after VATS lobectomy in stage I NSCLC with visceral pleural invasion. Thus, even with whole pleural adhesion, VATS lobectomy may be safely performed in patients with lung cancer with visceral pleural invasion. In addition, the extent of lymph node dissection was identified as an independent prognostic factor in stage I NSCLC with visceral pleural invasion. Therefore, systematic nodal dissection is recommended when visceral pleural invasion is suspected, even if there is whole pleural adhesion. Further research using a larger pool of data may more accurately depict patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. 2019R1G1A1099670).

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jtd-20-1840

Data Sharing Statement: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jtd-20-1840

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jtd-20-1840). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). This study was approved by the institutional review board of Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital at the Catholic University of Korea and individual consent was waived (Referral number: KC20RISI0343).

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Whitson BA, Groth SS, Duval SJ, et al. Surgery for early-stage non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review of the video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery versus thoracotomy approaches to lobectomy. Ann Thorac Surg 2008;86:2008-16; discussion 2016-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Handy JR Jr, Asaph JW, Douville EC, et al. Does video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy for lung cancer provide improved functional outcomes compared with open lobectomy? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2010;37:451-5. [PubMed]

- De Leyn P, Dooms C, Kuzdzal J, et al. Revised ESTS guidelines for preoperative mediastinal lymph node staging for non-small-cell lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2014;45:787-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Adachi H, Sakamaki K, Nishii T, et al. Lobe-Specific Lymph Node Dissection as a Standard Procedure in Surgery for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Propensity Score Matching Study. J Thorac Oncol 2017;12:85-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goldstraw P, Chansky K, Crowley J, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: Proposals for Revision of the TNM Stage Groupings in the Forthcoming (Eighth) Edition of the TNM Classification for Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2016;11:39-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Travis WD, Asamura H, Bankier AA, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: Proposals for Coding T Categories for Subsolid Nodules and Assessment of Tumor Size in Part-Solid Tumors in the Forthcoming Eighth Edition of the TNM Classification of Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2016;11:1204-23.

- Sihoe AD. The evolution of minimally invasive thoracic surgery: implications for the practice of uniportal thoracoscopic surgery. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S604-17. [PubMed]

- Li Z, Li Y, Wang L, et al. Management of calcified hilar lymph nodes during thoracoscopic lobectomies: avoidance of conversions. J Thorac Dis 2019;11:657-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Whitson BA, Andrade RS, Boettcher A, et al. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery is more favorable than thoracotomy for resection of clinical stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 2007;83:1965-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jiwangga D, Cho S, Kim K, et al. Recurrence Pattern of Pathologic Stage I Lung Adenocarcinoma With Visceral Pleural Invasion. Ann Thorac Surg 2017;103:1126-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu QX, Deng XF, Zhou D, et al. Visceral pleural invasion impacts the prognosis of non-small cell lung cancer: A meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol 2016;42:1707-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rami-Porta R, Bolejack V, Crowley J, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: Proposals for the Revisions of the T Descriptors in the Forthcoming Eighth Edition of the TNM Classification for Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2015;10:990-1003.

- Nakada T, Noda Y, Kato D, et al. Risk factors and cancer recurrence associated with postoperative complications after thoracoscopic lobectomy for clinical stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Thorac Cancer 2019;10:1945-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dai J, Liu M, Yang Y, et al. Optimal Lymph Node Examination and Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Stage I Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2019;14:1277-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moon Y, Kim KS, Lee KY, et al. Clinicopathologic Factors Associated With Occult Lymph Node Metastasis in Patients With Clinically Diagnosed N0 Lung Adenocarcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg 2016;101:1928-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moon Y, Park JK, Lee KY, et al. Consolidation/Tumor Ratio on Chest Computed Tomography as Predictor of Postoperative Nodal Upstaging in Clinical T1N0 Lung Cancer. World J Surg 2018;42:2872-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Park JK, Moon Y. Prognosis of upstaged N1 and N2 disease after curative resection in patients with clinical N0 non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Dis 2019;11:1202-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Krantz SB, Lutfi W, Kuchta K, et al. Improved Lymph Node Staging in Early-Stage Lung Cancer in the National Cancer Database. Ann Thorac Surg 2017;104:1805-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tremblay L, Deslauriers J. What is the most practical, optimal, and cost effective method for performing follow-up after lung cancer surgery, and by whom should it be done? Thorac Surg Clin 2013;23:429-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kiankhooy A, Taylor MD, LaPar DJ, et al. Predictors of early recurrence for node-negative t1 to t2b non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 2014;98:1175-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]