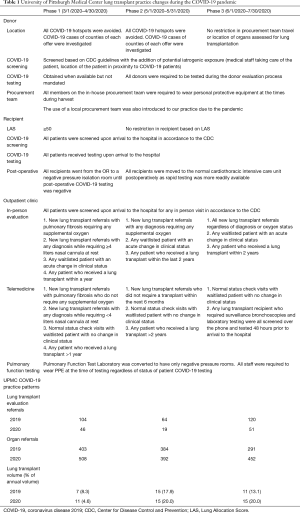

Lung transplantation protocols during the COVID-19 pandemic: a single center experience

The current global coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has left the medical field in an unprecedented public health emergency. While the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) recommended that solid organ transplantation not be postponed, many centers have halted or offered transplantation to only their sickest patients due to the uncertainty associated with donor to recipient transmission as well as the lack of universal and reliable access to donor COVID-19 testing in the early stages (1). The lung transplantation (LT) population is particularly vulnerable as the COVID-19 virus specifically targets the lungs and is associated with increased mortality in immunosuppressed and patients with significant comorbidities. Depending on the location of a center, each transplant program has been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic in a unique way in terms of local incidence, quality and availability of testing, and institutional and even statewide mandates at different timepoints of this year. However, due to the unforeseeable resolution, the lung transplant community had to adapt its practice to cautiously provide services to patients in need without compromising safety. In this article, we report our experience with lung transplantation during the COVID-19 pandemic in the mid-Atlantic region of the US.

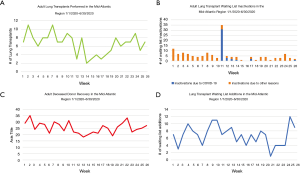

In the mid-Atlantic region where our center is located, the number of adult LTs performed between 1/1/2020–6/30/2020 drastically decreased by 21.4% when compared 2019, with an all-time low of 2–3 weekly transplants in April (Figure 1A) (2). This was directly correlated with the increase in waiting list inactivations (Figure 1B

Full table

Phase 1: the anticipation phase (3/1/2020–4/30/2020)

In order to adjust the approach to advanced lung diseases during the pandemic, we analyzed how the pandemic affected both our local healthcare system and our staff. Based on Holm and colleagues, we found ourselves to be in the Anticipation stage during March and April of this year (3). While the first COVID-19 cases reported in the US were in January, we experienced only a minimal number of cases locally. Therefore, our LT team met in early March 2020 and implemented a series of protective measures.

Initial donor and recipient restrictions

Due to COVID-19’s high virulence, all staff and visitors involved with both LT donors and recipients were required to wear personal protective equipment (PPE) consisting of masks, gowns and gloves, including our procurement team regardless to travel to low or high incidence areas. Because there was not universal donor testing during this time, our initial decision was to transplant patients with a Lung Allocation Score (LAS) ≥50. The ideal donor scenario was to have a negative COVID-19 test during donor evaluation with the standard information. If testing was not available, donors were evaluated for possible exposure such as geographic location in a COVID-19 hotspot as defined by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (4), history of travel to a hotspot within 14 days of death, and any potential iatrogenic exposure with physical proximity to a hospital’s COVID-19 patients/ward. Determination of a county’s hotspot status was defined utilizing the CDC reporting of the COVID-19 cases (5). At the time of the lung offer, patient’s physical proximity to the hospital’s COVID-19 patients/ward was obtained by interviewing the organ procurement organization (OPO). If the testing or history indicated COVID-19 exposure, offers were declined regardless of quality and recipient acuity. In the event of lack of access to COVID-19 testing, if a donor was deemed low risk and the offer was accepted, once the LT implant was complete, recipients underwent a final bronchoscopy for evaluation and pulmonary toilet. A bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was obtained and sent for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for COVID-19. Initially, because these tests took several hours to finalize, recipients were transported immediately following surgery into an intensive care unit negative pressure room as they waited for a negative test result before being released to the standard CT-ICU locations with the goal of minimize staff and other patient exposure. This practice implemented but scarcely used as only a handful few patients were moved to negative pressure rooms immediately postoperative until our in-house as well as donor hospital COVID-19 testing became more reliable.

Initial outpatient pre-transplant evaluation, waiting list, and long-term follow-up visits

We relied on telemedicine for all initial LT evaluations, wait list re-evaluations, and follow up outpatient visits. All patients invited for outpatient clinic visits were screened in accordance to the CDC guidelines (6). Initial in-person clinic evaluations were reserved for patients with pulmonary fibrosis requiring supplemental oxygen, patients with any diagnosis requiring ≥4 liters nasal cannula at rest, waitlisted patients with an acute change in clinical status, and all post-transplant patients who received a LT within a year. All remaining patients received outpatient follow-up virtually. Due to the challenges in performing pulmonary function tests at other institutions, patients received home micro-spirometers for continual functional monitoring in the setting of limited access to the pulmonary function testing (PFT) laboratory (Monitored Therapeutics Incorporated GoSpiro Home Spirometer, Dublin, Ohio, USA). Rooms in our hospital PFT laboratory were converted to negative pressure rooms and respiratory staff were required to wear PPE during all tests.

Phase 2: regrouping (5/1/2020–5/31/2020)

Our first donor experience during this phase was an offer to a patient with dermatomyositis and a LAS score of 92.5. Even with pre-formed HLA antibodies, he was offered a set of lungs that were a great size and quality match 10 days after listing. Because this was an out of state offer, we investigated the prevalence of COVID-19 in the region that the donor was located. There were only 38 COVID-19+ cases in the county where the donor was located. Our excitement was met with some anxiety as the donor was situated in the same unit as a COVID-19+ patient and shared the same clinical care team. Therefore, we held a multidisciplinary meeting to fully weigh the risks and benefits. With our colleagues from pulmonary medicine and infectious disease, we discussed a case-by-case basis on the potential COVID-19 exposure in each donor instance as well as the clinical acuity of our recipient and clinical factors that may impede their chances at another suitable pair of lungs. We decided to proceed and our team procured the lungs safely due to the patient’s high acuity and a negative crossmatch in the setting of an extensive reactive antibody profile. Once transplanted, the recipient was transported to a negative pressure room for 24 hours until the COVID-19 testing via BAL at our institution was negative. The patient has now been discharged and is doing well.

Re-evaluation of donor and recipient programmatic changes

As COVID-19 testing became more readily available, we began phase 2 by removing our LAS restriction on our transplant waitlist. All recipients received rapid COVID-19 testing once they arrived at the hospital with results in 1–3 hours. Virtually all donor offers included COVID-19 testing and we experienced no pushback either from the donor hospitals or the hosting OPOs. Because of these improvements, while we still avoided donors from COVID-19 hot-spot areas, we were more liberal with donors located in non-isolated units or that shared same clinical care team or were located in a higher incidence region. We continued to scrutinize donor exposure history including high-risk travel based on COVID-19 incidence. While we liberated our donor restrictions and allowed for use of COVID-19 negative lungs procured from areas with a high incidence of COVID-19 infections, we were still careful on maintaining the safety of our procurement team. Therefore, in order to minimize their exposure to COVID-19, we also utilized local procurement teams in 2 out of 15 procurements in the month of May when the location of the donor hospital was located in areas with a high incidence of COVID-19 infections.

Re-evaluation of outpatient pre-transplant evaluation, waiting list, and follow-up visits

Due to the low COVID-19 incidence locally, our outpatient service restrictions were also loosened. After completing the first 11 transplants during the anticipation phase, we continued the use of telemedicine for low acuity LT referrals who presumably would not require a transplant within 6 months and any post-lung transplant patient >2 years from transplantation. However, in the setting of a waiting list consisting of roughly 20 patients, we broadened the in-person outpatient clinic new evaluations to any patient who required supplemental oxygen at rest. In-person post-transplant maintenance visits with PFTs, chest radiography, surveillance bronchoscopy, and laboratory testing were performed to any recipient who had their surgery within the last two years. We received much needed support from other outpatient laboratory test sites as they provided low-traffic time slots for our immunosuppressed patients.

Phase 3: looking towards the future (6/1/2020–7/30/2020)

By June, most OPOs and hospitals we traveled to for donor procurements were capable of performing timely COVID-19 testing. Therefore, we liberated travel restrictions and began accepting organs from hot-spot areas where the incidence was still relatively high and continued to utilize local procurement teams when possible to minimize exposure for our staff. We maintained the practice of screening and testing all recipients when they arrived at the hospital.

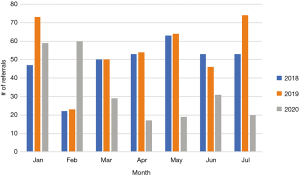

In the midst of the pandemic, since March, we recognized that our LT evaluation referrals have decreased significantly in comparison to the two previous years (Figure 2). In an effort to build our waiting list, all referrals were seen in person after assessing COVID-19 risk. While some routine wellness clinic visits were performed via telemedicine, all patients who required a bronchoscopy for surveillance or for any clinical suspicion were all screened for COVID-19 over the phone and tested 48 hours prior to their visit at partner clinics and hospitals.

Programmatic limitations

Due to the level of uncertainty we were working under, we implemented a set of stopping rules for our lung transplant program. These rules were defined to recognize events that could prevent us to continue performing transplantation in a safe manner. Our first stopping rule was the use of mechanical ventilators and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) circuits at 75% of hospital capacity. The second stopping rule was if the number of COVID-19 patients requiring ECMO support exceeded 10 as this was the number of negative pressure rooms available in our CT-ICU.

While careful programmatic reflection is necessary, we believe the current pandemic does not require a complete halt of all lung transplantation as non-action can also equate the harm for lack of appropriate care to our sickest patients. Ultimately, each lung transplant program will need to assess the impact that COVID-19 has upon their institution resources.

Acknowledgments

We would like to take this time to especially acknowledge our UNOS Data & ORC Manager Roy R. Hill for participating in the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was a standard submission to the journal. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jtd-20-3289). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- CMS Releases Recommendations on Adult Elective Surgeries, Non-Essential Medical, Surgical, and Dental Procedures During COVID-19 Response. 2020. Available online: https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-releases-recommendations-adult-elective-surgeries-non-essential-medical-surgical-and-dental. Accessed July 31, 2020.

- United Network for Organ Sharing: Current state of organ donation and transplantation. 2020. Available online: https://unos.org/covid/. Accessed July 22, 2020.

- Holm AM, Mehra MR, Courtwright A, et al. Ethical considerations regarding heart and lung transplantation and mechanical circulatory support during the COVID-19 pandemic: an ISHLT COVID-19 Task Force statement. J Heart Lung Transplant 2020;39:619-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oster AM, Kang GJ, Cha AE, et al. Trends in Number and Distribution of COVID-19 Hotspot Counties - United States, March 8-July 15, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1127-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention: Coronavirus (COVID-19). 2020. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/. Accessed October 4, 2020.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention: COVID-19 Active Screening Questionnaire. 2020. Available online: https://www.doc.wa.gov/news/2020/docs/2020-0330-active-screening-questionnaire.pdf. Accessed July, 10, 2020.