Beating-heart on-pump coronary artery bypass grafting vs. off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Introduction

Coronary artery disease is a common condition that seriously endangers human health. In recent years, there has been an increasing application of percutaneous myocardial revascularization in managing this disease. To date, conventional on-pump coronary artery bypass grafting (C-ONCAB) remains the gold standard for surgical coronary artery revascularization (1). However, this established technique is often associated with adverse effects such as systemic inflammation, neurological dysfunction, renal dysfunction, and other postoperative complications (2). The application of cardiopulmonary bypass (CBP) and cardioplegic arrest is significant triggers for these adverse perioperative events. Off-pump CABG (OPCAB) is an alternative technology that avoids the use of CPB, aortic cross-clamping, and cardioplegic arrest, and may reduce the incidences of adverse events, especially in high-risk and elderly patients. However, other adverse events have been associated with OPCAB. According to the Randomized On/Off Bypass (ROOBY) trial, OPCAB was associated with a higher rate of incomplete revascularization and an inferior long-term outcome (3).

In the mid-1990s, beating-heart on-pump CABG (BH-ONCAB) was firstly introduced for clinical application. This technique combines the advantages of OPCAB and conventional CABG. Theoretically, BH-ONCAB would cause less myocardial injury by preserving native coronary blood flow while maintaining hemodynamic stability with effective support from CPB (4). It may also provide higher perfusion pressure and avoid aortic cross-clamping, which may lead to less stroke, renal dysfunction, and perioperative myocardial ischemia, all of which are particularly beneficial for high-risk group patients (5).

There have been abundant studies comparing OPCAB and C-ONCAB, but there is a paucity of data on BH-ONCAB. This meta-analysis assessed the clinic outcomes of BH-ONCAB compared with OPCAB in the short- and long-term postoperative period.

We present the following article in accordance with the PRISMA reporting checklist (available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jtd-21-268).

Methods

Literature search

A literature search was performed in the Cochrane Central, MEDLINE (PubMed), Web of Science, EMBASE (OVID Interface), and CNKI databases using the key terms, “cardiopulmonary bypass”, “coronary artery bypass”, “beating heart”, and “off the pump”, either alone or in combination. Studies published with an abstract between 1990 and 1st August 2020 were considered. There were no limitations on the language of publication. A summary of the literature selection strategy is described in Figure 1.

Selection criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (I) direct comparison of BH-ONCAB vs. conventional OPCAB; and (II) the study provided at least one of the following major clinical outcomes: early mortality, long-term survival, myocardial infarction, low output symptoms, the incidence of incomplete revascularization, and renal dysfunction.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (I) use of concomitant interventions; (II) use of miniaturized CPB or other modifications of OPCAB vs. BH-ONCAB; (III) data inconsistencies prohibiting valid data extraction; and (IV) studies that contained duplicate data, in which case the more credible and recently published data set was selected.

Literature with a Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS) score of 6 or higher were regarded as high-quality studies. Two reviewers used the selection criteria to assess all eligible articles based on title, and abstract review, followed by a full-text article review, and the final selection was determined. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion and/or arbitration with a senior author.

Data collection

The investigators independently extracted data from each study using a standardized spreadsheet based on publication year, first author, place of study, study design, period of patient enrollment, number of participants treated with OPCAB and BH-ONCAB, study population, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and outcome measures.

Study variables

The primary outcome measure was the early mortality rate in hospitals and the long-term survival rate after surgery. The secondary outcomes were major postoperative complications, including myocardial infarction, low output syndrome, stroke, dialysis, arrhythmias, intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) use, inotrope use, incomplete revascularization and renal dysfunction.

Quality scoring

Two reviewers used the Jadad composite scale to assess the quality of the randomized controlled trial (RCTs) (6), and the modified Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale Score (NOS) was used to assess the quality of observational studies (7). Studies with a Jadad score of no less than 2 (maximum score 5) or a modified NOS score of no less than 5 (maximum score 9) were considered high-quality studies.

Risk of bias analysis

According to the Cochrane guidelines, the risk of bias was evaluated (Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0). Two authors reviewed all the studies, marking “yes”, “no”, or “unclear” to the following parts: (I) allocation concealment (selection bias); (II) random sequence generation (selection bias); (III) blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias); (IV) blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias); (V) selective reporting (reporting bias); (VI) incomplete outcomes data (attrition bias); and (VII) other bias.

Statistical analysis

This meta-analysis used a weighted fixed effects model to analyze the data. For primary outcomes, the odds ratio (OR) and the logarithm of the hazard ratio (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to calculate survival differences. For secondary outcomes, categorical variables were assessed by the OR, and an OR of less than 1 would favor the treatment group. The point estimate of the OR would be considered statistically significant if the P value was less than 0.05 and the 95% CI did not equal the value of 1. Continuous data were analyzed by the weighted mean difference (WMD) as the summary statistic with the 95% CI, and the point estimate of the WMD was considered statistically significant if p was less than 0.05 and the 95% CI interval did not equal to the value 0. The Q-statistic and I2 (index of inconsistency) tests were used to quantify the degree of heterogeneity in all studies. If statistically significant heterogeneity (P<0.1 or I2>50%) was detected in the included studies, random effects models were used for pooled analysis, and sensitivity analyses were performed to identify the source of heterogeneity. Sensitivity analyses were performed by omitting each study in sequence. Publication bias was assessed by visual inspection of funnel plots. Data were analyzed with the RevMan 5.3 software (The Nordic Cochrane Center, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark).

Results

Literature search

A total of 22 articles were identified in the initial search, and 4 were excluded based on the selection criteria, including 2 articles with duplicate data and 2 studies that focused on mini-CPB with little comparative data. Finally, a total of 18 single-center studies (8-25) were enrolled in this meta-analysis, including a total of 5,615 patients, of which 1,548 had undergone BH-ONCAB, and 4,067 were treated with OPCAB. There were 5 RCTs (9,10,12,14,22), and 13 retrospective observational studies (8,11,13,15-21,23-25). A summary of the basic characteristics of the 18 included studies is presented in Table 1.

Full table

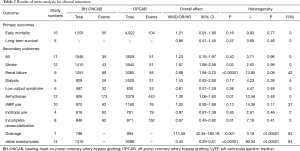

Early mortality

Early mortality was defined as death occurring within 30 days after surgery or in-hospital death at any time. 17 of all 18 studies (8-25) provided information on early mortality (Table 2, Figure 2). Analysis of 18 included studies demonstrated that there were no differences in the overall early mortality between BH-ONCAB and OPCAB patients (OR 1.28; 95% CI: 0.91 to 1.80; Z=1.40, P=0.16), and there was no significant heterogeneity (I2=0; Figure 2A).

Full table

Long-term survival

Data for long-term survival were available for 5 studies (15,18,21,23,24), and no significant differences were found in overall survival between the two groups (HR 0.86; 95% CI: 0.51 to 1.45; Z=0.57, P=0.57). There was no significant heterogeneity (I2=0; Figure 2B; Table 2).

Secondary outcomes

A synopsis of the secondary endpoints is shown in Table 2 and Figure 2.

A total of 12 studies (8,11,13,15-19,21,23-25) were included in the analysis of postoperative stroke. The summary OR suggested that patients treated with BH-ONCAB had a higher incidence of postoperative stroke (OR 1.67; 95% CI: 1.08 to 2.58; Z=2.32, P=0.02), with no significant heterogeneity (I2=0; Figure 2B).

Data for postoperative renal failure was available for 9 studies (8,11,13,15-17,21,23,25). However, there was significant heterogeneity among the studies (I2 = 42%, P=0.09). Heterogeneity (I2=6%; P=0.38) was acceptable after removing the study by Edgerton et al. (15), and exclusion of this study did not influence the overall results.

Data from 13 studies were used for analysis of postoperative arrhythmias (8,10,12-15,17-19,21,23-25). The heterogeneity (I2=45%, P=0.04) is significant and the removal of the study by Velioglu et al. (25) makes the heterogeneity acceptable (I2=0%, P=0.48). The total OR suggested that OPCAB patients were less likely to have arrythmias compared to BH-ONCAB patients (OR 1.30; 95% CI: 1.06 to 1.60; Z=2.47, P=0.01).

The total OR for the incidence of incomplete revascularization (8,10,11,13,21,22,24,25) suggested that BH-ONCAB patients were less likely to experience incomplete revascularization compared to OPCAB patients (OR, 0.67; 95% CI: 0.49 to 0.92; Z=2.49, P=0.01), with no significant heterogeneity (I2=0, P=0.53).

Analysis of 8 studies (8,13,14,16,20,21,24,25)revealed that BH-ONCAB patients experienced more blood loss compared to OPCAB patients (8,13,14,16,20,21,24,25) (MD 111.56; 95% CI: 42.94 to 180.18; Z=3.19, P=0.001).

Fourteen studies (8-15,17,20,21,23-25) provided details related to distal anastomoses and showed that OPCAB patients had significantly less distal anastomoses compared to BH-ONCAB patients (MD 0.45; 95% CI: 0.29 to 0.61; Z=5.51; P<0.00001; studies (8-15,17,20,21,23-25).

No differences were observed for the other postoperative events including myocardial infarction (8,10,12,13,15-19,21,23) (OR 1.23, 95% CI: 0.76 to 1.97; Z=0.85, P=0.40), dialysis (11,13,15,23,25) (OR 1.53; 95% CI: 0.83 to 2.80; Z=1.37, P=0.17), low output syndrome (13,16,17,23-25) (OR 0.81; 95% CI: 0.51 to 1.28; Z=0.91, P=0.36), IABP use (8,11-13,15,16,21-25) (OR 1.32; 95% CI: 0.92 to 1.88; Z=1.51, P=0.13; removal of the study by Edgerton et al. (15) due to the higher heterogeneity), and inotropic use (8,13,19,21,25) (OR 0.97; 95% CI: 0.67 to 1.39; Z=0.19, P=0.85, removal of the study by Darwazah et al. (8) due to the higher heterogeneity).

Discussion

This meta-analysis compared the clinical outcomes between BH-ONCAB and OPCAB in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery. The results demonstrated comparable early mortality and long-term survival between BH-ONCAB and OPCAB coronary revascularization with no significant statistical differences. No heterogeneity was observed when analyzing the early mortality and long-term survival. Furthermore, advantages observed in BH-ONCAB patients included lower incidences of incomplete revascularization and greater numbers of distal anastomoses. However, BH-ONCAB patients experienced an increased risk of stroke, renal failure, arrhythmia, and drainage.

To date, conventional ON-CABG is still the gold standard for surgical coronary artery revascularization. However, it has been associated with severe postoperative complications due to the use of cardiac, pulmonary bypass. In the 1990s, OPCAB was developed to be used without cardioplegia, aortic cross-clamping, or hypothermia to avoid adverse events such as systematic inflammation and renal failure (26). Previous studies have demonstrated that compared with conventional CABG, OPCAB showed decreased morbidity and mortality and is favorable for severe coronary disease patients, especially for those with contraindications for CPB (27,28). However, despite those advantages, OPCAB still has inherent defects compared with conventional CABG, such as incomplete revascularization and inferior long-term graft patency (3). In addition, one of the most severe problems is that OPCAB sometimes requires emergent conversion to conventional CABG in certain high-risk patients with unstable hemodynamics, which might lead to high morbidity and mortality (29). Thus, BH-ONCAB has been developed to overcome these issues. BH-ONCAB allows coronary artery flow during surgery, thereby eliminating the cross-clamping of the aorta and reducing the time of CBP. It is safe and suitable for the most unwell and unstable patients (15). This current analysis demonstrated that early mortality and long-term survival of BH-ONCAB patients was similar to that of OPCAB patients, which suggested that short-term cardiopulmonary bypass without avoiding cardiac arrest and aortic clamping did not increase the mortality of BH-ONCAB patients.

Although the CPB time for cardiac manipulation is limited in BH-ONCAB, the CPB support itself still led to some complications. This might account for the higher rate of certain postoperative complications in BH-ONCAB patients, such as renal failure, stroke, arrhythmia, and increased drainage or blood loss compared to OPCAB patients. Thus, non-CPB techniques may be better suited to patients at high risk for those complications instead of BH-ONCAB, which may aggravate the condition. However, patients with cardiac dysfunction usually cannot tolerate prolonged intraoperative maneuvers and position shifts with non-CPB-support heart beating. The support of CPB could provide a better surgical visual field and allow the surgeon to operate more efficiently in BH-ONCAB surgery. This may explain the improved revascularization and greater number of distal anastomoses in BH-ONCAB patients. In conclusion, the BH-ONCAB technique may provide more efficient hemodynamic support than OPCAB while reducing the side effects of conventional CABG with shortened CPB time.

The risk of myocardial infarction in BH-ONCAB patients was similar to that of OPCAB patients. The reasons for this remain unclear but may be affected by multiple factors, such as myocardial ischemia caused by CPB and improved revascularization. Future investigations with a larger cohort are required to understand further the mechanisms involved.

There were several limitations in this research. This meta-analysis compared BH-ONCAB with OPCAB, including 18 studies and 5,615 patients. Only 5 of these 18 studies were RCTs. The other 13 studies were small observational studies, and it may have been difficult to accumulate data prospectively, and there may be a high level of selection bias. Furthermore, some outcomes had a small number of events, leading to a higher risk of Type I error. Finally, the period of the included studies was 19 years, and the results may not reflect the improvements in surgical techniques over that period.

Conclusions

In conclusion, BH-ONCAB and OPCAB were comparable in terms of early mortality and long-term survival. However, each technique had its pros and cons regarding the risk of secondary outcomes. BH-ONCAB was associated with fewer incidences of incomplete revascularization and more distal anastomoses, while OPCAB was associated with a lower risk of stroke, renal failure, arrhythmia, and drainage. There were no statistically significant differences in the incidences of myocardial infarction and low output syndrome. Future work should focus on larger matched studies and multicenter randomized controlled trials, and this will allow us to further optimize our surgical revascularization strategies in these patients.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted in the Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology. We are grateful to Dr. Li and Dr. Yin for their generous assistance.

Funding: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (2016YFA0101100, 81873503).

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the PRISMA reporting checklist. Available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jtd-21-268

Peer Review File: Available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jtd-21-268

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jtd-21-268). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Anyanwu AC, Adams DH. Total Arterial Revascularization for Coronary Artery Bypass: A Gold Standard Searching for Evidence and Application. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72:1341-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hillis LD, Smith PK, Anderson JL, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA Guideline for Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2011;124:e652-735. [PubMed]

- Shroyer AL, Grover FL, Hattler B, et al. On-pump vs. off-pump coronary-artery bypass surgery. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1827-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Perrault LP, Menasche P, Peynet J, et al. On-pump, beating-heart coronary artery operations in high-risk patients: an acceptable trade-off? Ann Thorac Surg 1997;64:1368-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Quan XQ, Cheng ZY, Sun JJ, et al. Effects of on-pump beating-heart coronary artery bypass grafting for left-main patients. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2013;93:2545-8. [PubMed]

- Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials 1996;17:1-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- GA Wells, B Shea, D O'Connell, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Available online: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

- Darwazah AK, Bader V, Isleem I, et al. Myocardial revascularization using on-pump beating heart among patients with left ventricular dysfunction. J Cardiothorac Surg 2010;5:109. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jalal A, Yunus A, Abualazm AM, et al. Coronary artery bypass grafting on beating heart. Does it provide superior myocardial preservation than conventional technique? Saudi Med J 2007;28:848-54. [PubMed]

- Rastan AJ, Bittner HB, Gummert JF, et al. On-pump beating heart vs. off-pump coronary artery bypass surgery-evidence of pump-induced myocardial injury. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2005;27:1057-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lin CC, Wu MY, Tsai FC, et al. Prediction of major complications after isolated coronary artery bypass grafting: the CGMH experience. Chang Gung Med J 2010;33:370-9. [PubMed]

- Lin CY, Yang TL, Hong GJ, et al. Enhanced intracellular heat shock protein 70 expression of leukocytes and serum interleukins release: comparison of on-pump and off-pump coronary artery surgery. World J Surg 2010;34:675-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Munos E, Calderon J, Pillois X, et al. Beating-heart coronary artery bypass surgery with the help of mini extracorporeal circulation for very high-risk patients. Perfusion 2011;26:123-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wan IY, Arifi AA, Wan S, et al. Beating heart revascularization with or without cardiopulmonary bypass: evaluation of inflammatory response in a prospective randomized study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2004;127:1624-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Edgerton JR, Herbert MA, Jones KK, et al. On-Pump Beating Heart Surgery Offers an Alternative for Unstable Patients Undergoing Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting. Heart Surg Forum 2004;7:8-15. [PubMed]

- Shen JQ, Ji Q, Ding WJ, et al. Myocardial revascularization among patients with severe left ventricular dysfunction: a comparison between on-pump beating-heart and off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi 2018;56:294-8. [PubMed]

- Kim KB, Lim C, Lee C, et al. Off-pump coronary artery bypass may decrease the patency of saphenous vein grafts. Ann Thorac Surg 2001;72:S1033-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Skancke M, Endicott K, Amdur R, et al. Outcomes of beating heart on pump utilizing a miniature bypass circuit vs. off-pump cardiac bypass at a Veterans Affairs Medical Center. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2018;59:268-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Miguel SU, Vanessa R, Nuno M, et al. Cirurgia Coronária:Cirurgia Coronária:Que Método Utilizar? Rev Port Cardiol 2003;23:517-30.

- Sabban MA, Jalal A, Bakir BM, et al. Comparison of neurological outcomes in patients undergoing conventional coronary artery bypass grafting, on-pump beating heart coronary bypass, and off-pump coronary bypass. Neurosciences (Riyadh) 2007;12:35-41. [PubMed]

- Gurbuz O, Kumtepe G, Yolgosteren A, et al. A comparison of off- and on-pump beating-heart coronary artery bypass surgery on long-term cardiovascular events. Cardiovasc J Afr 2017;28:30-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mizuno T, Egi K, Sakai K, et al. Minimally Circulatory-Assisted On-Pump Beating Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting for Patients With Complex Conditions for Off-Pump Surgery. Artif Organs 2017;41:233-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang W, Wang Y, Piao H, et al. Early and Medium Outcomes of On-Pump Beating-Heart vs. Off-Pump CABG in Patients with Moderate Left Ventricular Dysfunction. Braz J Cardiovasc Surg 2019;34:62-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tsai YT, Lin FY, Lai CH, et al. On-pump beating-heart coronary artery bypass provides efficacious short- and long-term outcomes in hemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012;27:2059-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Velioglu Y, Isik M. Early-Term Outcomes of Off-Pump vs. On-Pump Beating-Heart Coronary Artery Bypass Surgery. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2019;67:546-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Murphy GJ, Ascione R, Angelini GD. Coronary artery bypass grafting on the beating heart: surgical revascularization for the next decade? Eur Heart J 2004;25:2077-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hijazi EM. Is it time to adopt beating-heart coronary artery bypass grafting? A review of literature. Rev Bras Cir Cardiovasc 2010;25:393-402. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ueki C, Sakaguchi G, Akimoto T, et al. On-pump beating-heart technique is associated with lower morbidity and mortality following coronary artery bypass grafting: a meta-analysis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2016;50:813-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee D, Ashrafian H, Kourliouros A, et al. Intra-operative conversion is a cause of masked mortality in off-pump coronary artery bypass: a meta-analysis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2012;41:291-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

(English Language Editors: J. Teoh and J. Chapnick)