Social determinants of health among family caregiver centered outcomes in lung cancer: a systematic review

Highlight box

Key findings

• Current studies provide evidence of the critical role of social determinants of health (SDOH) factors on lung cancer family caregivers’ (FCGs) quality of life.

• The studies included in this review largely focused on three out of the five SDOH domains: social and community context, healthcare access and quality and economic stability.

• Tools used to measure SDOH factors lacked standardization and primarily focused on demographic variables.

What is known and what is new?

• SDOH is an understudied topic in lung cancer research for FCGs.

• SDOH factors influence the overall quality of life of FCGs including their psychological well-being, relationship quality, and increased economic hardship.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• SDOH factors significantly influence QOL of FCGs, and utilization of validated measures across all five domains would provide greater data consistency that could inform interventions to improve their health outcomes.

Introduction

Cancer continues to be a growing health concern throughout the world. Historically, lung cancer has been one of the most disparate malignancies in the United States (1), with high levels of symptom burden and quality of life (QOL) needs that are challenging for both the patients and their family caregivers (FCGs) (2). FCGs are relatives or friends who assume care responsibilities for a patient (3). How a patient and their FCGs adapt to a lung cancer diagnosis and their ability to access quality and timely lung cancer care are influenced by an array of non-disease and non-clinical factors. These factors are referred to as social determinants of health (SDOH). The US Department of Health Human Services defines SDOH as the social and physical environmental conditions in which people live, work, age, play, and pray (4). The SDOH framework (Figure 1) includes five broad domains: economic stability, education access and quality, neighborhood and built environment, healthcare access and quality, and social and community context (5,6). The effects of SDOH on health outcomes can be disadvantageous (7,8). Compared to individuals living in higher socioeconomic status (SES) neighborhoods, individuals residing in lower SES neighborhoods have higher rates of morbidity and mortality from many diseases (9-11), including lung cancer (12-14). Similarly, studies have shown associations between low education, living in racially segregated neighborhoods, low social support and mortality for myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular disease, and lung cancer (15,16). Patients with cancer and FCGs often experience significant out of pocket costs and employment disruptions, resulting in financial toxicity (17). Other social conditions such as SES, behavioral needs, and environmental circumstances may impact QOL outcomes among patients with lung cancer (18).

Research on SDOH for FCGs has mainly focused on pediatric populations (19-21) and chronic conditions (22,23). Furthermore, studies have largely focused on three out of the five SDOH domains, with economic stability, social and community context, and healthcare access [including health literacy (24)] and quality dominating the literature (19). Other important domains, including education access and quality and neighborhood and built environment, are often not prioritized, or assessed. Another important yet understudied sub-factor within the social and community context domain is spirituality, which is defined as the belief in something greater than oneself, and guidance of that belief in understanding connections to self, others, nature, and the sacred (25-27). Spirituality has been found to encourage social cohesion, defined as the cooperative achievement of goals among individuals in a community that contributes to progressive health and economic outcomes (28,29).

While lung cancer incidence has been found to be associated with SDOH factors such as education, occupation, and income (30), our understanding of other SDOH domains on lung cancer FCG outcomes is limited. Although SDOH accounts for nearly 80% of an individual’s health status (31), the literature is sparse regarding SDOH in relation to cancer caregiving, specifically in the context of lung cancer. Questions remain in understanding the relationships between SDOH and lung cancer outcomes for FCGs. Within this framework, a systematic review was conducted to determine the current state of the literature on SDOH for FCG-centered outcomes in lung cancer. We present this article in accordance with the PRISMA reporting checklist (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-22-1613/rc) (32).

Methods

Search strategy

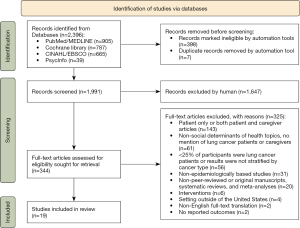

The authors (DT, VS, JK) developed search strategy criteria with the assistance of a librarian using the following databases: PubMed/MEDLINE (Legacy version); Cochrane Library; Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) Plus with Full Text; and American Psychological Association (APA) PsycInfo. The following search terms were used: lung cancer, family caregivers, patients, and social determinants of health. The keywords were combined with synonyms, alternate spellings/word endings, and controlled vocabulary, such as Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), to retrieve relevant results. Social determinants of health factors were broken down into individual keywords such as education, economic status, healthcare disparities, etcetera. The complete list of search strategies, including MeSH terms, can be found in Appendix 1. The librarian performed all searches, with inputs from three authors (DT, VS, JK). This search strategy yielded 2,396 articles. The search results were further filtered limiting inclusion to studies published in the last ten years (January 2010-December 2020), human participants, and English language studies. For PubMed/MEDLINE, we also filtered the articles by (I) age: all Adults; (II) publication types (refer to Appendix 1 for specifics). CINAHL results were limited to the Age Group “All Adult” and peer reviewed publications. After applying these criteria, the search strategy yielded 1991 sources after removing duplicate records (n=7).

Eligibility criteria

We included peer-reviewed original manuscripts published between 2010–2020, if at least 25% of participants were adult family caregivers of lung cancer patients. Exclusion criteria eliminated studies that were published prior to 2010, non-English studies, not conducted in the United States, dissertations, and other non-peer reviewed manuscripts. Due to the complexity of SDOH and lung cancer outcomes among FCGs, we chose to limit the scope of this review to the United States. We also excluded studies with the following designs and/or topics: interventions, systematic literature reviews/meta-analyses, case studies, drug efficacy trials, lung cancer screening, and basic science studies.

Data abstraction

We performed title/abstract screening, full-text screening, and data abstraction using the Covidence systematic review software tool (33). DT, ML, ME, MC, VS, JK and BF participated in the title/abstract screening, full-text screening, and data abstraction. Disputes over inclusion were resolved via virtual face to face discussions between DT, VS, and JK until consensus was reached. Of the 1,991 titles/abstracts screened, we excluded 1,647. Three-hundred forty-four articles remained for full-text evaluation. Figure 2 illustrates the review process for final studies included in our qualitative synthesis. We then used the inclusion criteria to evaluate full-text articles and excluded an additional 338 studies. Using Covidence Extraction 2.0 template developed by DT in consultation with VS and JK, we abstracted the following information from each article selected for this review: (I) first author’s last name; (II) publication year; (III) study design; (IV) stage of disease; (V) treatment type; (VI) family caregiver demographic information (age, race/ethnicity, income, education level, setting); (VII) primary SDOH domain assignment; (VIII) secondary SDOH domain assignment; (IX) if SDOH domain selected was Social & Community context, was spirituality included; (X) if SDOH variables were connected to the outcome of the study or QOL of FCGs; (XI) type of validated SDOH tool used in data collection. DT, VS, and JK discussed assignments until consensus on domains was reached. For articles with a primary and secondary domain assignment, the primary domain assignments were included in the analysis and secondary domains were noted in result tables.

Level of evidence and quality assessment

The Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice Rating Scale (34) was used to determine the level of evidence and quality, where each article was assigned a level of evidence rating between I–III and quality evidence score from A–C. Level I articles are experimental studies, and randomized controlled trials (RCT). Level II articles are quasi-experimental studies, systematic review of a combination of RCTs and quasi-experimental studies with or without meta-analysis, and level III articles are qualitative studies or non-experimental study designs. High quality articles received an A rating and low-quality articles received a C rating. DT, ML, VS, JK, and BF rated the manuscripts independently and DT made the final decision on the evidence and quality ratings for all articles.

Results

Three hundred and forty-four articles met the criteria for full text review, and 19 were included in the synthesis. The studies focused on three out of the five SDOH domains including social and community context, healthcare access and quality, and economic stability. Tables 1,2 present patient, family caregiver, and study characteristics including level of quality for each article. Fifty-eight percent of articles in this review were assigned to the social and community context domain. The Social and Community Context domain is described as the psychosocial context of a community including social cohesion, community engagement, and social support that can determine an individual’s well-being (5,6). The health care access and quality domain involves the availability of health coverage and specialist healthcare providers, quality of care, and the cultural competency of healthcare providers (5). Thirty-two percent of articles in this review were assigned to the health care access and quality domain. The economic stability domain relates to factors such as income, employment, debt, and expenses, all of which can affect an individual’s health (5). Eleven percent of articles in this review were assigned to the economic stability domain. Most caregivers were White females but one article highlighted the experiences of African American/Black females (45) and two articles focused primarily on White male caregivers (37,46).

Table 1

| Primary author & year | Patient characteristics | Family caregiver characteristics | Study characteristics | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage of disease | Treatment type | Age, years (range or mean) | Sex or gender (majority) | Race/ethnicity | Study design | Sample size | Location | Evidence level & quality | |||

| Williams 2013 (35) | I, II, III | C | 18–84 | Female | AA/B, AA, W, O | Cohort | 84 | New Haven, CT | IIA | ||

| Grant 2013 (36) | I, II, III, IV | Otherc | 57 | Female | AA/B, AA, NA, H/L, PI, W | Cohort | 163 | Duarte, CA | IIIB | ||

| Litzelman 2016 (37) | I, II, III, IV | C, R, S | 20–71 | Male | W, O | Cross Sectional | 1,500 | Multiple | IIIA | ||

| Mosher 2013 (38) | Othera | C, R, S | 26–83 | Female | AA/B, W | Cross Sectional | 91 | Indianapolis, IN | IIB | ||

| Dionne-Odom 2018† (39) | IV | Otherc | 65.5 | Female | AA/B, W, O | Cross Sectional | 294 | Multiple | IIIB | ||

| Kramer 2011† (40) | I, II, III, IV | Otherc | 63 | Female | AA/B, W | Cross Sectional | 152 | WI (Statewide) | IIIB | ||

| Kramer 2010† (41) | Otherb | Otherc | 63 | Female | AA/B, W | Cross Sectional | 155 | WI (Statewide) | IIB | ||

| van Ryn 2011† (42) | I, II, III, IV | C, R, S | 21–80 | Female | AA/B, AA, H, NA, W | Cross Sectional | 335 | Multiple | IIA | ||

| Mazanec 2011 (43) | Othera | Otherc | 39 | Female | AA/B, W | Qualitative | 14 | Multiple | IIIC | ||

| Stone 2012¶ (44) | Othera | Otherc | 36–72 | Female | AA/B, AA, W, O | Qualitative | 35 | Chicago, IL | IIIB | ||

| McDonnell 2019 (45) | I, II, III | Otherc | 54 | Female | AA/B | Qualitative | 26 | Multiple | IIIA | ||

†, Health care access and quality; ¶, Neighborhood & built environment. aOther, stage of disease information not provided; bOther, deceased. cOther, treatment type information not provided. C, chemotherapy; R, radiation; S, surgery; W, White; AA/B, African American or Black; AA, Asian American; H/L, Hispanic/Latino; NA, Native American; PI, Pacific Islander including Hawaiian; O, Other groups.

Table 2

| Primary author & year | Patient characteristics | Family caregiver characteristics | Study characteristics | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage of disease | Treatment type | Age, years (range or mean) | Sex or gender (majority) | Race/ethnicity | Study design | Sample size | Location | Evidence level & quality | |||||

| Health care access and quality domain | |||||||||||||

| Litzelman 2016‡ (46) | I, II, III, IV | C, R, S | 20–71 | Male | W, O | Cross Sectional | 689 | Multiple | IIIB | ||||

| Martin 2012 (47) | I, II, III, IV | Otherb | Otherc | Female | AA/B, W | Cohort | 607 | Multiple | IIIA | ||||

| Mosher 2013‡ (48) | I, II, III, IV | C, R, S | 29–80 | Female | AA/B, W, O | Cross Sectional | 83 | Multiple | IIIB | ||||

| Mosher 2015‡ (49) | I, II, III, IV | C, R, S | 53 | Female | AA/B, W, O | Qualitative | 21 | New York, NY | IIIA | ||||

| Williams 2012‡ (50) | Othera | C | 52.3 | Female | AA/B, AA, W, O | Qualitative | 135 | New Haven, CT | IIIB | ||||

| Zhang 2012 (51) | II, III, IV | C, R, S | 49–57 | Female | AA/B, W | Cross Sectional | 199 | Cleveland, OH | IIA | ||||

| Economic stability domain | |||||||||||||

| Van Houtven 2010‡ (52) | I, II, III, IV | C, R, S | Otherc | Female | AA/B, H/L, W, O | Cross Sectional | 865 | Multiple | IIA | ||||

| Mosher 2013‡ (53) | I, II, III, IV | C, R, S | 29–80 | Female | AA/B, W, O | Cross Sectional | 83 | Multiple | IIB | ||||

‡, social and community context. aOther, stage of disease information not provided. bOther, treatment type information not provided. cOther, age range/mean information not provided. C, chemotherapy; R, radiation; S, surgery; W, White; AA/B, African American or Black; AA, Asian American; H/L, Hispanic/Latino; O, Other groups.

Evidence level and quality assessment

Overall, studies included in this review revealed variations in evidence levels and the quality of the assessments (see Tables 1,2). Most of the studies were rated as either “high quality” or “good quality” with 42% of the studies classified with an A-rating (“high quality”) and 53% of the studies classified with a B-rating (“good quality”). Only one study (5%) was assigned a C-rating, indicating a “low quality or major flaws” distinction. In terms of evidence levels, 63% of studies demonstrated level III evidence and 37% level II evidence.

Four general themes were observed across articles on the influence of SDOH on FCG-centered outcomes in lung cancer: (I) overall quality of life, (II) relationship quality including spirituality, (III) psychological well-being, and (IV) financial toxicity.

Theme 1: overall QOL of FCGs

Four papers focused on the overall QOL of FCGs, with two papers exploring the relationship of race with caregiving. It is well documented that FCGs provide significant clinical care including treatment related side effects management for newly diagnosed lung cancer patients without training (42). McDonnell and colleagues reported family members need basic education, skills training, and support related to the lung cancer diagnosis and other cancers (45). Current methods to provide these services are limited in their accessibility, availability, and effectiveness. FCGs contributions to improving the patients’ overall QOL are also often at the detriment of their own health, decreased economic mobility, and increased caregiving burden as they are also caring for other family members (36,42). In addition, racial disparities in the caregiving experience exist and despite greater preparedness for the caregiving role African American caregivers reported more weekly hours caregiving than whites (45,47). African American FCGs experience several stressors compounded with lack of access to resources (e.g., education, skills training) to support their caregiving roles (45). As discussed by Grant et al. (36) interventions to improve caregiver outcomes should include a holistic model of care that incorporates QOL domains (physical, psychological, social, spiritual well-being), addresses caregiver burden, provides skills training, and a self-care plan.

Theme 2: relationship quality

The role of a caregiver can impact an individual’s quality of relationships on multiple levels, including relationships with family, friends, healthcare providers, and a higher power expressed through their spiritual journeys. Nine papers discussed the role of relationship quality in the lives of family caregivers of lung cancer patients, with two papers further exploring relationships with spirituality. While many caregivers of patients with lung cancer experience negative physical and mental health effects, relations with family members improved for a substantial minority of caregivers (38,50). Williams et al. reported that some caregivers found positive outcomes from the overall cancer experience, such as the opportunity to prioritize and develop new relationships, collaborate as a family, and practice better communication (50). Conversely, Kramer et al. reported that family conflict was found to be higher in family dynamics with a history of prior conflict (40,41). In addition, Kramer et al. also reported caregivers of patients with greater physiological and clinical care needs, and shared decision-making challenges were more likely to have greater family conflict (41). Further, older age was associated with less social stress, and better family functioning, but worse relationship quality while caring for a female patient was associated with less social stress and better relationship quality, but worse family functioning (37). For some, understanding the child-parent relationship in the context of the illness balanced with the consideration of other family members’ perspectives and coping with the caregiving role posed additional relationship challenges (44). In addition to fostering relationships with family and friends, many caregivers turned to faith for comfort. Most caregivers found solace in religious practices, especially prayer (50). The strongest associations with low confidence in surrogate decision-making were low spiritual growth self-care and high use of avoidant coping (39). Moreover, Zhang et al. reported avoidant behavior demonstrated racial differences around end-of-life decision making, care and communication (51).

Theme 3: psychological well-being

Five articles describe the psychological well-being of caregiving with an emphasis on the negative health impact for FCGs due to various sociodemographic factors. As an important member of the treatment team, caregivers’ health and psychological well-being are often correlated with how patients with cancer perceive their care (46). For example, when caregivers reported fair or poor self-related health, patients were more than three times more likely to report fair or poor perceived quality of care. Distinct from the patient’s well-being, FCGs experience significant psychological stressors resulting in negative health outcomes related to several sociodemographic factors including ethnicity (35), education (35,48), stigma associated with mental health service use (49) and distance (43). Caregivers of patients receiving curative treatment (chemotherapy) have lower rates of depressive symptoms, but greater negative health impact related to the length of time in their caregiving role (median, 6.5 months) (35). Latino caregivers had significantly higher depressive symptoms than non-Latino caregivers, but additional research is warranted to understand the clinical significance of these findings with a larger sample. Caregivers with less than a college degree were more likely to have increased depressive symptoms indicating a mediating effect between lower socioeconomic status and negative psychological health outcomes. Greater levels of education (mean of 15 years) were also associated with the use of mental health services and complementary and alternative medicine methods to reduce caregiver burden (48). Additionally, Mosher and colleagues concluded caregivers perceived a conflict between mental health services use and the caregiving role (prioritizing the patients’ needs) (49). Although caregivers denied stigma associated with service use, their anticipated negative self-perceptions if they were to use services suggest that stigma may have influenced their decision to not seek services. Furthermore, Mazanec et al., denoted distance caregivers (individuals who reside 100 miles from patient) of lung cancer patients diagnosed with advance lung cancer experience similar stressors as local caregivers in addition to unique psychosocial stressors due to geographic distance (43).

Theme 4: financial toxicity

Two articles described the significant economic burden experienced by caregivers of lung cancer patients. Most FCGs of lung cancer patients experienced one or more adverse economic or social changes since the patient’s illness (52,53). Caregiving can be costly to family members in terms of both time and money (52). Caregivers often sacrifice both leisure time and time that could be spent working for pay. A substantial minority of caregivers lose their main source of family income or make a major change (e.g., delaying medical care for another family member) in family plans due to the cost of the illness (53). Other caregivers reported family members made major life changes (e.g., quit work) to care for the patient or their family lost most or all their savings since the patient’s illness (53). Van Houtven et al., concluded the loss of major source of family income was also associated with the patient’s receipt of surgery (52). Additionally, the economic burden was higher for caregivers of patients diagnosed at stage 4 versus stage 1; and spouses faced higher economic burden than other relatives or friends.

Discussion

This systematic literature review provides a broad overview of the relationship between SDOH and lung cancer outcomes for FCGs. While SDOH factors account for nearly 80% of an individual’s health status (31), researchers continue to focus largely on social and community context, health care access and quality, and economic stability domains (19). FCGs remain an understudied group in oncology research, although they often experience the burden of SDOH related health outcomes which in turn often leads to poor health and decreased QOL (54). While most studies on FCGs focused on social and community context, there were no studies on the effect of the neighborhood and built environment and minimal context on the role of educational access. The lack of attention on FCGs’ experiences within the health care system was disconcerting, considering the significant role of caregiving on QOL for this population (47-50). Future studies should explore the unmet needs of FCGs in navigating the health care system in relation to time spent caregiving, shared decision-making processes with providers, and the potential health implications for themselves.

The social and community context domain focused on QOL experiences of FCGs from a single time point, which minimizes generalizability. Moreover, we found increased psychosocial stressors due to several sociodemographic factors that are critical to understanding the social and environmental determinants of QOL outcomes for FCGs that are also understudied (35,43,46,48,49). While some patients are living longer because of screening and treatment advancements for lung cancer, the negative long-term effects of caregiving have not been studied extensively (55,56). For instance, FCGs who reported negative caregiving experiences reported worse physical and mental health effects 10 years after the patient’s initial diagnosis (55). Importantly, conclusions based on the current evidence are applicable to predominantly non-Hispanic White female FCGs. It’s critical to include underrepresented minorities and historically excluded groups in future research efforts as the patients and FCGs in these groups have the greatest cancer burden and lower QOL.

Spirituality has been shown to improve QOL for cancer patients and FCGs (57-59). Two studies included the observational (cohort and qualitative study designs) impact of spirituality on psychological well-being across multiple stages of the disease (39,50). FCGs used spirituality as a primary source of support to cope with treatment, survivorship, and end of life experiences. African American/Black female FCGs used faith as a primary source of social support (45). Spirituality has been shown to encourage social cohesion (28,29); and understanding its usage in intervention planning and development may improve QOL outcomes for FCGs.

Financial toxicity is also common among patients and FCGs during and after treatment; this in turn may impact access to care, clinical outcomes and QOL. FCGs experience considerable economic burdens related to their caregiving role (52,53); however, this area of study is under-developed and warrants additional research. Importantly, none of the studies in this review included research on neighborhood and built environment. The increased risk of environmental toxicants from residential (60-62) and occupational (63,64) settings and lung cancer diagnosis for patients are discussed in the literature. While evidence suggests that educational attainment equates to a healthier and longer life (4), and low attainment is associated with treatment delays, functional impairment and poor QOL in lung cancer patients (65-67), no articles focused on this domain for FCGs. Extensive variations in the measure of education in the field of social science exists, in that education can be measured by years of completion, highest education qualification, or highest degree achieved (68). Future research should consider selection of commonly used measures individually and combined when analyzing the impact of educational attainment on health outcomes for lung cancer patients and FCGs.

Validated instruments are critical to our understanding of education, spirituality and other SDOH factors on FCG centered outcomes. They also ensure researchers are measuring intended study variables, minimizing researcher bias and subjectivity (69). Demographic variables such as age, sex or gender, race/ethnicity, education level, marital status, employment status, income, and health insurance status were primarily used across the studies in this review to provide some context of the populations’ social position. This was expected, as efforts to standardize SDOH data collection tools and integration of these tools into primary care settings are recent (70). The field should move toward data collection strategies that include standardized tools such as the Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patients’ Assets, Risks, and Experiences (PRAPARE), Health Begins’ Upstream Risks Screening Tool, the Accountable Health Communities Health-related Social Needs Screening Tool or include tools from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) to provide critically needed information regarding social needs for lung cancer patients and their FCGs (Appendix 2). Further exploration of the unmet needs of FCGs across all SDOH domains using both qualitative (e.g., focus groups and key informant interviews) and quantitative approaches is clearly warranted.

Limitations and strengths

There are several limitations that should be considered in the interpretation of the results from this systematic literature review. Since we added a quality assessment component, the Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice Rating Scale (34), we were able to report the quality of studies and the level of evidence varied widely. As the research on SDOH continues to evolve, the field should also consider testing interventions that address SDOH needs of the most vulnerable populations. We also acknowledge that the process of assigning studies to their respective domains may not have been devoid of selection bias despite the considerable actions taken by the authors to reach consensus in appropriately assigning studies (4,71) including the engagement of subject matter experts. While not within the scope of this review, we acknowledge that racial/ethnic minorities especially African American/Black and Hispanic populations are disproportionally affected by this disease but are underrepresented in this already sparse SDOH FCG literature thus warranting additional research (72,73). Lastly, we also recognize research conducted outside the U.S. is important, but due to country-level differences in social and cancer care delivery structures, we chose to only focus on studies conducted in the U.S. as SDOH factors may differ across societal infrastructures.

Despite these limitations, there are also several strengths to note. To our knowledge this is the first review to classify studies by SDOH domains for lung cancer FCGs. Secondly, the authors included a deliberate discussion on the impact of spirituality on QOL—an understudied topic in SDOH research. Thirdly, we provide context on the dearth of research on lung cancer FCGs, and the critical need to better understand QOL outcomes in future SDOH studies. Fourthly, we excluded patients only and both patients and FCG articles across several locations (see Appendix 3) to provide specificity and useful information on the current state of the literature on the impact of SDOH domains on FCG-centered outcomes in lung cancer. Finally, we bring attention to the lack of validated SDOH instruments used and provide examples of tools and resources that researchers could consider adopting to promote better measurement uniformity in SDOH research (Appendix 2).

Conclusions

There is a lack of knowledge on SDOH domains such as education quality and access, and neighborhood and built environment for FCGs. Spirituality, while important in improving QOL of FCGs, remains an underdeveloped field of study. The increased integration of validated SDOH tools in research is critical to further our understanding of QOL outcomes for lung cancer patients and their FCGs.

Acknowledgments

We thank Andrea Lynch, MLIS for her assistance with the literature search.

Funding: This systematic review was supported by award number 3R01CA217841-03S1 from the National Cancer Institute, National Institute of Health.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the PRISMA reporting checklist. Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-22-1613/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-22-1613/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-22-1613/coif). LE reports payments from Lung Cancer Research Foundation and American Association of Thoracic Surgery. LE is a member of the scientific advisory board of Lung Cancer Research Foundation. LE sat on the health disparities advisory board of AstraZeneca in 2021. LE reports payments from AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals for giving a presentation to the organization on Barriers to Lung Cancer Research (LCS) in July 2022. LE also reports payment from Gilead Oncology for giving a health equity presentation to the organization in March 2022. VS reports grants from National Cancer Institute and Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, et al. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin 2022;72:7-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhu S, Yang C, Li J, et al. Mediating factors between caregiver burden and quality of life in caregivers of older patients with newly diagnosed lung cancer. Age & Ageing 2021;50:i12-42. [Crossref]

- Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, et al. Integration of Palliative Care Into Standard Oncology Care: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:96-112. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Social determinants of health 2020. Available online: https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives

- Asare M, Flannery M, Kamen C. Social Determinants of Health: A Framework for Studying Cancer Health Disparities and Minority Participation in Research. Oncol Nurs Forum 2017;44:20-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Social determinants of health 2019. Available online: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health.

- Braveman P, Gottlieb L. The social determinants of health: it's time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep 2014;129:19-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cockerham WC, Hamby BW, Oates GR. The Social Determinants of Chronic Disease. Am J Prev Med 2017;52:S5-S12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kawakami N, Li X, Sundquist K. Health-promoting and health-damaging neighbourhood resources and coronary heart disease: a follow-up study of 2 165 000 people. J Epidemiol Community Health 2011;65:866-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Major JM, Doubeni CA, Freedman ND, et al. Neighborhood socioeconomic deprivation and mortality: NIH-AARP diet and health study. PLoS One 2010;5:e15538. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro AI, Amaro J, Lisi C, et al. Neighborhood Socioeconomic Deprivation and Allostatic Load: A Scoping Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15:1092. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hystad P, Carpiano RM, Demers PA, et al. Neighbourhood socioeconomic status and individual lung cancer risk: evaluating long-term exposure measures and mediating mechanisms. Soc Sci Med 2013;97:95-103. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Meijer M, Bloomfield K, Engholm G. Neighbourhoods matter too: the association between neighbourhood socioeconomic position, population density and breast, prostate and lung cancer incidence in Denmark between 2004 and 2008. J Epidemiol Community Health 2013;67:6-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Erhunmwunsee L, Joshi MB, Conlon DH, et al. Neighborhood-level socioeconomic determinants impact outcomes in nonsmall cell lung cancer patients in the Southeastern United States. Cancer 2012;118:5117-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Galea S, Tracy M, Hoggatt KJ, et al. Estimated deaths attributable to social factors in the United States. Am J Public Health 2011;101:1456-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goding Sauer A, Siegel RL, Jemal A, et al. Current Prevalence of Major Cancer Risk Factors and Screening Test Use in the United States: Disparities by Education and Race/Ethnicity. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2019;28:629-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abrams HR, Durbin S, Huang CX, et al. Financial toxicity in cancer care: origins, impact, and solutions. Transl Behav Med 2021;11:2043-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann C, Burman D, Swami N, et al. Determinants of quality of life in patients with advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer 2011;19:621-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morone J. An Integrative Review of Social Determinants of Health Assessment and Screening Tools Used in Pediatrics. J Pediatr Nurs 2017;37:22-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gottlieb L, Hessler D, Long D, et al. A randomized trial on screening for social determinants of health: the iScreen study. Pediatrics 2014;134:e1611-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Garg A, Toy S, Tripodis Y, et al. Addressing social determinants of health at well child care visits: a cluster RCT. Pediatrics 2015;135:e296-304. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Walker RJ, Smalls BL, Campbell JA, et al. Impact of social determinants of health on outcomes for type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Endocrine 2014;47:29-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cohen AK, Rai M, Rehkopf DH, et al. Educational attainment and obesity: a systematic review. Obes Rev 2013;14:989-1005. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moore C, Hassett D, Dunne S. Health literacy in cancer caregivers: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv 2021;15:825-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Puchalski C, Ferrell B, Virani R, et al. Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: the report of the Consensus Conference. J Palliat Med 2009;12:885-904. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fisher J. The four domains model: Connecting spirituality, health and well-being. Religions 2011;2:17-28. [Crossref]

- National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. National Consensus Project Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Care. 2018.

- Kawachi I, Berkman L. Social cohesion, social capital, and health. Social Epidemiology 2000;174(7).

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Social cohesion 2019. Available online: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-health/interventions-resources/social-cohesion#6.

- Sidorchuk A, Agardh EE, Aremu O, et al. Socioeconomic differences in lung cancer incidence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Causes Control 2009;20:459-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- The National Conference of State Legislatures. Racial and ethnic health disparities: What state legislators need to know 2013.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372: [PubMed]

- Babineau J. Product review: covidence (systematic review software). Journal of the Canadian Health Libraries Association 2014;35:68-71. [Crossref]

- Newhouse R, Dearholt S, Poe S, Pugh L, White K. The Johns Hopkins nursing evidence-based practice rating scale. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins Hospital. 2005.

- Williams AL, Tisch AJ, Dixon J, et al. Factors associated with depressive symptoms in cancer family caregivers of patients receiving chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer 2013;21:2387-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grant M, Sun V, Fujinami R, et al. Family caregiver burden/skills preparedness, and quality of life in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum 2013;40:337-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Litzelman K, Kent EE, Rowland JH. Social factors in informal cancer caregivers: The interrelationships among social stressors, relationship quality, and family functioning in the CanCORS data set. Cancer 2016;122:278-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mosher CE, Bakas T, Champion VL. Physical health, mental health, and life changes among family caregivers of patients with lung cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 2013;40:53-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dionne-Odom JN, Ejem D, Azuero A, et al. Factors Associated with Family Caregivers' Confidence in Future Surrogate Decision Making for Persons with Cancer. J Palliat Med 2018;21:1705-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kramer BJ, Kavanaugh M, Trentham-Dietz A, et al. Complicated grief symptoms in caregivers of persons with lung cancer: the role of family conflict, intrapsychic strains, and hospice utilization. Omega (Westport) 2010-2011;62:201-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kramer BJ, Kavanaugh M, Trentham-Dietz A, et al. Predictors of family conflict at the end of life: the experience of spouses and adult children of persons with lung cancer. Gerontologist 2010;50:215-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van Ryn M, Sanders S, Kahn K, et al. Objective burden, resources, and other stressors among informal cancer caregivers: a hidden quality issue? Psychooncology 2011;20:44-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mazanec P, Daly BJ, Ferrell BR, et al. Lack of communication and control: experiences of distance caregivers of parents with advanced cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 2011;38:307-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stone AM, Mikucki-Enyart S, Middleton A, et al. Caring for a Parent with Lung Cancer: Caregivers’ Perspectives on the Role of Communication. Qualitative Health Research 2012;22:957-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McDonnell KK, Owens OL, Hilfinger Messias DK, et al. Health behavior changes in African American family members facing lung cancer: Tensions and compromises. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2019;38:57-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Litzelman K, Kent EE, Mollica M, et al. How Does Caregiver Well-Being Relate to Perceived Quality of Care in Patients With Cancer? Exploring Associations and Pathways. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:3554-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Martin MY, Sanders S, Griffin JM, et al. Racial variation in the cancer caregiving experience: a multisite study of colorectal and lung cancer caregivers. Cancer Nurs 2012;35:249-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mosher CE, Champion VL, Hanna N, et al. Support service use and interest in support services among distressed family caregivers of lung cancer patients. Psychooncology 2013;22:1549-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mosher CE, Given BA, Ostroff JS. Barriers to mental health service use among distressed family caregivers of lung cancer patients. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2015;24:50-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Williams AL, Bakitas M. Cancer family caregivers: a new direction for interventions. J Palliat Med 2012;15:775-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang AY, Zyzanski SJ, Siminoff LA. Ethnic differences in the caregiver's attitudes and preferences about the treatment and care of advanced lung cancer patients. Psychooncology 2012;21:1250-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Van Houtven CH, Ramsey SD, Hornbrook MC, et al. Economic burden for informal caregivers of lung and colorectal cancer patients. Oncologist 2010;15:883-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mosher CE, Champion VL, Azzoli CG, et al. Economic and social changes among distressed family caregivers of lung cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2013;21:819-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Möllerberg ML, Sandgren A, Lithman T, et al. The effects of a cancer diagnosis on the health of a patient's partner: a population-based registry study of cancer in Sweden. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2016;25:744-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Best AL, Shukla R, Adamu AM, et al. Impact of caregivers’ negative response to cancer on long-term survivors’ quality of life. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2021;29:679-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yeung NCY, Ramirez J, Lu Q. Perceived stress as a mediator between social constraints and sleep quality among Chinese American breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 2017;25:2249-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lalani N, Duggleby W, Olson J. Spirituality among family caregivers in palliative care: an integrative literature review. Int J Palliat Nurs 2018;24:80-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jimenez-Fonseca P, Lorenzo-Seva U, Ferrando PJ, et al. The mediating role of spirituality (meaning, peace, faith) between psychological distress and mental adjustment in cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2018;26:1411-8. [PubMed]

- Best AL, Alcaraz KI, McQueen A, et al. Examining the mediating role of cancer-related problems on spirituality and self-rated health among African American cancer survivors: a report from the American Cancer Society's Studies of Cancer Survivors-II. Psycho-Oncology 2015;24:1051-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Torres-Durán M, Ruano-Ravina A, Kelsey KT, et al. Small cell lung cancer in never-smokers. Eur Respir J 2016;47:947-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Martínez Á, Ruano-Ravina A, Torres-Durán M, et al. Small Cell Lung Cancer. Methodology and Preliminary Results of the SMALL CELL Study. Arch Bronconeumol 2017;53:675-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Torres-Durán M, Ruano-Ravina A, Parente-Lamelas I, et al. Residential radon and lung cancer characteristics in never smokers. Int J Radiat Biol 2015;91:605-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Consonni D, De Matteis S, Pesatori AC, et al. Lung cancer risk among bricklayers in a pooled analysis of case-control studies. Int J Cancer 2015;136:360-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bracci PM, Sison J, Hansen H, et al. Cigarette smoking associated with lung adenocarcinoma in situ in a large case-control study (SFBALCS). J Thorac Oncol 2012;7:1352-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nipp RD, Fuchs G, El-Jawahri A, et al. Sarcopenia Is Associated with Quality of Life and Depression in Patients with Advanced Cancer. Oncologist 2018;23:97-104. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Billmeier SE, Ayanian JZ, He Y, et al. Predictors of nursing home admission, severe functional impairment, or death one year after surgery for non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Surg 2013;257:555-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Verma R, Pathmanathan S, Otty ZA, et al. Delays in lung cancer management pathways between rural and urban patients in North Queensland: a mixed methods study. Intern Med J 2018;48:1228-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Connelly R, Gayle V, Lambert PS. A review of educational attainment measures for social survey research. Methodological Innovations 2016;9:2059799116638001. [Crossref]

- Solans-Domènech M, Pons JMV, Adam P, et al. Development and validation of a questionnaire to measure research impact. Research Evaluation 2019;28:253-62. [Crossref]

- LaForge K, Gold R, Cottrell E, et al. How 6 Organizations Developed Tools and Processes for Social Determinants of Health Screening in Primary Care: An Overview. J Ambul Care Manage 2018;41:2-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Artiga S, Hinton E. Determinants in Promoting Health and Health Equity. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2018 May 10.

- Schabath MB, Cress D, Munoz-Antonia T. Racial and Ethnic Differences in the Epidemiology and Genomics of Lung Cancer. Cancer Control 2016;23:338-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ryan BM. Lung cancer health disparities. Carcinogenesis 2018;39:741-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]