Application of the Montgomery T-tube in subglottic tracheal benign stenosis

Introduction

Subglottic tracheal benign stenosis (STBS) refers to subglottic airway narrowing caused by damage to the normal tracheal wall structure by non-neoplastic diseases, leading to symptoms such as coughing, sputum, and breathing difficulty. Airway stenosis occurs in the upper trachea below the glottis, severely affecting the patient’s quality of life and occasionally resulting in death due to respiratory failure. STBS is mainly caused by long-term tracheal intubation, tracheotomy, tracheobronchial tuberculosis, trauma, infection, congenital malformations, or inflammatory lesions. With improved surgical techniques, the incidence of secondary benign airway stenosis caused by tracheal intubation and tracheotomy is increasing, as is the incidence of STBS. Among critical patients on intensive care unit (ICU) mechanical ventilation, the incidence of tracheal benign stenosis is reported to be approximately 1% (1). STBS manifestations are complex. Radical surgical resection and reconstruction is an important approach to treating such diseases (2), but whether the surgery should be performed depends on many factors such as the degree and range of airway stenosis and co-infections. In addition, the surgery has high requirements for the patient’s basic physical conditions, often combined with many perioperative complications and a high incidence of long-term anastomotic restenosis (3). Shortcomings such as long recovery times after surgery, especially in patients with complications such as lung infections and central nervous system dysfunction, often make these patients unable to tolerate traditional surgery. Palliative tracheotomy greatly influences patients’ quality of life; therefore, treatment choices should be balanced among conservative treatment, interventional therapy, and surgery, relying on close collaboration and consultation with physicians from multiple disciplines while considering the patient’s needs and wishes. With bronchoscopic interventions trending, increasing endoscopic interventional treatments (e.g., laser therapy, balloon dilation, cryotherapy, stent implantation, etc.) have been developed, providing safer and more effective treatment options for patients with STBS after tracheotomies. Of these, the Montgomery T-tube (referred to as the T-tube hereafter) is a rigid bronchoscopic insertion considered to be relatively safe, effective, and well-tolerated due to its minimal trauma, easy operation, and rapid symptomatic relief for the patient.

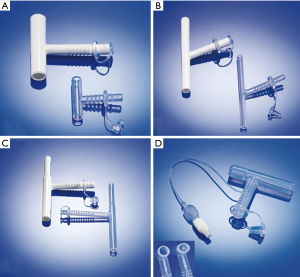

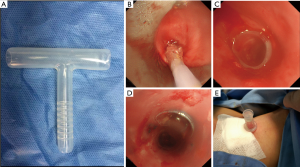

The T-tube was first invented in 1962 by William Montgomery, a physician at Harvard Medical School and the Department of Otorhinolaryngology of Massachusetts General Hospital. The T-tube was first applied to prevent tracheal stenosis after tracheal surgery (4). Initially, the T-tube used acrylic material, which was too rigid to intubate and severely affected the expectoration function of tracheal cilia. In 1986, Boston Medical Products developed the “safe-T-tube” and later used an implantable silicone material (5). In its early days, the T-tube was mainly applied to treat acute tracheal injuries and stenosis and in temporary preoperative preparation for tracheal reconstruction or tracheotomy and anastomosis. It was also used for patients with laryngotracheal stenosis unsuitable for surgical treatment and in transitionally treating benign tracheal lesions before surgery (6). Compared with other tracheal stent designs, the T-tube’s design features are as follows. (I) T-tubes have smooth inner and outer walls and maximally retain the mucociliary expectoration function compared with metallic coated stents, which are more inclined to cause secretions to accumulate and clog. This is unavoidable and causes the stent to be removed in some cases. Moreover, the T-tube surface is highly polished, so scabbing and adhesion are prevented, and the cone-shaped connection on the edge provides comfort while preventing granulation tissue hyperplasia. (II) The T-tube’s internal branch is used to support and shape the trachea, and the external branch is used to fasten the T-tube, which overcomes the high displacement tendency of the commonly used straight silicone stent. Stent displacement is reported to occur in 6–18% of the patients who are inserted with straight silicone DUMON stents (7,8). Moreover, the ring and groove design of the external branch enables fixing the spacer and utterance valve, which prevents the T-tube’s displacement when the patient breathes or talks. (III) The T-tube’s internal branch has different models with varying diameters, offering options to patients with different tracheal thicknesses. The operating physician can determine the upper and lower branch lengths based on the length of stenotic tracheal section and the tracheostomy site, which requires careful and accurate measurement and evaluation before placing the T-tube. (IV) In addition to the standard model, other models include the children’s model with a conical design in the upper branch and the Hebeler model, which includes a balloon (Figure 1) to meet different needs. (V) In cases of stenosis in the upper T-tube or a secretion clog inside the T-tube, the external branch can be opened, and ventilation and sputum aspiration can be safely performed externally or through the ventilator. (VI) Placing and removing the T-tube are simple and safe (9), and after placement, the patient can resume natural breathing and talking. In summary, compared with the conventional self-expanding metal stents and straight silicone DUMON stents, the Montgomery T-tube is a better choice for STBS.

T-tube choice and preoperative preparation

Preoperative evaluation is the key to successfully placing the T-tube, as it is necessary to clarify contraindications and understand the nature of the lesion as well as the treatment strategy being adopted.

Contraindications

First, when implanting a T-tube, using a rigid bronchoscope is required, so contraindications related to its operating should be included on the list of contraindications for patients treated with T-tubes including (10) (I) restrained head and neck movements: head and neck malformations, neck fixation (cervical myelopathy), etc., and (II) restrained mouth opening: maxillofacial trauma, facial burns, oral deformities, etc. Second, because the surgery must be performed under general anesthesia, contraindications related to general anesthesia must be checked.

Successful

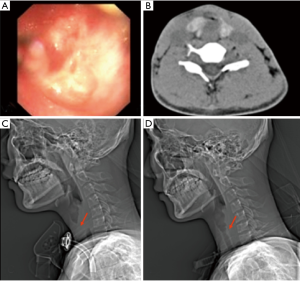

T-tube placement is closely related to stenosis location and length. Therefore, preoperatively, the extent and severity of airway stenosis, and the distances of the stenosis from the glottis and carina must be fully assessed via imaging examinations. A CT scan of the neck and thorax should also be performed, and tracheal 3D reconstruction should be conducted if the condition permits to measure the extent of the tracheal lesion from the coronal, sagittal and axial perspectives, the extent and length of the tracheal stenosis, and the inspiratory tracheal diameter. T-tube specifications are determined by combining the preoperative or intraoperative bronchoscopy. This ensures that the upper branch of the T-tube is not too long or exceeds the glottis, otherwise it is prone to causing glottis discomfort and dysfunction, so the advantages and disadvantages should be considered for patients with a documented history of aspiration (11). The upper end of the T-tube should be at least 0.5–1 cm away from the glottis; thus, patients whose stenotic section is <2 cm from the glottis are unsuitable for T-tube insertion (12,13). The T-tube diameter should not be too thick or too tight and should be smaller than the airway diameter. Generally, a T-tube with a diameter of 11–14 mm is chosen, and a T-tube with a diameter that is too large increases the risk of granulation tissue hyperplasia on the edge of the T-tube, and compression and ischemia of the tracheal mucosa are prone to causing infection and restenosis, while a T-tube with too small a diameter may lead to sputum clogging, which is not conducive to airway (3). The supraglottic, vocal cord, and subglottic regions should be examined via laryngoscopy under local anesthesia. The possibility of postoperatively blocking the external T-tube branch can be significantly reduced in patients with supraglottic stenosis.

T-tube implanting operation: T-tube implantation approach

Anesthesia and ventilation

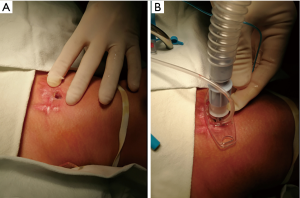

T-tubes are inserted under general anesthesia, which is more conducive to operating (14,15). Before inserting the T-tube, a tracheostomy tube must be inserted first to ensure ventilation and safe operation (Figure 2). After inserting a rigid bronchoscope, a high-frequency jet ventilator can be connected.

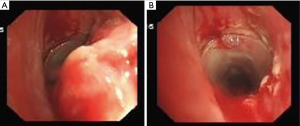

Airway stenosis intervention prior to T-tube placement

STBS patients may have different airway stenoses, such as cicatricial stenosis, granulation, tracheomalacia collapse, or complete or partial occlusion; thus, the airway must be treated before inserting the T-tube. After inserting the rigid bronchoscope, the stenotic lesions at the glottis and airway should be examined. For patients with incomplete airway obstruction, interventions such as mechanical expansion through the rigid bronchoscope, balloon dilatation, and granulation tissue resection can be performed to expand the narrow airway 10–15 mm to ensure adequate airway space for T-tube placement. For patients with complete airway obstruction, retrograde probing with surgical assistance is often needed from the distal end of the blocked trachea (Figure 3). After clarifying the anatomy, the blocked tracheal airway is recanalized from the proximal end using an electrosurgical generator or laser, and the narrow trachea is then expanded after successful recanalization (16), thus ensuring space for subsequent T-tube placement (Figure 4).

T-tube insertion approach

The T-tube can be inserted several ways, and below, we briefly present three common approaches.

Montgomery (4) described a classical insertion technique, in which the distal end of the T-tube is first inserted into the trachea using a hemostat, and the proximal end of the T-tube is oriented to the trachea using the hemostat until the entire internal branch of the tube enters the trachea. The T-tube’s proximal end is then positioned using the hemostat through a rigid bronchoscope. Because it is impossible to maintain ventilation during the insertion, the operation can become dangerous if it takes too long, especially for patients with significant stenosis on the upper tracheostomy stoma or a thick neck, posing a challenge to the operator.

In this approach, a rigid bronchoscope is first inserted while the patient is under general anesthesia. An umbilical string is inserted through the external branch of the T-tube and pulled out from the proximal end, and the string at the proximal end of the T-tube is pulled out through the tracheostomy stoma in the mouth through a rigid bronchoscope. The distal branch of the T-tube is positioned to the distal end of the trachea using a hemostat. After the distal branch is positioned, the string is straightened, and pulled upward through the bronchoscope to automatically advance the T-tube’s proximal end to the trachea’s proximal end (17). The main advantage of this technique is that the T-tube is pulled into the trachea to avoid blindly inserting the tube. This procedure is simple, safe, and widely used.

Some operators have improved on these two widely accepted T-tube insertion methods to ensure the patient is ventilated safely during the operation. In one case (18), the classical technique described by Montgomery was modified by introducing a small tracheal catheter through the external T-tube branch to the distal branch to maintain ventilation throughout the entire insertion process. In the other case (19), a cuffed tracheal catheter is connected to a tracheal catheter of the same diameter to form a long thin tracheal catheter that can be readily passed through the tracheostomy stoma. The catheter tip is inserted into the proximal branch of the T-tube, and the catheter cuff is then inflated with air, so the two catheters remain tightly connected. The T-tube’s distal branch is inserted into the trachea through the tracheostomy stoma, and at this time, while blocking the external T-tube branch, the patient is ventilated through the tracheal catheter. With the joint movement and extubation, the distal branch of the T-tube slides smoothly into the desired position.

Postoperative complications and treatment

Early complications

Early complications are mainly associated with surgery (20) and include postoperative fever, bleeding, mucus secretion, irritating coughing, short-term difficulty in breathing, etc., which can generally be alleviated by the symptoms.

Long-term complications

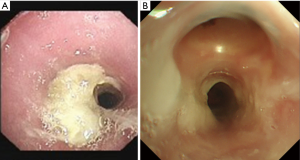

Long-term complications are mainly granulation tissue hyperplasia at the T-tube edge (Figure 4), T-tube blockage caused by expectoration difficulties (Figure 5) and secondary infection. The granulation tissue hyperplasia at the T-tube edge mainly occurs at the upper edge, likely caused by T-tube displacement resulting from the patient’s swallowing or talking (21), leading to excessive friction between the T-tube and luminal mucosa and stimulating granulation tissue proliferation. In addition, too short a distance between the upper end of the T-tube and the glottis may be a factor. Postoperatively, the patient’s expectoration ability should be closely monitored and evaluated, and the airway should be moistened daily. The patient should be encouraged to drink water frequently to promote expectoration, and the utterance valve should be mostly closed to prevent luminal dryness and dry sputum (Figure 6). If necessary, dry sputum should be periodically cleaned off the tube wall to prevent it from clogging. Patients should be encouraged to self-expectorate, so they are well prepared for subsequent extubation.

Extubation

For benign airway stenosis, the T-tube indwelling time is disputable (22), and the extubation timing should be determined by the patient’s circumstance. After inserting the T-tube, extubation is assessed based on the patient’s condition, postoperative coughing, expectoration training, and endoscopic examination. Cooper et al. (17) recommended 6–12 months of indwelling, while Martinez-Ballarin et al. (8) recommended 18 months. Carretta et al. (11) suggested that after 9–12 months of T-tube indwelling, the patient’s condition should be evaluated to determine whether the T-tube is ready to be extubated or replaced. However, many patients reportedly manifest no complications or intolerance, even with long-term T-tube intubation. Extubating the T-tube is simple and performed under general anesthesia by slowly pulling the side branch to extract the T-tube from the trachea, or by first cutting out the external branch and removing the internal portion with forceps under a rigid bronchoscope. After extubation, the airway condition must be closely monitored, and in cases of luminal stenosis, mucosal membrane congestion, edema, or excessive secretions, a temporary tracheostomy catheter should be placed to ensure safe ventilation. Some reported (22) that after T-tube extubation, a temporary tracheostomy catheter should be inserted, and after a 2-month follow-up, patients should be completely extubated if airway collapse or obstruction do not occur. Otherwise, the T-tube must be reinstalled, or surgery must be performed.

Conclusions

STBS incidence is increasing annually, seriously threatening the lives of patients and affecting their quality of life. For patients who are unsuited for surgical tracheal intubation or those with post-tracheostomy secondary SBTS, rigid bronchoscopic intubation with a Montgomery T-tube is an effective, safe, and well-tolerated trachea-forming method that helps to remodel the stenotic airway and significantly improve the patient’s quality of life. When treating SBTS with a T-tube, clinicians should fully understand the indications, contraindications, and complications of the T-tube and of rigid bronchoscopy and adopt corresponding treatments to achieve satisfactory outcomes.

Acknowledgements

Funding: The study was supported by Zhejiang Medical and Health Science and Technology Project (no. 2016ZDA010).

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Miñambres E, Burón J, Ballesteros MA, et al. Tracheal rupture after endotracheal intubation: a literature systematic review. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2009;35:1056-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grillo HC, Donahue DM, Mathisen DJ, et al. Postintubation tracheal stenosis. Treatment and results. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1995;109:486-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abbasidezfouli A, Shadmehr MB, Arab M, et al. Postintubation multisegmental tracheal stenosis: treatment and results. Ann Thorac Surg 2007;84:211-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Montgomery WW. T-tube tracheal stent. Arch. Otolaryngol 1965;82:320-1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Saghebi SR, Zangi M, Tajali T, et al. The role of T-tubes in the management of airway stenosis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2013;43:934-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Prasanna Kumar S, Ravikumar A, Senthil K, et al. Role of Montgomery T-tube stent for laryngotracheal stenosis. Auris Nasus Larynx 2014;41:195-200. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mitsuoka M, Sakuragi T, Itoh T. Clinical benefits and complications of Dumon stent insertion for the treatment of severe central airway stenosis or airway fistula. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2007;55:275-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Ballarin JI, Diaz-Jimenez JP, Castro MJ, et al. Silicone stents in the management of benign tracheobronchial stenosis. Tolerance and early results in 63 patients. Chest 1996;109:626-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Puma F, Farabi R, Urbani M, et al. Long-term safety and tolerance of silicone and self-expandable airway stents: an experimental study. Ann Thorac Surg 2000;69:1030-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lukomsky GI, Ovchinnikov AA, Bilal A. Complications of bronchoscopy: comparison of rigid bronchoscopy under general anesthesia and flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy under topical anesthesia. Chest 1981;79:316-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carretta A, Casiraghi M, Melloni G, et al. Montgomery T-tube placement in the treatment of benign tracheal lesions. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2009;36:352-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu HC, Lee KS, Huang CJ, et al. Silicon T-tube for complex laryngotracheal problems. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2002;21:326-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ko PJ, Liu CY, Wu YC, et al. Granulation formation following tracheal stenosis stenting: influence of stent position. Laryngoscope 2009;119:2331-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Choi BR, Chung JY, Yi JW, et al. The use of the Montgomery T-tube in postprocedural subglottic stenosis repair. Korean J Anesthesiol 2009;56:446-8. [Crossref]

- Wu CY, Liu YH, Hsieh MJ, et al. Airway stents in management of tracheal stenosis: have we improved? ANZ J Surg 2007;77:27-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu FJ, Hu HH, Hu SH, et al. Application of T-tube placement in treating post-tracheotomy tracheal stenosis after two-way airway recanalization. Chin J Tuberc Res Dis 2017;40:477-9.

- Cooper JD, Pearson FG, Patterson GA. Ann Thorac Surg 1989;47:371-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim KT, Sun K, Shin JS, et al. A simple and secure technique for tracheal T-tube insertion. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2001;20:1037-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bibas BJ, Bibas RA. A new technique for T-tube insertion in tracheal stenosis located above the tracheal stoma. Ann Thorac Surg 2005;80:2387-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Noirez L, Musani AI, Laroumagne S. J Bmnehology Interv Pulmonol 2015;22:e14-5. [Crossref]

- Stern Y, Willging JP, Cotton RT. Use of Montgomery T-tube in laryngotracheal reconstruction in children: is it safe? Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1998;107:1006-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li ZG, Li Q, Zhou WZ, et al. Treatment of subglottic benign tracheal stenosis with Montgomery T tube under rigid bronchoscope. Chin J Tuberc Res Dis 2014;37:308-9.